Former nuclear plant worker Ryusuke Umeda’s legal action for workers’ compensation Important testimony discloses the harsh reality of the work environment in NPPs -Nuke Info Tokyo No. 168

In 1979, Ryusuke Umeda was engaged in periodic inspections of the Shimane-1 and Tsuruga-1 nuclear power plants and suffered a myocardial infarction in March 2000. He filed an application for workers’ compensation with the Shimane Labour Standards Supervision Office in Shimane Prefecture in September 2009, and in February 2010, he presented his case to the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW), complaining about the actual conditions of the work environment at the nuclear plants.1), 2)

However, his application was rejected and the two requests he made for an examination by a review committee were also turned down. In February 2012, he therefore filed a suit against the state with the Fukuoka District Court, demanding reversal of the decisions.

On May 15, former nuclear plant worker Seiji Saito and former radiation controller Hiroshi Masumoto testified before the grand bench of the district court. Mr. Masumoto had worked for Okano Valve Co. as radiation controller since 1963, and was dispatched to a number of nuclear power plants equipped with boiling water type reactors. He was charged with maintenance and management of the reactors. This was the first-ever testimony made by such an official, and is therefore highly significant. We hope that many people will pay great attention to this trial, in which we will hear important and notable testimony. The team of lawyers for the plaintiff is comprised of many passionate young men and women, and heated debates are expected in the trial. (by Mikiko Watanabe)

Report on the Umeda case trial

By Lead Lawyer Toshimasa Kabashima

In response to Mr. Umeda’s application for workers’ compensation, the state pointed out the following debatable points.

- There is not sufficient scientific data to prove the relation between his exposure to radiation of less than 1-2 Gray and his myocardial infarction.

- According to a recent epidemiological survey on survivors of the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it is not clear if those exposed to radiation of less than 0.5 Sv had a significantly higher risk of developing a cardiac disorder.

- The 2007 recommendation by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) stated that none of the currently available data show that exposure to radiation of less than 100 mSv will have an impact on non-cancer diseases.

- Cardiac disorders form a category of diseases associated with adult lifestyle habits, such as smoking, obesity, and high blood pressure, and have nothing to do with exposure to radiation. The fatality rate is 144.4 per 100,000 people.

- The plaintiff had several risk factors that might have caused myocardial infarction, including diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking. Given this fact, the refusal of his application for workers’ compensation was legitimate and appropriate from the medical viewpoint.

Citing these reasons, that are virtually impossible for a layman such as Mr. Umeda to deal with, the state rejected his ardent attempt to obtain workers’ compensation.

Moreover, the state claimed that Mr. Umeda’s exposure dose of 8.6 mSv was extremely small, slightly more than the 6.9 mSv dose a person receives when undergoing a computed tomography scan of his chest.

These reasons seem to indicate that the state has a strong interest in rejecting nuclear plant workers’ applications for official compensation by any means possible.

Most nuclear power plant workers are believed to be paid relatively high wages while they are working. Nevertheless, once they fall into bad health and become ill due to excessive exposure to radiation, they must stop working. To pay for medical treatment and for living, they are forced to dip into their savings, which is the last resort for them, and tend to run out of money. Consequently, many such workers suffer from both extreme poverty and ill-health.

The employers gain profits from the labor provided by their workers, while the workers are likely to suffer great distress and pain should they sustain injuries or fall ill. The workers’ compensation system was originally established to rectify this injustice.

Thus the prevailing practice is that the state designates such a worker’s case as a no-fault liability case if the relations between his work and his sickness are evident, and speedily takes the simplest procedures to relieve the ailing worker. This principle should be applied to the case of a nuclear plant worker engaged in regular inspections. If a nuclear plant worker submits evidence to prove that he was exposed to radiation while engaged in the work, and to prove that his sickness has an undeniable causal relation with his exposure to radiation, the state should provide workers’ compensation to the worker unless it obtains firm evidence that the sickness was caused by other factors.

Mr. Umeda’s case is Japan’s first workers’ compensation suit filed by a nuclear plant worker suffering from a myocardial infarction. Since Japanese nuclear power plants became operational, the number of workers engaged in the operation and regular inspections of the reactors may total several hundreds of thousands, but only 48 cases have been filed so far by such workers for the purpose of obtaining workers’ compensation on account of exposure to radiation. Of these, 10 cases were officially recognized as work-related ailments, all the plaintiffs in these cases suffered from cancer.

Meanwhile, in suits filed by atomic-bomb sufferers, myocardial infarction was recognized as one of the atomic bomb-related illnesses, and in the class actions launched in and after 2003, some myocardial infarction patients successfully won workers’ compensation.

Mr. Umeda was engaged in periodic inspection at nuclear power plants for 43 days in total. He worked for 13 days, from February 6 through February 9, and from March 2 to March 10, at the Shimane nuclear power plant, and later, for 30 days, from May 17 through June 16, at the Tsuruga nuclear power plant. His exposed work hours were 35 minutes per day at the shortest and about three hours at the longest. The company which undertook the periodic inspection work was not able to force him to work longer because the ambient radiation dose level at the work site was too high. Inevitably, human wave tactics (large-scale mobilization of labor) were used.

