High-Level Radioactive Waste Symposium: “To Avoid Progression to the Overview Survey”

Participant Report

By Takano Satoshi (CNIC)

A symposium on high-level radioactive waste titled “To Avoid Progression to the Overview Survey” was held on November 4 in Otaru, Hokkaido. There were about 150 participants. I was also invited to attend and speak, the contents of which I would like to report here.

The Importance of Building Communities Non-reliant on Nuclear Money

First, Professor Emeritus Koda Kiyoshi of Hokkai-Gakuen University gave a presentation. Prof. Koda, together with the people of the Ganwu area, consisting of Iwanai Town, Tomari Village, Kyowa Town and Kamoenai Village, has been holding study sessions on how to build a community free from reliance on “nuclear money” (money from nuclear power). In his presentation, he described the content of these study sessions. The local industry most heavily impacted by nuclear power is fisheries. Hokkaido Electric Power Co. (Hokuden) has paid out 21.1 billion yen to fishermen thus far as compensation to fisheries and funding for community promotion. Iwanai District and the Tomari Village fisheries cooperative have distributed the compensation funds to individuals. This was done to help pay back debt incurred in purchasing larger boats, but it did nothing to help establish new industries locally.

Other benefits municipalities hosting nuclear power plants (NPP) receive are power source siting law subsidies and fixed asset taxes. Tomari Village has received a huge amount of fixed asset taxes, 64.7 billion yen to date, most of which is estimated to have come from the NPP. Moreover, Hokkaido overall has received 174.2 billion yen in nuclear money in various forms, such as nuclear fuel taxes.

So, has this nuclear money helped prevent depopulation of these towns? Not at all. In fact, they have experienced more severe population declines than other communities that have not been receiving nuclear money. In the Ganwu area, it is Kyowa Town that has had the lowest population decline. This is because Kyowa Town does not rely on NPPs, but has been striving for community development centered around primary industries, i.e., rice fields, watermelon and melon farms and other forms of agriculture. In contrast, the impact on Iwanai Town, centered around fisheries in the Ganwu area, has been enormous. In 1985, Iwanai Town had 706 people employed by fisheries, but in 2020, the number had fallen catastrophically to 68 people. This town’s devastation spotlighted the decline in fisheries of the district overall. Prof. Koda also described the effects of an NPP on local industries and public finances. Tomari Village’s construction industry flourished when the NPP was being built, but since that was completed, it has declined. On the other hand, he pointed out, electric power-related businesses, hotels and other service industries have flourished, and the composition of the local industries has changed. Regarding public finances, thanks to the enormous amount of fixed asset taxes, in 2020, Tomari Village’s financial capability index (standard financial revenues divided by basic fiscal demand) was 1.58, even higher than Tokyo’s. Meanwhile, the financial capability index of Kamoenai Village, which does not receive fixed asset taxes, is a tiny 0.11. This is explained mainly by the big effect fixed asset taxes have on public finances. Prof. Koda also noted that with wind power facilities, Suttsu Town should be thriving, but its index is no higher than 0.14, and the reasons for that will be a subject for future research.

