Long-term Evacuation 10 Years After the Fukushima Nuclear Accident: Results of a Nationwide Survey of Nuclear Accident Evacuees

By Saito Yoko, Associate Professor and Senior Researcher, Institute of Disaster Area Revitalization, Regrowth and Governance, Kwansei Gakuin University

Introduction

The number of evacuees from Fukushima Prefecture due to the accident at the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station (F1) is currently said to be nearly 30,000. However, this does not include evacuees from neighboring prefectures, whose number is unknown.

Kwansei Gakuin University Institute of Disaster Area Revitalization, Regrowth and Governance was established on January 17, 2005, 10 years after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. Based on the philosophy of “human recovery,” the institute conducts research focusing on the humanities and social sciences. The term “human recovery” was used by Fukuda Tokuzo as a contrast to Goto Shinpei, who advocated the reconstruction of the imperial capital after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, to emphasize that the recovery should be a “human recovery” focusing on the “reconstruction of disaster victims” and “individual reconstruction.” Has “human recovery” been achieved in the 10 years following the Great East Japan Earthquake?

The Study Group on Evacuation, led by the Institute of Disaster Area Revitalization, Regrowth and Governance, conducted a “Nationwide Survey of Evacuees from the Nuclear Accident” in summer 2020 to grasp the situation of long-term evacuees over the past 10 years. This paper is based on an interim report released in November, but as the analysis of the results is still underway. The final report will be published on the institute’s website at some point in the future, and we encourage you to refer to the report when it is published.

About the questionnaire survey

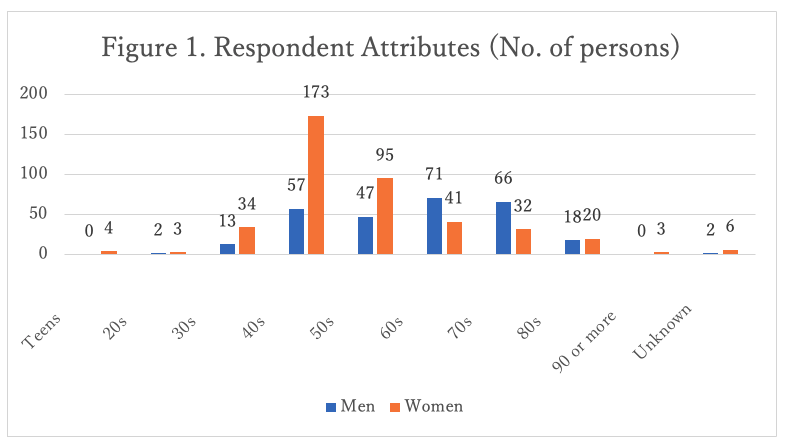

The “Nationwide Survey of Evacuees from the Nuclear Accident” was distributed in July 2020 with the cooperation of a number of life reconstruction support bases. In addition, many individual inquiries were received, as it was also sent out from the institute’s social media account. Other evacuees who had not been counted in the past, such as evacuees from prefectures other than Fukushima Prefecture and evacuees who were not registered in the National Evacuee Information System, also expressed their desire to cooperate. As a result, 694 responses (a 14% retrieval rate) were received. 75% of the respondents were evacuees from Fukushima Prefecture, and 18% were from the Kanto region.

Of these respondents, 100 (14%) had lived before the earthquake disaster in what are now difficult-to-return zones, 140 (20%) had lived in areas where evacuation orders have been rescinded, and 417 (60%) lived in areas where no evacuation orders were issued (referred to in this article as evacuees from outside designated evacuation zones). Thus it is clear that many respondents were evacuees from outside designated evacuation zones.

