Mr.

Hideyuki Ban of CNIC has served as a member of the Nuclear Power

Subcommittee of the Electricity and Gas Industry Committee under the

Advisory Committee for Natural Resources and Energy since June 2014. He

is participating in the discussions from the standpoint of a phaseout

of nuclear power, supporters of which are a small minority in the

subcommittee. This article is one in a series of reports on the work of

the subcommittee as seen through his eyes.

The

question of a video

of the deliberations not being made public, as reported in Nuke Info

Tokyo 162, has still not been resolved. The current situation is that

poor quality audio recording of the proceedings will be made

available on the Internet up to the time when the minutes of the

meetings are published. An audio live Internet broadcast is also

not provided.

In addition, discussions

in the Radioactive Wastes Working Group, on which Mr. Ban also serves

as a member, restarted on October 23 after deliberations ended

following the publication of an interim report in May.1)

This report covers deliberations in the Nuclear Power Subcommittee up to the seventh meeting.

The third meeting (July 23) heard reports from the power companies and

the host municipalities on the moves toward a reduction of dependence

on nuclear power. The fourth meeting (August 7) concerned the

maintenance of nuclear power engineers and other human resources (but

this will not be dealt with in this report). The fifth meeting (August

21) discussed maintenance of the nuclear power business (nuclear power

plants and the nuclear fuel cycle) under power industry deregulation,

which was continued in the sixth meeting (September 16). The topic of

the seventh meeting (October 2) was contributions toward the global

peaceful use of nuclear power.

Policies to support nuclear power under power industry deregulation

Up to now, Japanese consumers have been unable to choose the power

company from which they purchase their power. The system has been that,

except for large-scale customers of 50 kW and over, if you live in

Tokyo then you have no option but to contract with the Tokyo Electric

Power Company (TEPCO) for power, and if you live in Osaka then you are

forced to contract with Kansai Electric Power Company (KEPCO).

One of the election pledges of the Abe administration was the bold

implementation of power system reform. A bill on the total deregulation

of the power industry (making it possible for ordinary consumers to

contract with any power company they like) was passed into law by the

Diet, and deregulation will be implemented from 2016. A bill separating

the power generation and power transmission sectors of each of the

power companies is also scheduled to be submitted to the regular

session of the Diet in 2015, with implementation planned for 2020. It

is anticipated that these laws will help make cheap power available and

give impetus to renewable energy, which has greater support among

citizens.

The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry has always claimed that

nuclear power is cheap, but the subcommittee, while tacitly recognizing

that nuclear power will be weeded out under deregulation due to its

higher costs, is considering what the government can do to ensure the

continuing existence of nuclear power plants.

In order to continue to use nuclear power plants, it is necessary to

rebuild (replace) power plants or construct new ones. However, the cost

of building a nuclear reactor is enormous, at about 400 billion yen

each, and it is said that a competitive environment would make

investment in new reactor construction impossible. The power companies

say that they are prepared to “promote the nuclear power generation

business as private business and restructure the safe and stable supply

of Japan’s energy and the security framework” (Hideki Toyomatsu,

subcommittee's expert member, Kansai Electric Power Company), but are

demanding that the government provide institutional support to back up

this preparedness.

An example cited was the case of the Contract for Difference (CfD), now

being considered in the UK as a means to ensure the establishment of an

environment for the replacement or new construction of nuclear reactors.

2)

The

examples of loan guarantees for advanced nuclear power plants and

guarantees against construction delays for new nuclear power plant

construction that have been introduced by the US government were also

discussed. While there was no clear indication of the introduction of

such a system into Japan, it seemed that consideration was being given

to some kind of similar support measures. Even if such support measures

are introduced, citizens living close to NPSs or where they are planned

are strengthening their opposition to NPSs more than ever before. For

example, all the city assemblies around the Sendai NPS have decided

against the proposed new Unit 3 there.

At the same time, the subcommittee envisaged that the huge investments

made necessary by the strengthening of safety standards would lead to

the decommissioning of some nuclear power plants. It is possible that

some nuclear power plants that have not yet been operable for 40 years

will remain shut down. If these are decommissioned, the remaining fixed

assets would be instantly written off, resulting in large financial

losses. Examples of special measures in other countries were given as

means to avoid this. The background to these arguments is that the

government wishes to encourage the decommissioning of obsolescent

nuclear power plants in order to reduce dependence on nuclear power.