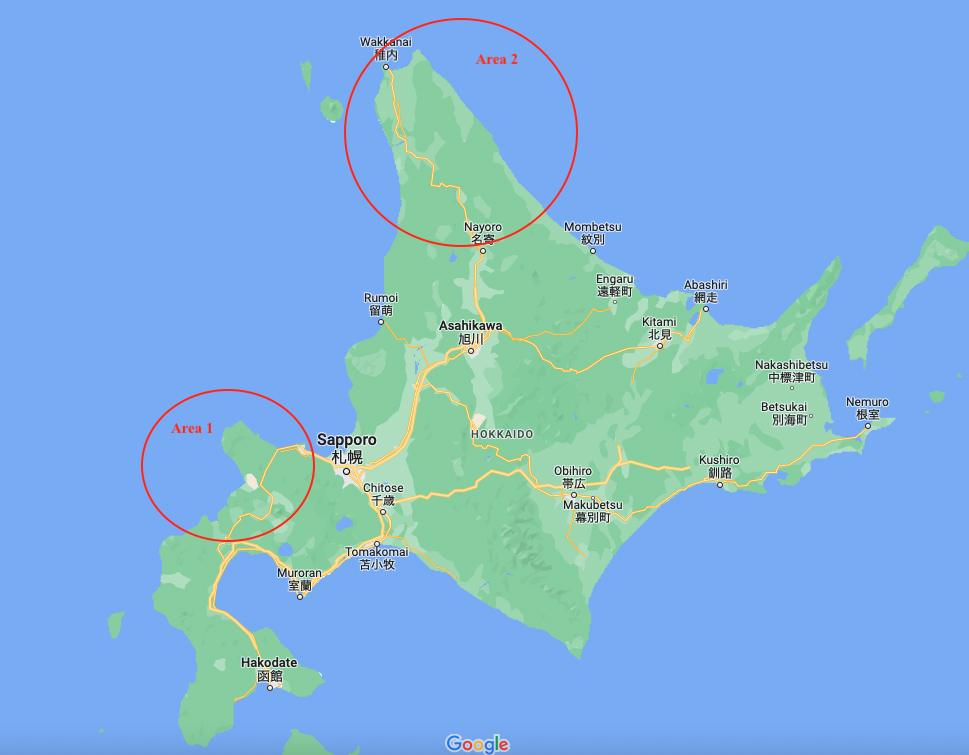

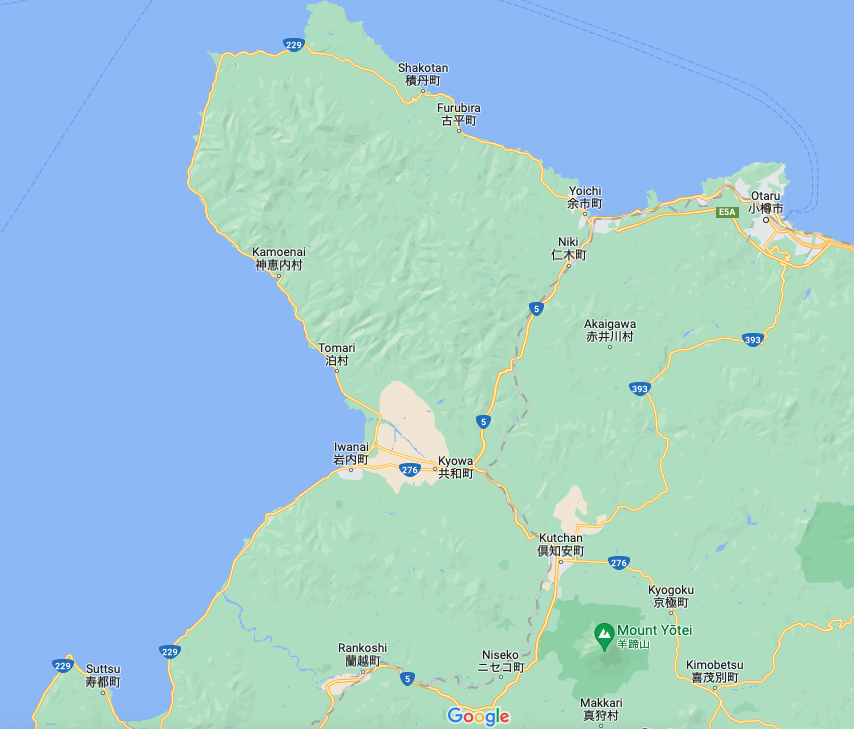

What is important is the fact that nuclear money cannot rescue a municipality from the clutches of depopulation and the idea of building communities anew to prevent depopulation. Prof. Koda gave the example of Otoineppu Village (see map of Area 2), which undertook community building centered around the village high school. They established the Otoineppu Art & Craft High School specializing in industrial arts, and have accepted 115 students, all from outside the village. As all students live on campus, this generates demands for dining hall and other services. The village’s population continues to decline bit by bit, but it has managed to thrive without merging with other municipalities.

Prof. Koda also noted that teaming up with neighboring areas is important too. Suttsu Town has found community building on its own to be difficult. Ideas are needed for spreading the tourist attraction effects of the Niseko ski resort area throughout the Shiribeshi area overall. Or regarding the flow of people from Shin-Chitose Airport and Sapporo to destinations like Otaru and Yoichi, there is a need to consider ways to increase the scope of sightseeing by this kind of tourist from outside the region. The problem with accepting the literature review is that it results in divisions not only within the Suttsu area, but also between it and adjacent areas. For example, the inter-community cooperation that is necessary for plans to construct offshore wind power facilities has also been affected because of Suttsu’s acceptance of the literature review. Prof. Koda contended that there is no future in community building if it relies on subsidies.

