Fukushima:Radiation Dispersed over a Wide Area Nuke Info Tokyo No. 142

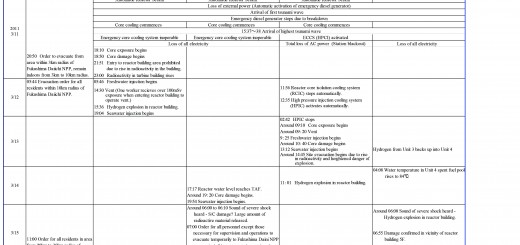

Radiation released by the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station has scattered over a wide area. It is thought that this dispersion of radioactive material has been caused mainly by hydrogen explosions in three of the reactors. The reactor vessels and containment vessels have been damaged and radioactive pollution, not only of the atmosphere but also of the sea, has begun. It is clear from measurements of published air dose rates at different locations that the dispersal depends largely on wind direction and topology.

Estimating the amount of radioactivity emitted from the radioactivity monitoring data, the Nuclear Safety Commission (NSC) raised the accident level to 7 on April 12. According to the NSC announcement, the amount of radioactivity calculated as the equivalent of emitted iodine was estimated at 370,000 to 640,000 terabecquerels (1 tera = 1012). However, this refers only to atmospheric dispersal and does not take into consideration the problem of the amount of radioactivity in the polluted water that has accumulated in the turbine building and elsewhere.

Each prefecture has also published air dose rates (see Figure 1). Looking at the figures for Fukushima Prefecture, the peak was 44.7 Sv/hr (microSieverts/hour) in the area of Iitate Village outside the 20 km evacuation zone. Even at Fukushima City, 60 km from the accident site, the dose rate exceeded 20 Sv/hr. In Tokyo, 0.2Sv/hr were detected; too small a value to show in the figure, but several times larger than normal. Since the value would normally be less than 0.1 Sv/hr, this shows that extremely high values were observed in areas downwind from the accident site.

Each prefecture has also published air dose rates (see Figure 1). Looking at the figures for Fukushima Prefecture, the peak was 44.7 Sv/hr (microSieverts/hour) in the area of Iitate Village outside the 20 km evacuation zone. Even at Fukushima City, 60 km from the accident site, the dose rate exceeded 20 Sv/hr. In Tokyo, 0.2Sv/hr were detected; too small a value to show in the figure, but several times larger than normal. Since the value would normally be less than 0.1 Sv/hr, this shows that extremely high values were observed in areas downwind from the accident site.

From the point of view of personal exposure, external exposure can be estimated from exposure duration. Since these are outdoor air dose rates, in times of high doses the indoor dose rate would fall to less than half of the value. It is also necessary, however, to take into account exposure from inhalation of radioactive material.

Radioactivity released into the environment not only affects the atmosphere (see bottom of the left-hand column on p.7), but also results in pollution of the soil and various kinds of food and drink. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) has released the results of a strengthened observation system. One example of this is shown in Table 1, below. Provisional regulation criteria have been set for radioactive iodine and cesium, samples taken and studied, and distribution of produce found to exceed the criteria has been prohibited.

The criteria are monitored for the radioisotopes iodine-131, cesium-137, and sometimes cesium-134. These isotopes disintegrate through beta decay and simultaneously or subsequently emit gamma radiation of a particular energy, making them easy to detect and measure. That is why they have become radiation indices. The safety levels and the published measurement results do not mean that there is no pollution by other types of radioactive material, but that radioactivity from elements other than iodine and cesium is not measured. However, looking at the development of the accident, it is unlikely that radioactive strontium has been widely dispersed.

As well as iodine-131, iodine-132 has also been released, their half-lives being eight days and 2.3 hours, respectively. After three months, the amount of iodine-131 will fall to one-2000th of what it was originally. Thus, the problem of iodine pollution resolves itself relatively quickly and is not thought to have an impact on subsequent plantings.

Contrastingly, radioactive cesium is much more troublesome. The cesium isotopes that are the problem are cesium-134, with a half-life of two years, and cesium-137, with a half-life of 30 years. Cesium pollution is thus long-term. From case studies of the Chernobyl nuclear accident, it is known that the greater part of the cesium remains in the surface layer of the soil (roughly the top 20 cm), and is leached out only very slowly by rain. However, how much of the cesium in the soil migrates to crops appears to depend on the soil and the type of crop, and is not well understood.

Assistant professor Tetsuji Imanaka of the Kyoto University Research Reactor Institute very quickly visited Iitate Village at the beginning of the crisis and has reported on the state of radiation pollution of the environment there. (www.rri.kyoto-u.ac.jp/NSRG/seminar/No110/iitatereport11-4-4.pdf [in Japanese]) The pollution was extremely high and it is thought that the highly polluted areas will not be habitable for some considerable period of time.

For the sake of our health, the government should lower the provisional regulation criteria and reduce the possibility of internal exposure as far as possible. On the other hand, since this would be a serious blow to producers, they should be provided with adequate compensation. Further, since produce below the criteria is distributed, we have no way of knowing to what degree each food item is polluted with radioactive material. I think the only thing that we can do as individuals is look at the data published by MHLW and by each prefecture and make informed choices about what might or might not be safe.

Hideyuki Ban (CNIC Co-Director)