JCO Criticality Accident: five years on Nuke Info Tokyo No. 102

Five years have passed since the JCO criticality accident at Tokai Village. Two people died, compared to the five people who died in the Mihama-3 accident. At the time of the JCO accident Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) said it had nothing to do with them. Then came the TEPCO scandal (NIT 92 Nov./Dec. 2002). On that occasion it was Kansai EPCO which said it had nothing to do with them. But what everyone now knows is that the nuclear safety system leaks like a rusty bucket. We keep hearing that everything is OK because the government has rules in place and the power companies obey the rules, but it was all false, not just for JCO, but for TEPCO and KEPCO too.

Investigations into the Mihama-3 accident have only just begun. We won’t know the details of the sequence of events that led to that accident for some time. However, in the case of the JCO accident, the investigations and the court case have finished (NIT 94, 97) and it is now possible to read the record of the investigations that were carried out and the evidence that was presented. The people quoted are mostly JCO workers and former workers, but workers from Japan Nuclear Cycle Development Institute1 (JNC) are also quoted. Besides these records, there are also various documents from JCO, from the Science and Technology Agency, from JNC’s predecessor the Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corporation (PNC), and so on. The majority of these documents were not published during the Nuclear Safety Commission’s investigations and this article picks up things that we have found out from reading them.

First I will deal with the safety screening process. The Conversion Test Plant, where the accident occurred, was built in 1979. Originally it was only used to produce uranium powder. In 1983 JCO applied for permission to raise the enrichment level and to produce a solution, whereas previously it had only been producing a powder. (It was while producing this solution that the criticality accident occurred.) It wanted to make this solution for PNC, but it turns out that the Science and Technology Agency (STA) officer in charge of the screening process was not really an STA man at all. He was a PNC man who had been seconded to STA for two years. In 1984, immediately after he approved JCO’s request, he returned to PNC. One gets the feeling that he went to STA for the specific purpose of handling this case.

Only the raised enrichment level of the powder was considered during the screening process. The issue of producing a highly enriched uranium solution was not examined. It was stated in the application that a solution would be produced, but the production method was not mentioned. The Conversion Test Plant was designed to produce the powder form. It had no equipment for producing a solution. Therefore it was necessary to use equipment designed to produce a powder, even though the high uranium concentration of the solution meant that it was likely to go critical2. But this is what the government (STA) approved. The workers wouldn’t have used equipment meant for a powder if proper equipment had been available. They wouldn’t then have been forced to resort to irregular procedures.

This uranium solution (uranyl nitrate) was used to make fuel for PNC’s Joyo. It was mixed with a plutonium solution from the Tokai Reprocessing Plant, then removed from the nitrate solution and made into MOX (mixed oxide) fuel. Joyo was an ‘experimental’ reactor that was used to perform experiments for the Monju prototype reactor. If experiments burning fuel in Joyo were delayed, the schedule for Monju would also be delayed3. So the abovementioned safety screening process was rushed and a thorough investigation was never done. From the point of view of safety, approval would never have been given. The key issue then was this Monju-Joyo-JCO hierarchy.

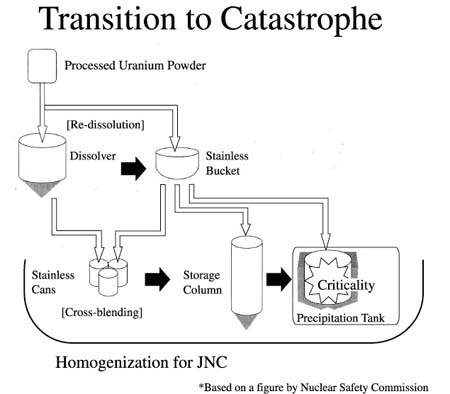

The safety inspection was carried out in the early ’80s, but in the early ’90s JCO was again influenced by Monju. The MOX fuel for Joyo and Monju was produced at the same factory, so fuel couldn’t be made for Joyo at the same time as fuel was being made for Monju. PNC first made fuel for Monju in 1989. However problems arose which doubled the time taken to produce the fuel. As a consequence the schedule for producing fuel for Joyo was delayed and this delay flowed on to JCO’s schedule for producing the uranyl nitrate solution. It was in 1993 that JCO started using its infamous stainless steel buckets for redissolution. Then in 1995 it started to use the storage column for the homogenization process, even though the storage column was not intended to be used for that purpose. (See diagram.)

However at the time of the accident they were trying to homogenize the solution in the Precipitation Tank, instead of the Storage Column. Why? The reason wasn’t understood until recently, but it now seems that it was related to STA’s tours of inspection. In order to carry out homogenization in the Storage Column, given that it was not designed for that purpose, it was necessary to fit an improvised pipe. But this was illegal, so they couldn’t let STA see it. By using the Precipitation Tank instead, since homogenization could be carried out without fitting a special pipe, it was possible to avoid fitting and removing the temporary pipe every time an STA inspector visited. (Of course the Precipitation Tank wasn’t meant to be used for this purpose either.) This, according to the worker who survived the accident, was one of the reasons why the Precipitation Tank was used. But whereas the Storage Column was protected from going critical by geometrical control4, the Precipitation Tank was not so protected. Thus the catastrophe occurred.

These things have come to light as a result of the court case. Finally I will touch on a problem that has arisen since the court case, namely the preservation of the equipment in the Conversion Testing Plant (see NIT 97). The site of the accident is now under threat. As long as the court case continued this equipment was protected, but it has now been returned to JCO, which plans to dismantle the Precipitation Tank and so on, load it into drum cans and dispose of it as radioactive waste. Once this happens, we will no longer be able to carry out investigations into the causes of the accident at the site itself. The Mayor says it should be preserved, but the village council supports the plan to dismantle it. They say that in place of the real site a replica will be constructed. However we believe that the site should be preserved. It is necessary to preserve the site so that people don’t forget the lessons of the criticality accident. Otherwise the nuclear safety system will remain, as described at the beginning of this article, a rusty bucket.

Satoshi Fujino (CNIC)

(1) JNC (previously PNC) is the government funded research and development organization that owns the Joyo experimental fast reactor. The accident occurred while JCO was producing a uranyl nitrate solution to be used to make fuel for Joyo.

(2) It was necessary to process the uranium in small batches in order to prevent it from reaching critical mass. But JCO didn’t want to do this. It only said that it would do so in the written documentation.

(3) Monju was then, and is now still, officially ‘under construction’. Trials were conducted for almost two years until the 1995 Monju accident, since which time it has not operated.

(4) Geometrical control means that the dimensions of the container are designed so that it is physically impossible for the contents to go critical (assuming the enrichment level does not exceed the design limit).