Characteristics of Evacuees from Difficult-to-Return Zones and Zones where Evacuation Orders have been Rescinded

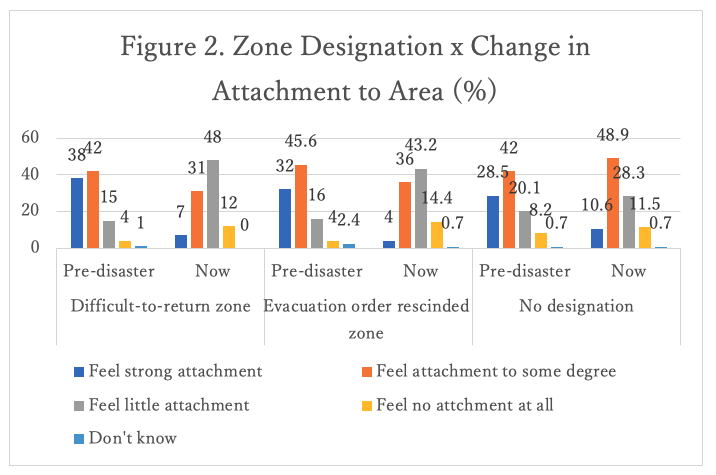

Respondents were asked about satisfaction with their “job,” “place of employment,” “income,” “leisure time,” “housing,” “local environment,” “educational environment,” “natural environment,” “public facilities in the city,” “places for cultural activities,” “places for sports activities,” “shopping convenience,” “convenience of medical facilities,” “transport convenience,” and “life in general” before and after the earthquake. As a result, “satisfied” and “slightly satisfied” showed a marginal increase for “shopping convenience” and “transport convenience,” but at the same time, “dissatisfied” and “slightly dissatisfied” also increased. In all other items, “dissatisfied” and “slightly dissatisfied” with the current situation increased. The results indicate that many evacuees felt their situation had been better before the earthquake disaster. In addition, and similarly, the degree of attachment to the area of residence also declined. In particular, many evacuees from difficult-to-return zones and zones where evacuation orders have been rescinded believed they were evacuating from their homes only “temporarily.” The average number of years of residence in the pre-disaster residence is also large. As most of the respondents from the difficult-to-return zones and zones where evacuation orders have been rescinded were in their 60s and 70s, it was clear that it was no easy matter for these elderly people to move to a new residence due to the sudden nuclear accident and become attached to the new area. Figure 2 shows the results of the degree of attachment to the area of residence of evacuees from the difficult-to-return zones, the zones where evacuation orders have been rescinded, and from outside designated evacuation zones before and after the earthquake disaster. 38% of respondents from difficult-to-return zones felt a strong attachment to the area where they had previously lived, with 42% feeling a certain degree of attachment, while a mere 7% now feel a strong attachment, with 31% feeling a certain degree of attachment; a significant decrease. On the other hand, evacuees who felt or feel little attachment to their areas increased from 15% before to 48% after the earthquake disaster.

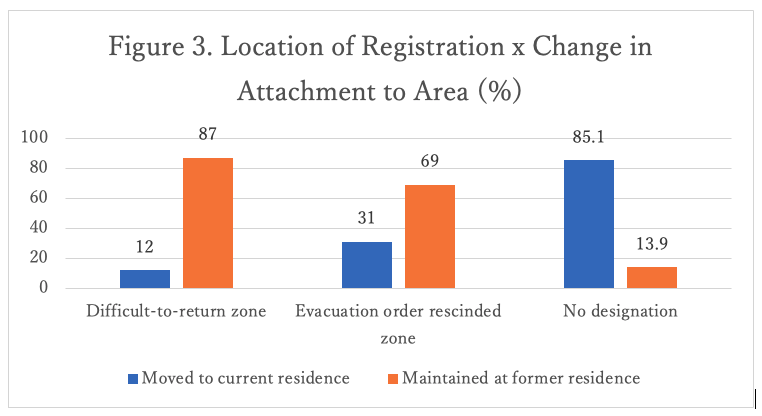

It was also found that many evacuees from difficult-to-return zones and zones where evacuation orders have been rescinded have maintained their original homes as their registered address (Figure 3). 87% of evacuees who had lived in difficult-to-return areas maintained their original addresses, while 85.1% of evacuees from outside designated evacuation zones had moved their registration to their current address; a substantial difference.

