South Korea’s Climate Justice Movement Challenges Insidious Governance Strategy with Diverse Tactics

By Takano Satoshi, Ph.D. Candidate, Graduate School of Environmental Studies, Seoul National University

The Moon Jae-in administration, by encouraging public debate on nuclear power policy in 2017, has reached a decision on a “nuclear phaseout” by 2083, scrapping plans to build new nuclear power plants (NPPs) and banning extensions of design lifetime, although the ongoing construction of the New Kori Units Nos.5 and 6 will continue. As a result, the social question of nuclear power has come to a halt, and while issues remain, such as dry-reprocessing technology, the development of small modular reactors, and the bringing forward of the fiscal year in which nuclear power generation will end, the anti-nuke movement, suffering from being made into a political issue, has stagnated. Against this backdrop, attention on energy issues has shifted to the climate crisis. While also touching on nuclear issues, I would like here to analyze the climate justice movement in South Korea, which has been showing an upsurge recently.

The 2050 Carbon Neutral Declaration and the Carbon Neutral Commission

In a speech to the National Assembly in October 2020, the Moon Jae-in administration declared carbon neutrality by 2050. In December, the administration prepared a scenario and announced the establishment of a Carbon Neutrality Commission (CNC) as a consultative body. It also said it would reset the 2030 NDC (Nationally Determined Contribution, the national greenhouse gas reduction target), a 26.3% reduction from 2018 levels, to a more ambitious target. In January 2021, a “technical working group” consisting of experts recommended by 11 relevant government departments was established and practical work for scenario preparation begun, resulting in a plan being presented in June. Immediately prior to that, on May 29, CNC was formed as a commission under the direct control of the Office of the President. CNC consists of 97 members, including 19 ministers from relevant government departments and 78 members who are experts in climate, energy, industry, labor, and education, as well as members from a wide range of sectors and social levels, including civic groups, youth groups and local governments. As chairpersons of the committee, the prime minister was elected for the government side and a Seoul National University professor was elected for the civic side.

Three Draft Scenarios and the Process for “Building a Social Consensus”

CNC presented three 2050 draft scenarios on August 5, after about two months of discussions. Proposal 1 is a scenario in which seven coal-fired thermal power and LNG plants remain in the power generation sector, emitting 25.4 million tons of greenhouse gases; Proposal 2 is a scenario in which coal-fired thermal power plants are totally abolished but LNG plants remain, emitting 18.7 million tons of greenhouse gases; and Proposal 3 is a scenario in which the power generation sector achieves zero greenhouse gas emissions and zero net emissions by totally abolishing thermal power plants. Proposals 1 and 2 state that net emissions, which are total emissions minus any domestic sinks such as forests or reductions due to CCUS (carbon capture, use and storage), would occur in the form of emissions of greenhouse gasses, but these would be offset by overseas afforestation projects and international carbon markets.

On August 7, after the scenarios were presented, a Carbon Neutral Citizens’ Conference was organized to reach a social consensus through deliberations by the general public. About 500 citizens over the age of 15 were randomly selected for the citizens’ conference, and after e-learning and lectures by experts, small group discussions on some issues and a question-and-answer session with the experts were held on September 11-12, and a survey was conducted to examine shifts in opinions. Introducing some of the results, a majority, 55.2%, of the citizens said that carbon neutrality should be achieved before 2050. On the other hand, regarding the closure of coal-fired plants, the largest proportion of the citizens, 30.8%, said they would shut down coal-fired thermal power plants by 2050. This appears at first to be a contradictory response, but it can be interpreted as a mixture of people’s demands for consideration for the employment of coal-fired plant workers and a bold net-zero policy. In the final survey, 76.5%, up from 66.2%, supported the idea of gradually phasing out nuclear power as a means of achieving carbon neutrality. These survey results are to be reflected in the preparation of the final scenario.

After collating all the opinions, CNC approved the 2030 NDC and the final 2050 carbon neutral scenario on October 18. The 2030 NDC was reduced by 40% from the 2018 level, and the main power source mix was 24% for nuclear power, 22% for coal, and 30% for renewable energy. The plan also includes measures to maximize carbon emissions reductions outside the country and the use of carbon markets.