Rethinking the cost of nuclear power plants

One of the reasons why the introduction of a concrete system has not

come into view is the issue of the cost of power generation. The media

is reporting that the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI)

has begun estimations of power generation cost by different power

sources. It seems that METI will review the calculations it made in

2011. According to the estimations at that time, the cost of generation

by nuclear power was assessed at “from 8.9 yen/kWh”. For this, damages

due to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station accident were

calculated to be 5.8 trillion yen. There is still no final settlement

for the total damages from the Fukushima nuclear accident, but since

the generation cost rises 0.1 yen for each trillion yen increase in

damages, the generation cost is assessed with the prefix “from”.

3)

Assessing the cost of power generation by nuclear power over a range is

based on the fact that the Atomic Energy Damage Compensation Act

(AEDCA) imposes unlimited liability for the accident on the power

company. Nevertheless, after the Fukushima accident had actually

occurred, new mechanisms were brought into play to avoid the collapse

of TEPCO. It appears that the government is now thinking along the

lines of a negative reform in which unlimited liability becomes limited

liability. In the case of limited liability, only a limited sum of

money is included in the generation cost of nuclear power, resulting in

a change in the direction of reducing the cost of nuclear power

generation.

If

the cost estimation includes the cheaper cost of new NPSs which meet

the new regulation, it would not be necessary to introduce a new

support system such as CfD.

Nationalization of reprocessing?

As it is government policy to maintain the nuclear fuel cycle, a

proposal was submitted to the 5th and 6th meetings to strengthen

government involvement in the trouble-ridden Rokkasho reprocessing

plant, which is still unable to function fully as expected, and to

support it by turning the facility into a government-approved

corporation. Some committee members voiced the opinion that the

reprocessing plant should be nationalized, but METI suggested the

policy of not nationalizing the facility for the reason of “making use

of private dynamism”. It is also said that the Ministry of Finance is

opposed to nationalization.

At present, the cost of reprocessing is included in electricity bills,

and each power company entrusts the funds with the public utility

foundation Radioactive Waste Management Funding and Reserve Center in

accordance with their nuclear power generating capacity. However, it is

said that even with this system to protect reprocessing, there is a

possibility that power industry deregulation will force the

reprocessing project into liquidation.

The author insists that maintaining the reprocessing project is

unnecessary, but many of the subcommittee members claim that

reprocessing is required for reasons of national policy. A proposal to

commission the reprocessing project to the private sector has also been

presented to the subcommittee. While a specific policy proposal is yet

to be put forward, in order to maintain reprocessing under the excuse

that “it will lead to benefits for the whole country”, a mechanism is

being sought for levying the cost of reprocessing widely across

consumers, including those who use renewable energy.

The spent nuclear fuel problem

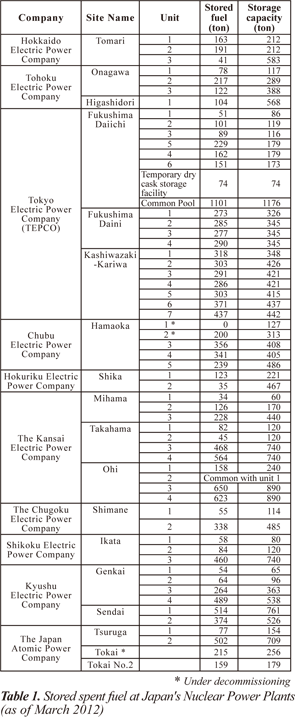

The problem of spent (waste) nuclear fuel came up for discussion at the

sixth meeting, but there was no serious discussion on the handling of

the roughly 17,000 tons of spent nuclear fuel that has continued to

accumulate in the spent fuel pools at each of the nuclear power plant

sites (

Table 1).

Without the approval of the prefectures that host nuclear power plants

to store spent fuel onsite, it is necessary to construct storage

facilities outside the prefecture, but it seems that this approval will

not be easily obtained. Since the power companies are the owners of the

spent fuel, they are required to secure the storage capability. The

power companies have avoided the storage problem saying that if

reprocessing proceeds as expected, then securing new storage sites will

become unnecessary. For this reason, as we have seen with the voicing

of opinions in the subcommittee, there appears to exist the optimistic

notion that if the government will support reprocessing then this will

resolve the spent fuel storage problem.

Fast reactor or fast breeder reactor?

Fast reactor or fast breeder reactor?

At the sixth meeting, mysterious documentation on Monju was handed out

by the secretariat. Handouts in the subcommittee consist of

“documentation” and “reference materials”. Both included precisely

identical nuclear fuel cycle diagrams, but in the “documentation” this

was labelled “Fast Reactor Cycle”, whereas the “reference materials”

carried the label “Fast Breeder Reactor Cycle”. Further, with reference

to the Rokkasho reprocessing plant, included in the same nuclear fuel

cycle diagram, the “documentation” labelled the plant as “In the final

testing stage”. While the “reference materials” labelled it as “In the

final testing stage: Improvement of the facility for high-level liquid

waste vitrification (scheduled for completion in October 2014)”.