In reality, however, as shown in Figure 4, 63% of the former residences in the difficult-to-return zone have been left as they were after the disaster, and 14% have become vacant lots. 40% of the former residences of evacuees from zones where evacuation orders have been rescinded have become vacant lots, and 14% have been left as they were after the disaster. The evacuees have maintained their registrations at their former homes due to the Act on Special Measures for Evacuees from Nuclear Power Plants, but the reality expressed by the respondents was that “I want to go home, but can’t.” This leads to the conclusion that 65% of people who have evacuated from Fukushima have no intention of returning home.

Allow me to quote from one of the free prose responses of those who evacuated from the difficult-to-return zones. “I want people never to forget the first nuclear power plant accident in Japan for the rest of their lives. I want them to know how hard it is to lose everything from the places they were born and raised and to go and live in another prefecture. It’s not just about money.”

Characteristics of Evacuees from Outside Designated Evacuation Zones

This section concerns the characteristics of evacuees outside the designated evacuation zones. While many evacuees from evacuation zones who temporarily evacuated in accordance with government instructions evacuated to neighboring prefectures such as Ibaraki or Miyagi, a large number of evacuees from outside designated evacuation zones responded from Nagoya or areas further west or from Hokkaido. It was found that individuals and their families who had little option but to evacuate at their own discretion evacuated to locations far from the nuclear plant.

It was also revealed that the splintering of households was intensified by the evacuation. When asked about co-habitants, 4.3% of the respondents selected “Unmarried children only” before the disaster, while that figure is currently 16.4%, a 3.8-fold increase. On the other hand, those who chose “my parents or spouse’s parents” decreased from 7.1% before the earthquake to 2.9% at present, and those who were living as three-generation households also decreased from 10.8% before the earthquake to 4.5% after.

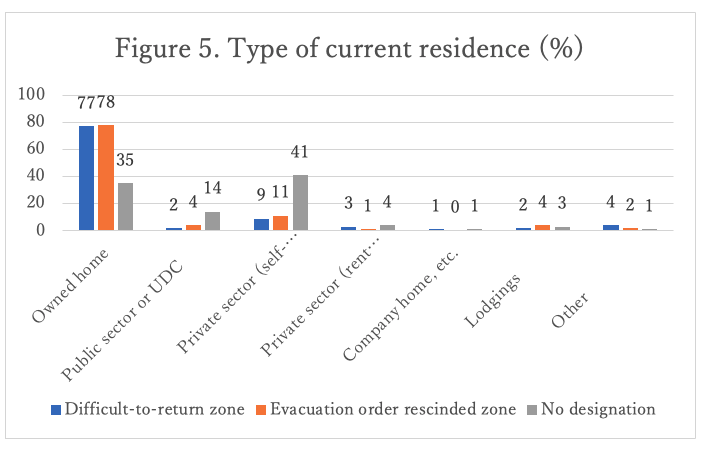

Furthermore, looking at the types of residences at evacuation destinations (Figure 5), it can be seen that the proportion of evacuees who had lived outside designated evacuation zones renting housing (the total of public sector, public, Urban Development Corporation and private rented houses) is close to 60%.

Concerning whether or not evacuees from outside the designated evacuation zones have received housing subsidies, 60% responded that they have not. It is presumed that, amid the confusion at the time of the earthquake, staff at the municipal office contact points either did not understand the situation or simply did not receive information about evacuees.

