Will nuclear power plants survive the climate crisis?

Introduction to the Study Report on Nuclear Power Plants’ Vulnerability to Climate Change

By Matsukubo Hajime (CNIC)

Recently, some sectors in society are actively promoting nuclear power plants as a measure against climate change. This is because NPPs are regarded as not emitting CO2 during operation. Nevertheless, there are many other CO2-free power generation options.

A nuclear power plant requires about 20 years from the initiation of planning to the start of operation. There are a few plants that are authorized to operate for 60 years in Japan and 80 years in the U.S. Plant decommissioning takes 30 years or so. Depending on the case, it is necessary to consider social circumstances for 130 years to come to run an NPP. Further, when the management of spent nuclear fuel is counted in, hundreds of thousands of years should be considered.

As climate change is becoming severer, its influence over a long period of time is foreseeable to some extent. Many academic papers have been released about the influence on NPPs of abnormal climate due to climate change. However, in Japan, public attention is focused on their low CO2 emissions, and the impacts that climate change may have on NPPs rarely attracts attention. In consideration of these situations, Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center (CNIC) has established the Nuclear Power Plant Vulnerability to Climate Change Study Group, which has drawn up a report on the vulnerability of NPPs to climate change evident today, to see if NPPs can actually be useful as a countermeasure against climate change.

The Study Group includes Ayukawa Yurika (Professor Emeritus, Chiba University of Commerce; Director, CUC Energy Inc.), Kenichi Oshima (Professor, Faculty of Policy Science, Ryukoku University), Kawai Yasuro (Plant Engineers’ Group), Hasui Seiichiro (Professor, Department of Contemporary Social Studies, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Ibaraki University), and Matsukubo Hajime (Secretary General, CNIC). Yamaguchi Yukio (Co-director, CNIC) is also participating as an observer. This research was funded by the independent civil society fund act beyond trust as a fiscal 2022 subsidized project.

A PDF file of this report is available at the CNIC website (in Japanese only)

Summary of the report

Chapter 1 of the report compares current CO2 emissions from NPPs and other power sources to establish a baseline of the study, confirming that nuclear plants are not predominantly favorable. The chapter also provides a rough appraisal of the influence of climate change on nuclear power facilities, and establishes the proposition of the study, namely, using nuclear power as a power source entails a challenge in that the conditions enabling NPPs to operate need to be maintained for great many years to come.

Chapter 2 studies whether nuclear power can be effective as a climate change measure from the economic point of view. There are multiple power alternatives that can serve as climate change measures, and nuclear power is merely one of them. This chapter clarifies the notion that because taking measures against climate change is an urgent issue, cost-benefit performance and time-benefit performance are very important. Nuclear power generation, however, cannot be useful as a measure against climate change, because it is extremely expensive and too time consuming. This chapter also studies future CO2 emissions from NPPs. Currently, more than half of NPP CO2 emissions are from the front end, namely, generated in the fuel manufacturing stage, where the uranium enrichment process is the biggest source of CO2 emissions. However, when uranium resources become depleted and lower-quality uranium ores start to be mined, CO2 emissions in the uranium smelting process will also increase. Depending on the situation, CO2 emissions in this process may compare with those from LNG thermal power generation.

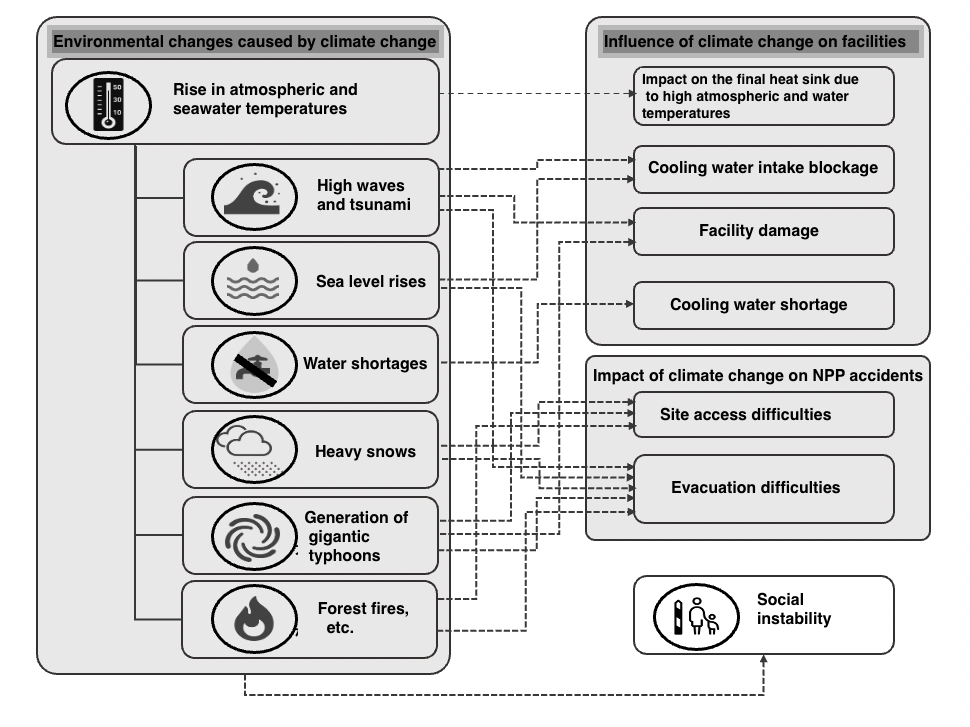

Chapter 3 discusses the influence of climate change on nuclear power safety. In other countries, after the Tokyo Electric Power Co. Fukushima Daiichi disaster, many studies have appeared that examine the viewpoint of whether nuclear power plants can resist extreme events related to climate change. In Japan, however, the consciousness related to the climate change crisis is low. What is learned from a literature review is that climate change may have an extremely serious influence on NPPs and bring about dangerous situations. As climate change is becoming serious, NPPs will halt more frequently. In addition, nuclear safety is susceptible to events related to climate change, such as sea level rises, higher water temperatures, and heavy winter snows.

Chapter 4 studies how the Japanese government’s new regulation standards established in 2013 after the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster stand against climate change. The standards demand only that the facilities should not lose safety functions under the maximum external impact estimated at the time of design, and do not consider future risks due to climate change except within current design margins. As unprecedentedly severe meteorological phenomena are becoming more frequent, the standards are precarious as a mechanism for guaranteeing safety.

Chapter 5 evaluates the effectivity of nuclear power plants from the standpoint of climate safety and security. The expression climate security has been in currency since 2005 or so. It encompasses a larger meaning than security as in national military security. For NPPs to operate as a measure against climate change, safe and stable operation is an essential precondition. As discussed in Chapter 3, the greater the influence of climate change, the more likely these preconditions will not be satisfied. Taking measures against climate change is an urgent issue; it is a challenge that will need to be grappled with for extended periods. If the attempt to make this challenge is handled only from the viewpoint of current power shortages, we will end up shouldering risks over a long period of time.