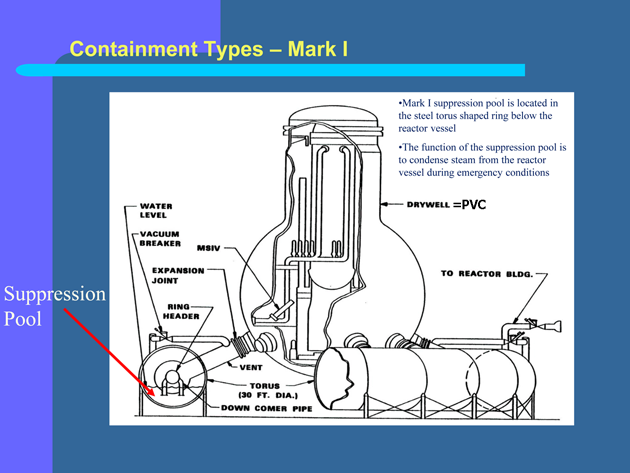

Mr. Umeda worked mostly in the primary containment vessel (PCV), doing the work of, for example, cutting and removing corroded pipes, welding and fitting new ones, replacing instrument piping, removing shield plugs, installing lead-wool sheets, pasting plastic sheets on the floor, installing scaffolding, scooping up contaminated water accumulated on the floor in the PCV, and wiping up the water with waste cloth. In addition, he was obliged to do the work of using waste cloth to clean the walls and floor of the reactor pressure vessel (RPV), where the radiation dose level was extremely high, and the work of replacing the instrument piping for meters and gauges connected to the RPV. Besides these, he was engaged in other work, such as cutting and replacing piping in the turbine building and the reactor building, where the radiation dose level was also considerably high.

Structure of BWR containment

Structure of BWR containment

From GE website: files.gereports.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/containment-lg.jpg%5B/caption%5D

The bottom-level subcontractor workers were not taught about the harmful effects and dangers of radiation on human bodies while they were conducting these operations. This is why Mr. Umeda worked at the Shimane nuclear power plant in ordinary work clothes, without wearing a mask or carrying an alarm meter. At the Tsuruga nuclear power plant, he worked wearing a radiation protection suit, but took off the mask when it was hard to breathe because of high temperature and high humidity at the site, or when the mask became fogged and made it difficult for him to see.

Furthermore, he continued to work while leaving his portable dosimeter and alarm meter with other people, because he had a strong sense of responsibility and thought that it would disturb the work if the alarm should go off.

Emergence of symptoms of acute radiation injury

After completing his task at the Tsuruga nuclear power plant, Mr. Umeda returned home to Fukuoka City in Kyushu on June 16, 1979. He soon experienced symptoms of nose bleeding, nausea and vertigo from unknown causes. He also felt fatigue, which prompted him to go to several medical institutions. The clinical record that remained in the Kyushu University Hospital shows that Mr. Umeda had visited Kokura Medical Association Clinic, Kenwakai General Hospital, and Mihagino Hospital, all in Kita-kyushu City. The data also said he had visited the Nagasaki University Hospital in Nagasaki City, the Kyushu University Hospital in Fukuoka City, and several other medical institutions, for treatment of fatigue, a sense of exhaustion, palpitations, vertigo, and nose bleeding from unknown causes. These symptoms were commonly seen among atomic-bomb sufferers immediately after the bombing. This means that Mr. Umeda must have been suffering acute radiation sickness at that time.

The Kyushu University Hospital’s medical records also revealed that Mr. Umeda received a whole-body counter test at the Nagasaki University Hospital on July 12, 1979, the result showing that radionuclides of cobalt, manganese, and cesium were detected in his body. This proves that he had internal exposure to radiation.

State ignores opinions of medical doctors

When Mr. Umeda filed his application for workers’ compensation in September 2008, a radiologist at the Nagasaki University Hospital wrote in his medical report that the gamma-ray spectrum believed to have been emitted from the aforementioned cobalt, manganese, and cesium-137 in Mr. Umeda’s body was detected, and that it is highly likely that there were radioactive substances in his body that are not detected under normal conditions (internal exposure). He went on to say that Mr. Umeda had such symptoms as nausea, fatigue, and hemorrhaging at that time, and that a hospital medical examination revealed that he was also suffering from leucopenia. Considering all of these facts, he concluded that it was undeniable that Umeda had received a large exposure to radiation of a level close to acute radiation injury, and that it is also undeniable that his exposure to radiation around 1979 had something to do with the occurrence of the myocardial infarction.