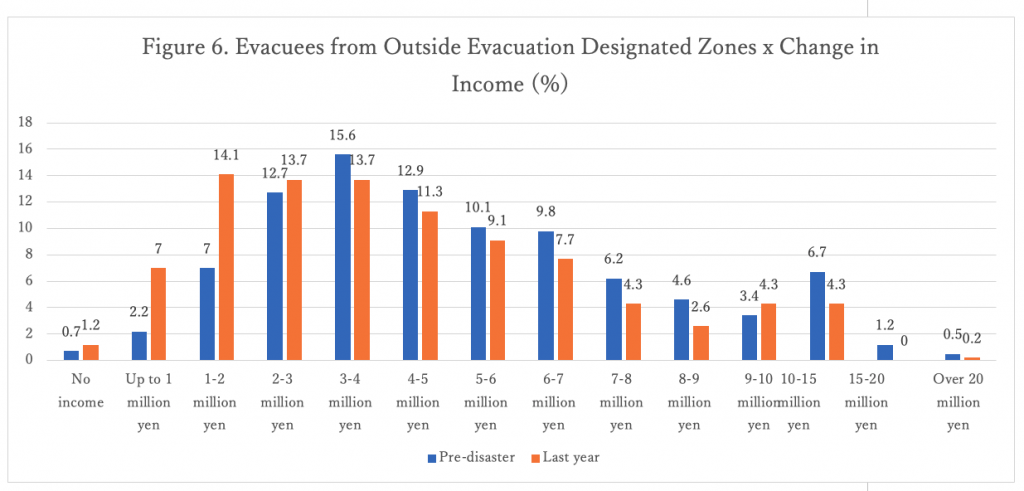

Additionally, evacuation has resulted in changes in occupations, and changes in income associated with occupational change. As shown in Figure 6, people with an annual income of less than 1 million yen increased by 3.1 times after the earthquake compared with before, and those with an income between 1 and 2 million yen doubled from 7% to 14.1%. For many evacuees, the evacuation thus resulted in a shift toward lower incomes.

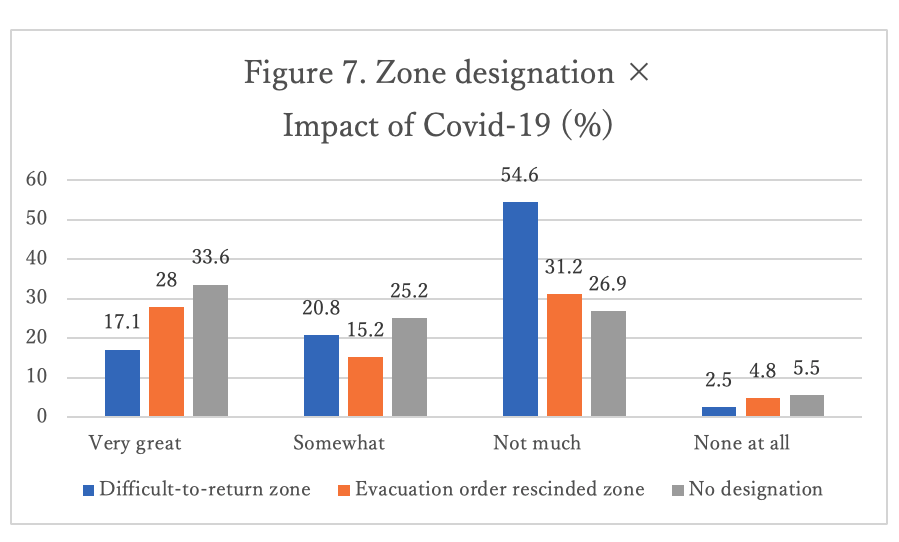

The Covid-19 pandemic also greatly affected the situation of evacuees from outside designated evacuation zones (Figure 7). The lower the income, the more evacuees were affected by Covid-19, 58.8% of evacuees from outside designated evacuation zones responding that they were either “very seriously affected” or “somewhat affected.” 20% of the respondents replied that the impact on their monthly income exceeded 100,000 yen.

Regarding the special flat-rate benefits distributed to all households, one respondent was told, “You have no right to receive the benefit because you evacuated despite opposition from your family.” It was also found that problems occurred due to the system providing benefits to heads of households rather than to individuals, such as in the response, “The head of the household received the benefit, and therefore I haven’t received it.”

