CNIC Statement: Opposing Revisions to the Basic Policy on the Final Disposal of ‘Nuclear Garbage’

16 February 2023

The Kishida Administration held a ministerial meeting on final disposal of nuclear waste on February 10, 2023, announcing revisions to Japan’s basic policy on the final disposal of specified radioactive wastes. Based on the Act on Final Disposal of Radioactive Wastes, this basic policy determines the fundamental orientation of Japan’s policies on high-level radioactive waste disposal. Prime Minister Kishida Fumio issued a directive on December 22, 2022 at the GX Implementation Council meeting to expand the target area for the government to conduct “literature reviews,” (the first step a municipality makes to put up its hand to host a radioactive waste repository) and that is to be brought about by revising the basic policy. The revised plan was revealed at the ministerial meeting. Public comments on it are being accepted until March 12.

The content of the revisions is, to put it simply, acceleration of the final disposal site selection process. To achieve that, three main measures will be employed. The first is to create a system linking the relevant ministries and agencies with each other. Specifically, the government is establishing a “liaison council for relevant ministries and agencies” and a “liaison council for local branch offices,” and will be offering consultation on local development to areas applying for the literature review and local public organizations showing an interest in it. In other words, they will discuss the provision of support in related fields in accordance with local interests and needs, making maximal use of regional measures, grants, etc. to areas providing potential sites. Moreover, they will not just wait for people to come and consult with them, but will form a joint team consisting of the national government, NUMO (Nuclear Waste Management Organization) and the electric power companies and go around to individual local public bodies and relevant organizations throughout Japan, making a stronger effort to appeal to them.

The second measure is to create new venues for discussions between the national government and the relevant municipalities. The national government will bring together local governments that are interested in applying for the literature review but aware of issues related to actually applying, and through these venues, they will discuss and examine these issues and how to respond to them so that final disposal repository can be realized.

The third measure is to gradually step up propositions from the government to localities showing interest. This means the government will ramp up its proposals and suggestions to relevant local bodies such as economic organizations and councils to consider going along with a literature review in any community that has expressed any interest in it, starting from prior to the community’s decision to accept a literature review.

We at Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center (CNIC) are voicing our opposition to these revisions in Japan’s basic policy to accelerate the selection process. The reason for our opposition is that Japan’s high-level radioactive policy is based on false assumptions. The Act on Final Disposal of Radioactive Wastes has as its purpose “improving the environment in association with nuclear power for electric generation,” and NUMO, the entity in charge of the project, says that work toward final disposal is being done “to contribute toward the proper use of nuclear power.” In other words, the process of selecting disposal sites is associated with promotion of nuclear power. No social agreement has been reached, however, regarding the continued use of nuclear power for electric generation. Furthermore, it is plain from the current state of the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant in Aomori Prefecture, the operation of which was postponed for the 26th time in 2022, that Japan’s final disposal policy, which is to reprocess all spent nuclear fuel and vitrify it, is untenable. Despite this fiasco that the nuclear fuel cycle has become, this policy is being maintained unchanged. Even regarding geological disposal, there has been a lack of extensive pro and con discussions on it by experts, and no agreement can be said to have been reached here either. If they take a policy that has not been agreed upon and is based on faulty assumptions and promote it more vigorously than ever, anyone can see that the result will be to alienate society more profoundly than ever.

Moreover, if grants are used as a stepping stone to strengthen intervention locally, as the revisions are doing, there is a higher likelihood that heads of government or certain groups seeking grants will unilaterally force communities to accept promotion of literature searches. If that happens, divisions within these communities will inevitably be deepened and accelerated. In fact, when Suttsu Town, Hokkaido applied for a literature review, a schism arose there. CNIC staff have visited Suttsu Town numerous times, and have heard the town’s residents express strong opposition to NUMO’s intervention in the town’s development because NUMO was discussing the use of grants. Accelerating the selection process in the current situation would mean accelerating schisms in local communities. The government and NUMO must not repeat the mistake they made in Suttsu Town.

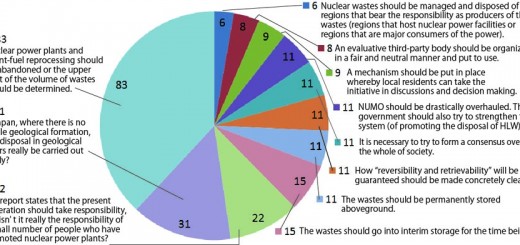

What the government should do is to take the lesson from Suttsu Town deeply to heart, not accelerate the selection process, but rather discontinue it. In addition, the government should revert to the proposal indicated by the Science Council of Japan in 2012 in its report on high-level radioactive waste disposal. Points raised within that report include interim storage and regulation of the total amount of spent nuclear fuel, reexamining the use of monetary measures for inducement, and step-by-step discussions by third-party organizations. The government needs to establish a highly independent public forum for comprehensive discussion of nuclear waste policy during the period of long-term interim storage. It is not right to promote selection of final storage sites without making efforts to promote participation and careful deliberation by citizens and stakeholders or establish an impartial policy-making process that is highly transparent and open to the public. More than anything, for the current generation to fulfill its responsibilities it must settle on policies that do not increase nuclear garbage beyond what has already been produced. That means giving up the nuclear fuel cycle and getting rid of nuclear power.