For the final 2050 carbon neutral scenario, two proposals were presented. In Proposal A, thermal power generation was totally abolished, and the power source mix was 6.1% for nuclear power, 71% for renewable energy, and 21.5% for carbon-free gas turbines. Proposal B preserves only a small amount of LNG, being 7.2% for nuclear power, 5% for LNG, 61% for renewable energy and 14% for carbon-free gas turbines. The CNC chairperson announced these results to the world when she participated in the Glasgow COP 26.

Strategies of Diverse Climate Justice Movements Protesting the CNC

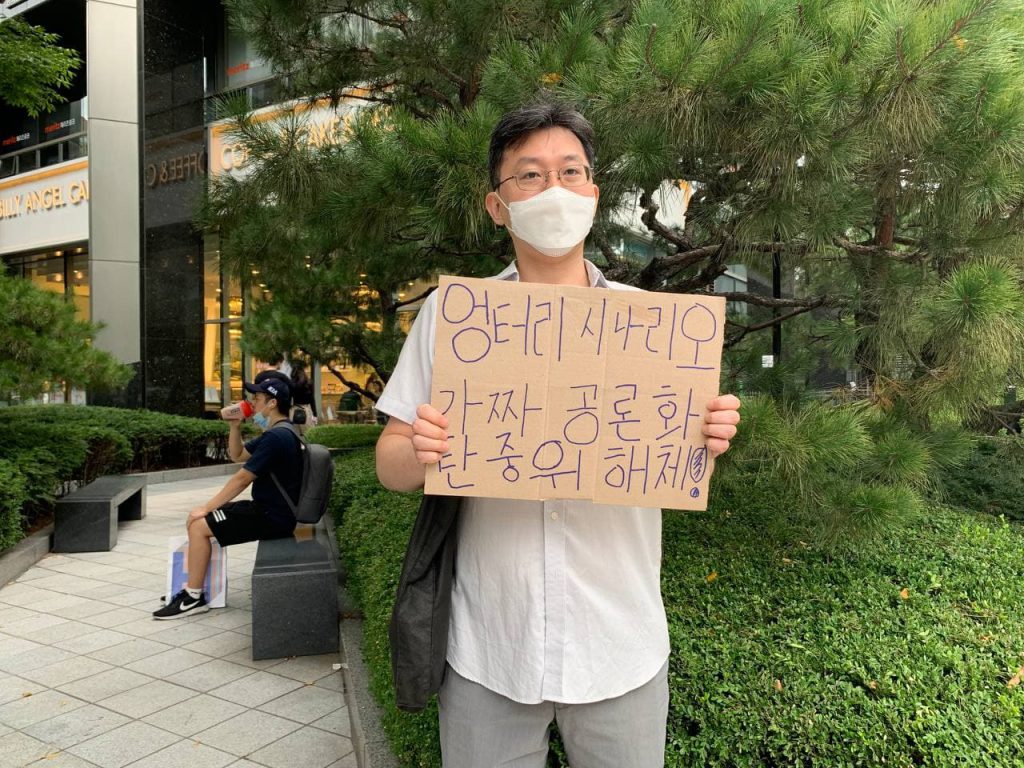

Let’s take a look at the social movements’ responses to the CNC consultation process. After the three scenarios were presented, climate justice groups began to take action to criticize their inadequacy. Climate Crisis Emergency Action, formed in August 2019 and representing a network of more than 300 climate justice groups, organized online gatherings and discussion meetings. As some of the organizations had members who had become CNC members, they did not insist on dissolution of CNC, but demanded a 50% reduction in the 2030 NDC and climate change measures grounded in climate justice. A more radical demand was made by the Joint Countermeasure Committee for the Dissolution of the Carbon Neutral Commission and the Realization of Climate Justice (hereafter, JCC). After the three scenarios were presented, JCC was formed on September 2 as a temporary network of about 50 groups and individuals, including the author, seeking dissolution of CNC. From September to October 18, when the scenario was passed, members of JCC held a one-person demonstration each day in front of the building where CNC was located. Even in the situation where only one person could take part in a demonstration because of the pandemic prevention measures against COVID-19, group demonstrations with an interval of about five meters between each demonstrator were implemented despite police demands for disbandment and the threat of fines. In terms of policy, JCC called for cuts based on the carbon budget1, the upper limit of greenhouse gas emissions allocated to South Korea to limit the temperature rise to 1.5°C by 2050, and called for the suspension of coal-fired thermal power generation by 2030. The CNC scenario, which calls for active use of CCUS, and in which industry, which emits the largest amounts of CO2 but whose emissions reductions are low, is nothing more than a strategy to lighten the responsibilities of capital and corporations. The public debate was therefore criticized by JCC as being an irresponsible stratagem.