107 women responded that they were currently living with their “unmarried children only” (mother and child(ren) evacuation), of whom 96 were evacuees from outside the designated evacuation zones. When asked about the degree of relations with neighbors, the number of these respondents who said they “have a close friend who helps out when I have a problem” decreased from 51 before the earthquake to 22 after. Those who replied that they “have little contact with neighbors” increased from 3 to 23. It is possible that these evacuees are estranged from their neighbors due to evacuation to an urban area from their pre-earthquake locations. This was not so serious if people could engage in mutual assistance through a different network that substitutes for contact with their neighbors, but evacuees who were not embedded in such a network are in the most serious situation. When asked in the next question about their anxieties and worries, the most frequent response was “my family” (27%), followed by “the support center” (17%). The role of the support center, which is able to provide a variety of consultation services, including for minor daily consultations, is crucial and it is thought that support centers will become even more important in the future.

Of the respondents who evacuated from outside designated evacuation zones, 69 were divorced, bereaved or separated women living with unmarried children, accounting for 10% of all respondents. Junior high school students account for the largest number of these children, followed by elementary and high school students. We can see that children were being evacuated while still quite young. (In fact, the most common reason for evacuating from outside designated evacuation zones was “Because I wanted to protect my child(ren)’s health” (72.2%, multiple responses)).

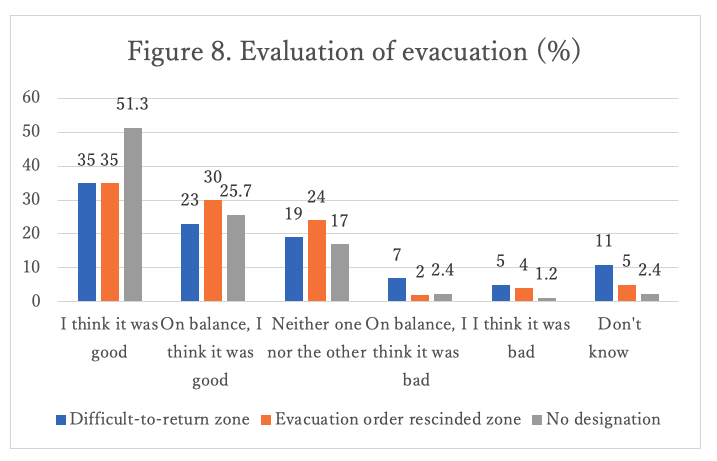

Due to this, 77% of the respondents gave the response to how they evaluated their evacuation as “I think it was good that we evacuated” or “on balance, I think it was good that we evacuated,” which shows a tendency to be higher than the evaluation given by evacuees from inside the designated evacuation zones (Figure 8).

In response to the question why have you not returned to your former residence, the most common responses were “The radiation air dose rate has decreased, but it seems that there are still areas such as forests and grasslands that are contaminated.” (52.8%. multiple responses), “because we have now settled in our current home” (44.8%), and “We don’t know what might happen at the nuclear plant, where decommissioning is now taking place.” (44.7%). Many people have a deep mistrust regarding the nuclear power plant and feel that the situation makes it impossible for them to return home.

As stated in an evacuee’s free prose response, “For the children who now have their daily life here, it has been a ten-year struggle to build this existence. We can’t start all over from scratch again,” it was found that many evacuees felt that it would be very difficult to move again and re-establish their former relationships.

Summary

Ten years have passed since the Great East Japan Earthquake, and in the face of this latest threat from the Covid-19 pandemic, the memories of past disasters are already fading from people’s minds. This survey, however, shows that the “human recovery” of long-term evacuees is far from complete, and various problems still remain. Evacuees who wrote “We’re OK now” in the free response column (though you would have to go and see them if you wanted to find out if they were really OK or not) and evacuees who wrote “We’re having a hard time” cannot simply be lumped together. Each person has had his or her own experiences of the past ten years, and, of course, life goes on. It is certainly not acceptable that necessary assistance should be discontinued after ten years have passed.