This medical report seems to have been made by taking into account the ruling handed down by the Nagasaki District Court in May 1993 in the suit filed by Nagasaki atomic-bomb sufferer Eiko Matsutani. The ruling stated that if there is a possibility for the plaintiff to have been exposed to radiation, the person should be officially recognized as a patient with A-bomb sickness. With this ruling, Matsutani won the case. The defense council appealed the case to a higher court, but this was rejected in November 1997, and the ruling was finalized in March 2000 after the Supreme Court dismissed the appeal against the ruling.

Coupled with the radiologist’s medical report, there was also an earlier “new guideline on the screening of A-bomb sickness patients” formulated by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, which states that a myocardial infarction patient with a radiation exposure dose of more than 1 mSv should be readily recognized as suffering from A-bomb sickness. In view of these two factors, the state should have recognized Mr. Umeda as a sufferer of sickness caused by exposure to radiation and granted him workers’ compensation.

Nevertheless, the state continues to firmly reject his application, citing reasons that are incomprehensible even for medical experts, and ignoring the radiologist’s medical report.

State’s response to the trial

Apart from focusing on medical issues, the state conducted examinations of five witnesses who had worked at the nuclear power plant around the same time as Mr. Umeda had.

The following is an outline of their testimonies.

- Within the Shimane nuclear plant, the radiation dose was not high and also the radioactive contamination level was relatively low. The witness had therefore never put on the full-face mask, nor heard the alarm against high radiation dosage setting off within the PCV. He also testified that he had never worn the red-color work suit (the protective gear for high-level radiation areas) there. (This is consistent with Mr. Umeda’s recollection.)

- Within the PCV, the radiation dose was high and there was no place where workers could hide dosimeter or other items.

- There were work plans, but no work quota.

- The employers provided radiation-related training repeatedly until the workers gained full understanding of its contents.

- No workers were forced to leave dosimeters with the employer, and no one actually did so.

This testimony was presented apparently with the intention of proving that the 8.6 mSv exposure registered in the record was correct.

Trial of the nuclear plant worker vs. the state

The lawyers for the plaintiff conducted examinations of two witnesses, in addition to the plaintiff Mr. Umeda. One of them was Seiji Saito, who was engaged in the regular reactor operation for a long time as a subcontractor worker, and the other, Hiroshi Masumoto, who was a second-tier subcontractor employee in charge of radiation control. The second-tier subcontractor dispatched the plaintiff and other workers hired by the bottom-level subcontractors to the regular inspection sites.

Mr. Saito suffered a thyroid gland tumor (hematoma), acute myocardial infarction, and bilateral cataracts, while Mr. Masumoto had high blood pressure, stomach cancer, lung cancer, a cataract, narrowing of the aortic (aortal) valve, among other illnesses. Both of them were seriously ill, suffering from a number of sicknesses that were apparently caused by radiation exposure, and they had to testify at the risk of their own lives.

Mr. Saito testified that the workers hired by low-level subcontractors had been severely discriminated against in the radiation-related work sites, so he organized a labor union and fought against discrimination by presenting 20 demands. However, he was attacked by union-busters, he said.

Mr. Masumoto testified that the first-tier subcontractor had measured the air dose of the work site in the morning before the work began, handed the data to the second-tier subcontractor, and the company’s radiation dose controller had allocated tasks to each worker.

In the work site, however, workers walked around, used various tools, cut pipes and did other types of work which push up the area’s radiation dose to a higher level. Mr. Masumoto said he had allocated work by taking this into account, but many other radiation controllers had not done so. He alleged that he had given only 30 minutes work to each worker when the dose level within the PCV became too high. In such a case, he said he had to use many workers for a minor task of, for example, removing a bolt that was stuck fast in packing on a large valve. He described the real situation of the work site vividly and in detail.

We call on readers to extend greater support to NPP workers seeking workers’ compensation

The trial will soon enter the stages of 1) epidemiological analysis of radiation exposure and illness and scientific estimates of exposure dose, and 2) experts’ submission of their opinions concerning internal exposure, etc. and their testimonies.

The plaintiff’s lawyers obtained support from several dedicated experts, while the state plans to ask experts from the “nuclear village,” a tightly-woven network of regulators, utility industry executives, engineers, and academics, to testify. The plaintiff’s lawyers are poised to make the trial very realistic and based on facts concerning nuclear plant working conditions and workers’ exposure to radiation, and will try to avoid long-winded arguments based on desk theory. We feel that there are bright prospects for victory in this trial.

The plaintiff Mr. Umeda, his lawyers and his supporters’ group are determined to step up their efforts to save nuclear plant workers who have been ignored by society for a long time, and to help them restore their human dignity. We hope readers will extend their warm and sincere support to them.

1) Ryusuke Umeda Lodges Historic Workers’ Compensation Claim (NIT 135 March/April 2010)

cnic.jp/english/newsletter/nit135/nit135articles/umeda.html

2) Ryusuke Umeda’s Worker’s Compensation Claim Rejected (NIT 139, Nov./Dec. 2010)

cnic.jp/english/newsletter/nit139/nit139articles/umeda.html