The history of the anti-nuclear movement on the Kii Peninsula

Women and fishermen keep Wakayama nuclear free

by Matsuura Masayo, No Nukes Wakayama

In the latter half of the 1960s, Japan was in a period of high economic growth. That was the time when nuclear power plant issues began to emerge in Wakayama. From 1967 the municipal councils of three districts decided to try to attract nuclear power plants (NPPs) to their district. But this decision was made with no public consultation and people became suspicious when land was bought up. Protests were raised, mainly by fishermen and mothers.

Local communities did not at first know anything about NPPs and even thought that they could wash away the sludge that had built up in fish and pearl cultivation areas with the hot waste water from the nuclear plant. Taiji, one of the districts neighboring the two pro-nuclear districts, made a resolution to oppose nuclear construction and people from a women’s group in Taiji went to the neighboring districts to hand out leaflets explaining the dangers of NPPs. Residents in all the districts attended lectures by engineers who had studied nuclear energy in the US as well as ordering science journals from the US and tried to learn as much as possible about nuclear power. They then realized that hot waste water from NPPs has a severe impact on fish and the two kilometer area surrounding NPPs is extremely dangerous. They became strongly opposed. At the center of the opposition was mothers, who wanted to make sure their children could enjoy unspoilt blue sky, beautiful sea and mountains. They formed a group and distributed leaflets and raised funds for their activities. Over a period of four years, the local council resolutions changed from being pro-nuclear to anti-nuclear. Even after that, still the pro-nuclear camp did not give up but in the southern part of the Kii Peninsula, plans to build nuclear power plants were defeated.

In the mid 1970s, Wakayama again became a candidate site for NPPs. Two sites were proposed, in Hidaka district and Hikigawa district.

In 1975, the plan emerged for the second time. This time, in a masterly display of pro-nuke groups joining forces, Kansai Electric Power Company (KEPCO), the Hidaka municipality and the district council set up a special committee on the NPP in just a week and completed the land assessment, leaving only the marine impact assessment unfinished.

Then in 1976, there emerged a plan to attract an underground nuclear power plant in Hikigawa district. Hikigawa council decided to sell land it owned to KEPCO. The land was sold to a council-run development company by residents who were told it was to become a nature reserve. An elderly person who helped with the land sales committed suicide when he found out that he had been fooled into facilitating the process to build a nuclear power plant. In April of that year a request to assess the land for the construction of the plant was received, but in July there was an election and the residents managed to get an anti-nuclear mayor elected.

In 1978 in Hidaka district, even though the tension regarding the NPP was rising, the fishermen remained non-committal, not engaging in protest activities. Their wives, however, formed a women’s group against the NPP and collected 300 supporting signatures from residents of the coastal area. Despite the women’s protest, the fishing union was about to approve the nuclear plant on the condition that a marine impact survey be conducted first, when the Three Mile Island (TMI) nuclear accident occurred in March 1979. Under these circumstances, Hidaka Council had no choice, they had to put the nuclear plan on temporary hold.

After the TMI nuclear accident, anti-nuclear movements spread from just local affected areas to larger areas and in 1981, a Wakayama Prefecture-wide group was formed. This enabled all of the local groups to engage in negotiations with the prefectural government together. Regular symposiums and networking meetings were also held and a newsletter was published to help connect people.

However, the pro-nuclear camp was not giving up. In 1980, at their request the national government issued a safety declaration and Hidaka Council, using this as an endorsement, restarted activities to build a NPP. Also, the Wakayama prefectural government changed its policy. It used to be very supportive of the ‘Three principles on nuclear power plants’ which are ‘to ensure safety, location suitability and agreement of residents.’ But in 1983 it became more interested in promoting nuclear power.

At this time, government interventions on the pretext of an illegal loan to the Fishing Union in Hidaka became extreme and the comments made by the Wakayama Governor also became more blatant. The Fishing Union incident started when it was revealed that it was in debt of close to 1 billion yen due to dubious financial dealings. It became clear in a court case that those in the Union who were in favor of the nuclear plant planned to use the compensation money they would receive from the plant operator to pay off their debt. It was also revealed that KEPCO had deposited 300 million yen in the Fishing Union’s bank account.

The Wakayama and Hidaka municipal governments pressured the Union to pay off their debt with KEPCO’s cooperation. But the fishermen opposed to the plant insisted they would pay if off themselves. The Fisheries Department in the Wakayama Government even sent an official instruction to the Fishing Union telling them not to submit a plan for paying off the debt themselves.

KEPCO set up offices near the candidate sites and every day three to five employees would make individual visits in the town to convince people that the NPP would be a good idea. The number of employees would increase to 20 or so at election time. They also offered residents all-expenses-paid trips to observe NPPs in other prefectures.

In the name of ‘stable electricity supply’ in the energy crisis, the national, and prefectural governments, together with KEPCO tried to destroy community democracy and tried to turn local autonomy to their own will. It might be an easy thing for the municipality and KEPCO to control the movements of the residents and smother their resistance.