Young people are also active in the movement. A group of 12 young people’s organizations, composed mainly of young people in their 20s, created a 2040 Climate Neutrality Scenario, which aims to achieve net-zero by 2040. Some of the members participated as members of CNC. These young people met with the CNC chairperson and requested that a scenario based on the carbon budget be developed and that their own scenario be adopted. Although this was rejected, the 2040 Climate Neutrality Scenario was presented as an official government document along with the CNC scenario. One of the members of the Youth Climate Action, consisting of even younger people, in their teens, became a CNC member, but was dissatisfied with the CNC’s insistence on demanding compromises against his emphasis on a fundamental transformation of the social system and announced her resignation before the commission ended. In her statement of resignation, she asserted that to continually demand compromise in the face of the serious problem of the climate crisis, and to block the voices of those concerned, was tantamount to a collapse of democracy. She also announced that she would hold a “Climate Citizens’ Assembly” to listen to the voices of people on the front lines of the climate crisis on issues such as food, housing, poverty, and labor, thereby aiming for a genuine public debate for the future that differs from that of the CNC.

Young people are also active in the movement. A group of 12 young people’s organizations, composed mainly of young people in their 20s, created a 2040 Climate Neutrality Scenario, which aims to achieve net-zero by 2040. Some of the members participated as members of CNC. These young people met with the CNC chairperson and requested that a scenario based on the carbon budget be developed and that their own scenario be adopted. Although this was rejected, the 2040 Climate Neutrality Scenario was presented as an official government document along with the CNC scenario. One of the members of the Youth Climate Action, consisting of even younger people, in their teens, became a CNC member, but was dissatisfied with the CNC’s insistence on demanding compromises against his emphasis on a fundamental transformation of the social system and announced her resignation before the commission ended. In her statement of resignation, she asserted that to continually demand compromise in the face of the serious problem of the climate crisis, and to block the voices of those concerned, was tantamount to a collapse of democracy. She also announced that she would hold a “Climate Citizens’ Assembly” to listen to the voices of people on the front lines of the climate crisis on issues such as food, housing, poverty, and labor, thereby aiming for a genuine public debate for the future that differs from that of the CNC.

However, the governance of CNC, which includes many civic groups, has had a serious impact on social movements. This is symbolized by the scenario decision on October 18. On that day, an emergency action on the climate crisis and protest action by JCC were held in front of the conference hall where CNC was to meet. However, the venue was tightly controlled by the police, the protests were suppressed, and several people were injured. Some activists shed tears over the reality of the social movement, divided between the inside and the outside of the police line, when they saw members of civic groups who were once their comrades calmly enter the hall under police protection. Looking back, how do we feel about the Japanese movement? Is it not a situation where everyone writes a public comment and falls into defeatist mannerisms when they are not reflected in policy and only sigh at each other? While suffering from insidious governance strategies, I hope we can cultivate the imagination for resistance of the Korean climate justice movement, which put pressure on CNC by using a wide range of tactics from both inside and outside.

However, the governance of CNC, which includes many civic groups, has had a serious impact on social movements. This is symbolized by the scenario decision on October 18. On that day, an emergency action on the climate crisis and protest action by JCC were held in front of the conference hall where CNC was to meet. However, the venue was tightly controlled by the police, the protests were suppressed, and several people were injured. Some activists shed tears over the reality of the social movement, divided between the inside and the outside of the police line, when they saw members of civic groups who were once their comrades calmly enter the hall under police protection. Looking back, how do we feel about the Japanese movement? Is it not a situation where everyone writes a public comment and falls into defeatist mannerisms when they are not reflected in policy and only sigh at each other? While suffering from insidious governance strategies, I hope we can cultivate the imagination for resistance of the Korean climate justice movement, which put pressure on CNC by using a wide range of tactics from both inside and outside.

*1) Carbon budget: The fixed amount of the upper limit of cumulative greenhouse gas emissions (past emissions + future emissions) in the case that it is attempted to limit the temperature rise to a certain level.