Group Introduction Phase-Out Nuclear Energy Downtown Network: a grassroots gathering place Nuke Info Tokyo No. 114

By Shun’ichi Uchiyama*

|

|

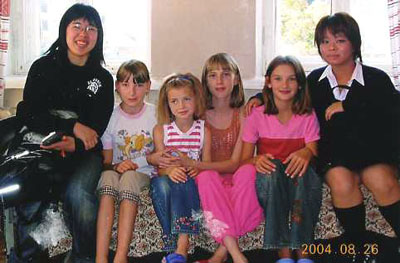

Downtown Tokyo high school students Mayuko Suzuki (L) and Mina Hosoi with children in a children’s hospital in Kiev

|

Chernobyl was a terrible accident. Despite what the government and the power companies say, in a small country like Japan, there is no safe place left. With this in mind, in 1989 a national citizens’ movement, led by Jinzaburo Takagi, launched a petition for the enactment of a nuclear phase-out law. In East Tokyo the Phase-Out Nuclear Energy Downtown Network joined this movement, demanding that the right to choose a safe environment be returned to the citizens.But no matter how fervent the plea, for it to become a reality certain practical conditions must be met. In this, the role of the Downtown Anti-War Movement was indispensable. At the time of the nuclear phase-out law petition, this movement had sections in all the administrative districts in East Tokyo. Since its founding in 1982 it had been holding “Downtown Anti-War Gatherings”. The focus of these gatherings was “No more Tokyo firebombings!” Coops, unions and citizens’ groups were the prime-movers in the movement and they got together to form the Phase-Out Nuclear Energy Downtown Network. The network was initiated by six people, including representatives from these groups and a lawyer. It started up with 120 group and individual members.

The original name of the network was Phase-Out Nuclear Energy Law Downtown Network. We demanded a reversal of Japan’s nuclear-based energy policy and collected signatures for the nuclear phase-out law petition. Then in the autumn of 1990, we were contacted by mothers of Chernobyl victims in Kiev. They asked if we would invite them for a brief visit to Japan. Downtown Tokyo is a place with a strong sense of duty and humanity. But besides that, this request from Kiev provided us with an opportunity to broaden the age range of people involved in our work and to engage in cultural exchange, so we decided to add a new dimension to our movement.

Their visit provided an opportunity to spread the message about the danger of exposure to radiation from nuclear power plants and to become involved in relief and exchange activities for victims. Focusing on Kiev, to date we have sent thirteen shipments of medicine, invited children to visit on two occasions and sent four delegations from Tokyo. Each time we made do with donations to cover costs and the labor was left in the hands of whoever was available. Our wish is that through our activities we might make some small contribution to the cause. Our style of operating is reflected in our motto: “Stick with it, use what is available, and take responsibility for your own ideas”.

In June this year we invited Natalia Baranovska, a researcher at the Chernobyl Museum, to Tokyo. This was part of our ongoing exchange program. The idea came when a group of downtown high school and university students visited the Chernobyl Museum in 2004. They mentioned the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and asked Natalia to come to downtown Tokyo and visit a high school here. We wanted to show her how we live. The program included visits to a high school class, to the work places of network members, to a government office, to nuclear-related places, and to various cultural sites, including the famous Asakusa Shrine in downtown Tokyo.

While Natalia was in Tokyo, she paid a visit to an evening class at the Arakawa Commercial High School. The students had all come straight from their daytime jobs. After the lesson one of the students said, “Natalia’s talk was about a time when we were just born.” It was a poignant reminder to us that if we had managed to prevent the accident, the evening’s talk wouldn’t have been necessary.

1. The phrase translated here as “grassroots gathering place” literally refers to gossipers gathering around the village well.