The author believes that this can be taken as a formal change of policy

from the former fast breeder reactor development to fast reactor

development. Moreover, the “Monju Research Plan” announced in 2013 gave

the term “fast breeder reactor/fast reactor” showing equivalence for

both types of reactor.

The Basic Energy Plan (April 2014) positioned Monju as “an

international research base for volume reduction and reduction of the

degree of toxicity of waste materials and improvements in technology

related to nuclear non-proliferation.” Monju was constructed as a fast

breeder prototype reactor, but if it has lost its position as a breeder

reactor, it will be necessary to devise a new raison d’Ítre for it.

That is, volume and degree of toxicity reduction. As Japan is totally

at a loss about how to resolve the high-level waste disposal problem,

if it can be said to be “useful for volume reduction”, it might then be

easier to gain acceptance for a restart of operations at Monju.

Doubts about the potential for reduction in the degree of toxicity

Reduction of volume and the degree of toxicity is nothing new. In the

latter half of the 1980s, active research efforts were made into what

was known as partitioning and transmutation research and the

Phoenix Project. Research involving international cooperation was also

carried out under the Omega Plan (A Proposal to Exchange Scientific and

Technological Information Concerning

Options

Making

Extra

Gains of

Actinides

and Fission Products Generated in the Nuclear Fuel Cycle under

OECD/+NEA International Cooperation), but had to be abandoned due to

the inability to derive practical applications.

The subcommittee documentation claims that if spent nuclear fuel from

Light Water Reactors is reprocessed and vitrified, the volume will be

reduced to one quarter of the original, and further, will be reduced to

one-seventh of the volume by the use of a fast reactor. However, it is

meaningless to compare just the volumes of the spent fuel and the

vitrified product. Uranium separated out by reprocessing is itself a

waste product, and large amounts of radioactive waste materials are

also produced in the process of reprocessing. It is the total volume of

all this waste that should be compared. It is also calculated that the

degree of toxicity after 1000 years will be twelve thousandths

(12/1000) for LWR spent fuel directly disposed of after reprocessing,

but four thousandths (4/1000) if reprocessed by fast reactor.

Using a fast reactor to bombard the spent fuel with high-energy

neutrons will theoretically cause the minor actinides (Americium and

Neptunium etc.) to fission, but this author believes that it is

actually impossible, or extremely difficult, to realize this

assumption. Whether or not the minor actinides can be fully separated

from the high-level radioactive waste liquid separated out by

reprocessing, and whether the minor actinides can be made to fission

smoothly in the fast reactor are in doubt. In some cases, there is a

fear that radionuclides with an even longer half life will be produced.

Even if the technological outlook for this is favourable, the process

of removing the minor actinides from the high-level radioactive waste

liquid and then a process for fabricating the fuel using remote

equipment would be required, necessitating a large-scale and complex

facility for realization.

The significance of using Monju for volume reduction research, from

which successful outcomes cannot be anticipated, is something that

requires a serious rethink.

Contributions to global non-proliferation?

Contributions toward global peaceful use of nuclear power was the theme

of the seventh meeting. A presentation was given by Dr. Charles D.

Ferguson, President of the Federation of American Scientists. What

remained in my impression of his presentation was the sentence, “We now

stand at the juncture of whether the world will be contaminated by the

nuclear inferno or destroyed by climate change.” That the solution for

this is nuclear power is something that I cannot accept. This author’s

position is that whatever mechanisms are introduced into nuclear power

plants, they will never be able to reduce the risk of proliferation to

zero, and climate change can be mitigated by means other than nuclear

power plants.

There was no new content concerning proliferation in the subcommittee’s

documentation. The government wishes to claim that it can contribute to

the global peaceful use of nuclear power through the export of nuclear

power plants, and the grounds for this, it was explained, was that

thoroughly ensuring peaceful use through bilateral agreements can

prevent proliferation.

This author, however, is concerned that the export of nuclear power

plants will, conversely, lead to nuclear proliferation, and not

contribute to non-proliferation. I emphasized that preparing a position

document on actual cases of bilateral agreements that allow

reprocessing will probably not contribute to non-proliferation.

(Hideyuki Ban, Co-Director of CNIC)

1) Please see the article in NIT 161 at http://www.cnic.jp/english/newsletter/nit161/nit161articles/02_HLW.html

2) http://www.meti.go.jp/committee/sougouenergy/denkijigyou/genshiryoku/pdf/005_03_00.pdf

3) http://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/npu/policy09/pdf/20111221/hokoku_kosutohikaku.pdf (In Japanese)

Return to

Energy Policy / Nuclear Trends / Nuclear Industry page

Return to NIT 163 contents