But the anti-nuclear fishermen managed to weather these storms and protect the sea. If the marine impact survey result allowed the Oura NPP in Hidaka district, then construction would go ahead. This is the tense situation we were in.

At the beginning of 1986 the Wakayama Governor announced the results of the prefectural nuclear power research project team. A pamphlet was put together to advertise nuclear power as useful to promote the local economy and industries. Three million yen was earmarked in the prefectural budget to be used for nuclear related purposes.

In answer to the prefecture’s ‘rose colored pamphlet,’ the Wakayama Citizen’s Group Against Pollution printed 3,000 pamphlets titled ‘When the roses die: the dreams and realities of nuclear power.’

At that point, the Chernobyl nuclear accident happened. In April 1986, images of the blown out roof of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor and President Gorbachev’s response, that ‘we have experienced the aftermath of a nuclear war’ were deeply shocking. It seemed that Wakayama’s rose-colored pamphlet was completed but it was never distributed.

The local Chambers of Commerce in Hidaka and Hikigawa, however, were quick to endorse the construction of an NPP.

In January 1987, the Governor announced that ‘Japanese nuclear reactors are safe’ and that he supported the construction of a nuclear plant in Wakayama in order to stimulate the economy. The pretext of ‘energy crisis’ and ‘stable electricity supply’ had disappeared and in 1988 he even said he ‘wanted to build one or two reactors’ because of the state subsidies that the prefecture would receive. Even though the rest of the world was reconsidering their nuclear programs, Wakayama was moving full speed ahead towards nuclear. After the Chernobyl accident, there was not much in the way of new movements emerging. With the privatizing of the Japan Railways in 1987 and the splitting of the labor movement, sympathy and support of the anti-nuclear movement also decreased.

In 1988, two years after Chernobyl, the Hidaka Hiisaki Fishing Union was forced to hold its annual general meeting (AGM). For several years previously the meeting had not been held because of disagreements. At the AGM, it was announced that an amount of 670 million yen would be received by the union as compensation for the marine impact survey. But the fishermen, unfazed by the money, courageously refused to agree to the survey.

It was the boundless strength of the fishermen, who had been fighting against the nuclear plant for more than 20 years, which made their campaign before the AGM possible. They announced that they ‘wouldn’t eat or sleep.’ So as to stop the Ao district municipal administration from abandoning its anti-nuclear stance, in just three days, women managed to get the majority of the residents to sign a petition. Before the AGM, between 30 and 40 people went round all the areas to gather signatures. If it came to a vote at the AGM, it would only leave bad feelings between the fishermen and they wanted to avoid this at all costs, which is why they took action as if their lives depended on it.

As the Hikigawa municipality moved closer to bankruptcy, the mayor went from being totally against the NPP in 1976 to taking a cautious approach in 1980 to being fully pro-nuclear in 1983. In 1987 a pro-nuclear mayor was elected. The council passed a long-term general plan with construction of a NPP as its central pillar.

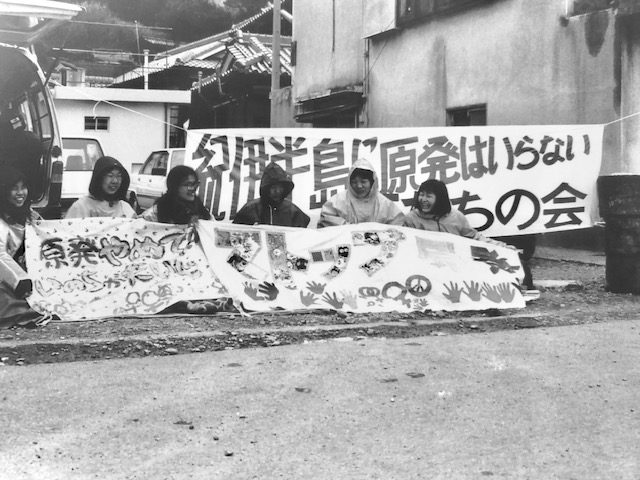

The women of Wakayama were feeling increasingly anxious about these moves and on April 26, the Chernobyl anniversary, they formed a coalition of five local groups. This motivated the formation of anti-nuclear groups in more districts and a movement of people across the Kii Peninsula who wanted to stop nuclear construction at all costs.

After the fishing union refused to cooperate with the marine impact survey, an anti-nuclear mayor was elected in Hikigawa district and a more than 20-year struggle was brought to a successful conclusion.

After that, the land which had been bought to build the NPP on, was donated to the Hidaka municipality for the reason that it was too hard for a corporation to maintain. The land for another candidate site was bought by the same municipality.

The land for another candidate site is still owned by KEPCO. Furthermore, KEPCO and related corporations are buying more land in the district. They also have an office and a location division.

Even though NPPs cannot be built, residents are concerned that the land will be turned into a radioactive waste dump. In 2018, in Shirahama district, two new citizen’s groups opposing nuclear waste were formed and activities continue.