Nuclear Money Robs Citizens of Their Autonomous Spirit

Sato Hideyuki, who chairs Tomari Genpatsu Ritchi 4 Choson Jumin Renraku Kyogikai (citizens’ liaison council of the four towns and villages hosting the Tomari NPP), commented on nuclear money. Chairman Sato has been participating in Prof. Koda’s community-building study sessions as an Iwanai Town resident. He said that in addition to its effects on Iwanai Town’s fisheries, nuclear money has had psychological effects on the community’s residents. He said he had come to see that in reality nuclear money had pushed local industries to the brink of ruin, with economic ripple effects and local governments launching subsidy offensives, leaving local citizens in thrall to nuclear money and making it impossible for them to say anything. Once an NPP starts operations, the problems it causes are not dealt with until later and inevitably snowball. He also warned that nuclear money kills people’s normal ability to enact changes in current realities for a better future.

Matters Elucidated by History of Horonobe’s Battle against Nuclear Garbage

Azuma Osamu, who co-chairs Dohoku Renraku Kyogikai (northern Hokkaido liaison council), which opposes the invitation of nuclear waste disposal facilities, spoke about the battle against nuclear garbage in northern Hokkaido. Co-chairman Azuma currently resides in Wakkanai. He has led the movement opposing nuclear garbage in Hokkaido, which is centered around Horonobe, where the Horonobe Underground Research Center* is located. Looking back on the 38-year history of the battle against nuclear garbage that began in 1984 in Horonobe, he pointed out in his presentation two ways in which the situation has worsened in recent years. The first is that although there were no plans for drilling, work began on a 500-meter mine shaft, 150 meters deeper than the existing shaft in FY2020. The second is that NUMO (Nuclear Waste Management Organization), which is in charge of Japan’s geological disposal, started considering participating in research at the Horonobe Center in FY2021 in the form of joint international research in Horonobe. Azuma explained that in light of the Hokkaido ordinance pledging not to accept nuclear waste and the Tripartite Agreement between Hokkaido, Horonobe and Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) prohibiting the transfer or loan of the facilities to NUMO, this is an extremely serious problem. Nonetheless, Hokkaido and Horonobe Town have given their formal approval for these plans. Considering the history and current progression of matters, there is an increasing sense of crisis that Hokkaido’s ordinance may be scrapped.

The Need for a Joint Strategy against Nuclear Garbage

The author also spoke, describing his experience as a member of the Working Group (WG) on Radioactive Waste and suggesting how the movement could respond in the future. I pointed out that progress in the Radioactive Waste WG’s discussions has been hampered by some of its policies promoting nuclear power, because its secretariat is under the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, which is promoting nuclear energy. In fact, since all of its members are appointed by bureaucrats, a large number of them are happy with the existing policy framework of reprocessing all spent nuclear fuel and dealing with wastes through geological disposal. Furthermore, the secretariat holds all the authority for setting dates of meetings and topics for discussion. I lived in Korea for a long time and can say that a situation like this, in which fair competition is impossible from the start, is described there as a “tilted playing field.” In other words, the policy-making process is distorted from the start, and there is no guarantee of impartiality. What is important, I explained, is that a keen critical awareness is needed of the structural imbalance in the Radioactive Waste WG and efforts must be made to rectify it. It is not enough to take easy steps such as presenting correct arguments to be recorded in the minutes.

So, how can we reform it? Of course, this is a difficult and time-consuming problem to deal with. First, I explained, we need to create a tighter federation among everyone involved in the movement against nuclear garbage and meet with each other regularly to share information. Under such a network organization, I would urge for constant monitoring of the WG and other administrative processes, and for developing joint strategies for actions such as issuing protest statements immediately upon detecting problems, appealing to people on the street and in the media and working with residents’ organizations that are opposed to nuclear garbage. Without that kind of joint strategy, it would be difficult to try to open up the government’s exclusive policy-making processes for nuclear waste, and the government would probably just continue legitimizing its policies.

————————–

*Under JAEA’s jurisdiction.