Foreseeing Japan’s nuclear future Nuke Info Tokyo No. 110

On 8 December 2005, Tohoku Electric Power Company’s Higashidoori-1 (BWR, 1,100 MW) commenced operations. With this new reactor, there are now 54 nuclear reactors in Japan, together having a total output of approximately 48 GW. In addition, Hokuriku Electric’s Shika-2 (ABWR, 1,358 MW) is undergoing trial operations, and Hokkaido Electric’s Tomari-3 (PWR, 912 MW) and Chugoku Electric’s Shimane-3 (ABWR 1373 MW) are under construction. Adding these reactors, the total capacity will come to approximately 52 GW.

Japan is third, after the United States and France, in terms of nuclear power output. Not counting those years in which significant numbers of reactors were shutdown due to accidents and so on, nuclear represent about 35% of the total electricity produced by electric power companies. The Atomic Energy Commission states in its Framework for Nuclear Energy Policy (14 October 2005), “…it is appropriate to aim at maintaining or increasing the current level of nuclear power generation (30 to 40% of the total electricity generation), even after 2030.” (p. 29)

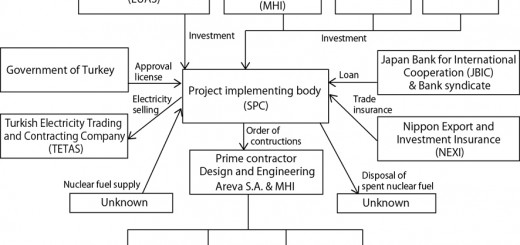

The Framework for Nuclear Energy Policy summarizes the direction of Japan’s nuclear power policy. In the past, equivalent documents were known as the “Long-term Program for Research, Development and Utilization of Nuclear Energy”. There was a controversy over whether the government should get involved in such specific planning and this led to the change of name from “Long-Term Plan” to “Framework”. More importantly, among the reference materials attached to the Framework, there is a graph entitled “mid-term direction” (Japanese version only, p. 91), showing a nuclear output of 58GW continuing from 2030 through to 2100.

|

|

Cartoon by Shoji Takagi

|

Nonetheless, considering that the 1994 “Long-term Plan” predicted that the capacity in 2030 would be 100GW, the figure in the revised plan is very moderate. The plan involves replacing old nuclear reactors. Since the output of replacement reactors is expected to be larger than that of existing reactors, the plan must have been drawn up based on the assumption that not every reactor will be replaced. However, even an output of 58 GW is highly unrealistic. More likely, by 2030 many reactors will have been decommissioned without a replacement being built. The net result of this would be a reduction in total capacity. If that happens, it will be impossible to sustain Japan’s nuclear power industry and there will be a swift and total phase-out of nuclear power.

As mentioned above, there are now 54 nuclear reactors in Japan. Yet there are only 17 nuclear power plants (NPP), some of which are located close to each other. The construction plans for all of these NPPs were announced before 1970. None of the construction plans announced since 1971 have resulted in actual construction. What this means is that for the nuclear power plants currently in operation in Japan the decision to proceed with construction was made before people knew what nuclear power really was.

The fact is that of all the new NPP plans that have surfaced since nuclear power started operating in Japan and people became aware of the risks involved, not a single one has been built. Higashidoori-1 is the first reactor to commence operations at a new NPP in 12 years, but it took 40 years from the time Higashidoori town council agreed to host an NPP in May 1965.

It should be noted though, that at sites where a nuclear reactor is already operating, resistance to another one being constructed is weak. The subsidy that the government provides for the construction of one nuclear reactor is approximately 20 billion yen. Once it commences operations, the amount of the subsidy becomes minimal and property tax revenue too gradually falls over the years. Even local small and medium enterprises that benefit from peripheral projects associated with the construction of nuclear facilities (only large enterprises can undertake the actual construction) face a sudden fall in revenue once the reactor becomes operational. It is no wonder that some local people wish for the construction of new reactors. There are also people who feel a sense of resignation and say, “Well, there is already one, so what difference does another one make to the danger?”

This is the “secret” as to why so many nuclear power plants have been constructed in Japan. Other reasons include the submissive attitudes towards national decisions, which is more deep-seated in sparsely settled parts of the country. The end result is that there are now 54 nuclear reactors in Japan.

On the other hand, the attitudes of local residents, who in the past were tolerant towards nuclear power, have changed due to repeated exposures of fraudulence by electric power companies and a series of accidents, such as the disastrous nuclear accident at the JCO uranium conversion facility in Tokai Village, Ibaraki Prefecture in September 1999 that resulted in two deaths and neutron radiation exposure to residents in the vicinity of the site, and the pipe rupture at the Mihama-3reactor in Mihama Town, Fukui Prefecture that killed five people and injured six other people in August 2004.

Provincial governments and municipalities that have long followed national policies are gradually changing their attitudes. Fukushima Prefecture, which has 10 reactors with a total capacity of 9,096 MW, has declared that it will aim for regional development without dependence on nuclear-related funds. It assumes that by 2030 all its reactors will have been decommissioned after more than 40 years of operation. Tokyo Electric Power Company’s (TEPCO) position is that its reactors will continue operating for 60 years, hence no reactors will be decommissioned until 2030, but this is unrealistic.

The climate surrounding electric utility business has changed. The partial deregulation of electricity retailing, which began in March 2000, has expanded the scope of liberalization. Total electricity demand has stopped growing. Changes such as these have caused electric power companies to lose interest in constructing new reactors. The new climate even affects the construction of reactors for which construction plans have already been announced. Each year for several years now their construction has been further delayed.

As for the Higashidoori nuclear power plant construction plan, it was originally a large-scale plan envisaging the construction of reactors for TEPCO and Tohoku Electric, with a total capacity of 10GW each. At present, however, plans remain to construct Tohoku Electric’s Higashidoori-2 (ABWR; 1,385 MW) and TEPCO’s Higashidoori-1 and Higashidoori-2 (ABWR; 1,385 MW each), though these plans have been postponed and there is a persistent rumor that they will be cancelled. Even the electricity generated by Tohoku’s Higashidoori-1, which has just began operation, is not accompanied by a sufficient increase in demand. Hence it can only be operated if TEPCO accepts the large excess. Effectively it is a joint reactor. On the other hand, these two companies are now direct competitors in the liberalized electric utility business. Operating simultaneously as partners and competitors, it seems that they have a rocky road ahead of them.

Baku Nishio (CNIC Co-Director)