Fukushima Now Part 1: Railroading the Contaminated Water Release is Unacceptable!

By Ban Hideyuki (CNIC Co-Director)

The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) and Tokyo Electric Power Holdings (TEPH) had decided on a policy of oceanic release of the contaminated water, which continues to build up at Fukushima Daiichi NPS, from an early stage and have been steadily proceeding with preparatory construction work for the release. This work has been proceeding despite written commitments to the National Federation of Fisheries Cooperative Associations and Fukushima Prefecture Federation of Fisheries Cooperative Associations in August 2015 that “(contaminated water) would not be released into the ocean without their agreement.”

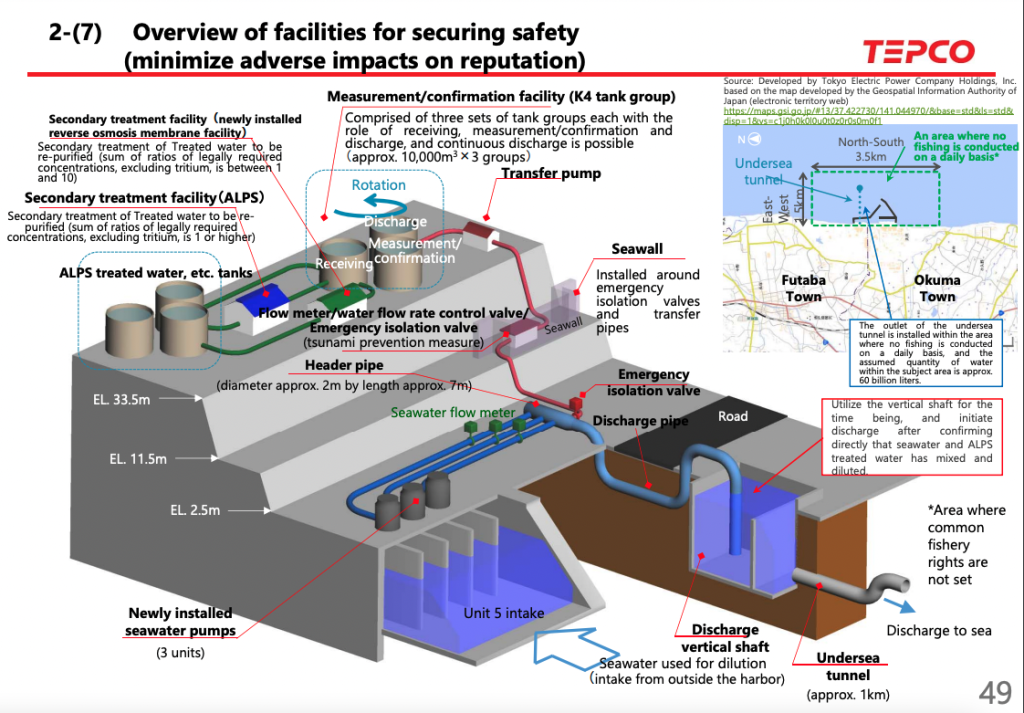

This is the plan for how the release work will proceed. Three groups with 10 tanks in each group are prepared. An agitator is placed at the bottom of one tank in each group and circulated around the 10 tanks to “homogenize” the contents. The amount of tritium is then measured to determine the volume of seawater it would need to be mixed with to result in a radiation level of 1,500 Bq/L. The current average concentration is estimated at about 600,000 Bq/L, meaning that, on average, the water would have to be diluted by a factor of 400. At the same time, a check is conducted to ensure that other radionuclides present in the water do not exceed the standard. ALPS processing is repeated until the standard is cleared. The seawater used for dilution is pumped up through three lines. The volume of seawater for dilution is adjusted by the rotation rate of these pumps. The contaminated water is released by group, taking about two months to release each group. The maximum volume of treated (contaminated) water diluted per day is 500 m3, which means that, according to the average dilution mentioned above, the average daily volume released is 200,000 m3. The annual release of tritium will amount to 22 trillion becquerels or less, which is the maximum release before the accident. Tunnel construction using boring machines began in August 2022 and had progressed to about 80% of the total distance of 1 km as of February 2023. The initial plan was to release the contaminated water from the coast, but this was changed to releasing the water from the seabed 1 km offshore and 12 m below the surface, presumably because it was thought that coastline pollution could not be ignored.

This resulted in construction costs of 43 billion yen for the first four years and a release period of 30 years or more, a significant increase from the initial estimate of 3.4 billion yen and 88 months. However, the cost is based on an assessment of 800,000 tons, which differs from the current volume, but nevertheless the assessment that the oceanic release method is “cheap and fast” has been destroyed. Fishermen’s groups passed a special resolution at their general meeting in FY2022 to oppose oceanic releases, and their opposition remains unchanged.

In response, METI raised a fund of 30 billion yen in November 2021 to deal with adverse publicity. The idea was to temporarily buy up seafood products whose demand had fallen and support them through online sales and other measures. However, perhaps because they realized this would be insufficient, they added a new fund of 50 billion yen in the FY2022 supplementary budget. According to media reports, “The money is expected to be allocated to the support of fishing boat fuel costs for fishermen nationwide.”

It is thought very unlikely that fishermen’s groups will change the way they see the ministry’s stance.

Securing storage space for high integrity containers is a challenge

Wastewater collected during the ALPS treatment and its pre-treatment stage is stored in polyethylene high integrity containers (HICs). As of December 2022, there were 4,192 containers in storage. To prepare for an increase in wastewater, TEPH plans to expand the storage space by 192 units by June 2025 and a further 192 units by about the middle of 2026.

As of June 2021, the Nuclear Regulation Authority had pointed out that there were 31 HICs with absorbed doses that had reached the limit of five mega-grays. That means the limit has been reached sooner than TEPCO had predicted, because, unlike TEPH, TEPCO evaluated absorbed doses from the sludge accumulated at the bottom of the waste effluent HIC. Thus, TEPH plans to extract the waste liquid from the HIC, dehydrate and solidify it by the filter press method, and set up “slurry stabilization treatment equipment” for that purpose. Test operation of the facility is scheduled to begin in mid-FY2026. According to TEPH, as of 2021, there were 23 HICs with excess absorbed dose levels generated per month (it is said that the number will be reduced to 10 in the future, but the grounds for this are unknown). Given that contaminated water will continue to be generated in the future, it is likely that securing storage space will become even more difficult.