A business analysis of Japan’s NPP export to Turkey Nuke Info Tokyo No. 161

Leader of a plant engineers’ group monitoring

the decommissioning process of nuclear power plants

|

| Anti-nuclear movement in Turkey, Photo by AntiNükleer Sinop |

Introduction

The Japan-Turkey Agreement for Cooperation in the Use of Nuclear Energy for Peaceful Purposes (hereafter “Nuclear Energy Agreement”) was endorsed by the Japanese Diet on April 18, 2014 and came into effect on June 29, 2014. This agreement paves the way for and facilitates Japan’s export of a nuclear power plant (NPP) to Turkey, along with the agreement on the outline of the NPP export project, the Host Government Agreement (HGA)1 signed by the Turkish government and a Japanese-French consortium earlier, on October 29, 2013.

This project is part of Japan’s public-private sector partnership scheme, jointly devised by the Japanese government, that intends to use infrastructure exports as a spark for expanding the Japanese economy and the nuclear power industry, which has been struggling to find a brighter outlook on the domestic market since the March 2011 nuclear accident in Fukushima. This project is currently being promoted by the government, together with the NPP export project to Vietnam.

Under the current circumstances, where the clean-up operations of the nuclear accident in Fukushima have yet to be completed, large numbers of citizens and intellectuals are expressing various criticisms of the NPP export projects, mainly from technical and ethical points of view. In this article, however, the writer will attempt to explore the problems of NPP exports from a business viewpoint.

Outline of the project

The outline and background to the project will be explained here briefly before getting into the main topic.

NPP operation body: A joint venture financed by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. (MHI), Itochu Corp., GDF Suez S.A., and EUAS (Turkish Electric Power Co.)

Planned construction site: Sinop City on the Black Sea coast

Rated Output: 1,100 MW × 4 units

Type of nuclear reactor: ATMEA1 (advanced reactor jointly developed by the French Areva S.A. and MHI)

Schedule: Commencement of construction in 2017; to begin operations in 2023

Project Cost: US$22 billion – 25 billion

The background to this project is described in Table 1. The Turkish Akkuyu NPP project was launched by a Russian enterprise in 2010, at Akkuyu on the Mediterranean Sea coast. The Sinop project largely follows the pattern of the Akkuyu project.

| 1980’s | The Turkish government examined the feasibility of constructing NPP in the country. |

| May 2010 | The Turkish government placed an order with a Russian company to build the Akkuyu NPP that would be equipped with four PWR units with a rated output of 1,200 MW each |

| From 2010 through 2013 | Negotiations on the Sinop NPP continued between the Turkish government and the governments and businesses of Japan, France, South Korea, China and Canada. |

| May 2013 | Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited Turkey and signed the Nuclear Energy Agreement with his Turkish counterpart. At the same time, the Japanese consortium won the preferential negotiating rights. |

| October 2013 | The Turkish government and the Japanese-French consortium agreed on the construction of the NPP. |

| April 2014 | The Japanese Diet ratified the Nuclear Energy Agreement. |

| Table 1. Background to the plan for the Sinop Nuclear Station in Turkey | |

NPP export business based on official credit

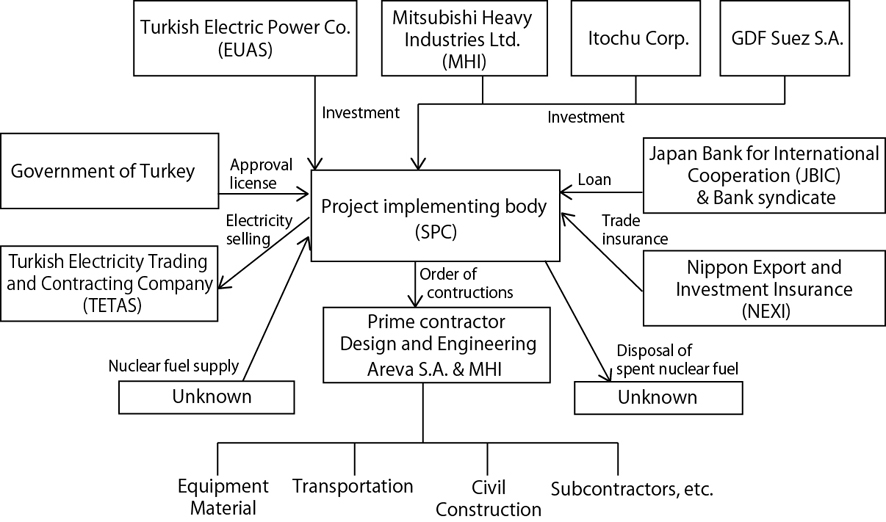

The most important distinguishing feature of this Japanese project is that the NPP “operating business” will be exported. As in the contract with Russia’s state-owned company Rosatom, the contract for this project will be of the BOO, Build-Own-Operate, type. As Figure 1 shows, the special purpose company (SPC) formed by the Japanese-French consortium and EUAS is the implementing body for this project, and will build, own, and operate the facilities.

This means that the project implementing body, consisting of Japanese businesses, financially supported by the Japanese government through the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI), will take on all kinds of risks involved with the project, including commercial, country, operation, accident, environment, nuclear proliferation, and force majeure (Act of God) risks.

Previous NPP exports from Japan were confined to exports of individual equipment items, and for this reason there were limitations on the manufacturer’s liability. The exporters were therefore absolved from consequential responsibility, such as those for negative effects on the plant’s business operations and compensation for third parties. (In the case of the U.S. San Onofre NPP, MHI has been charged with equipment design flaws and is said to be partially responsible for the shutdown of the NPP. The Japanese firm is currently involved in a lawsuit for compensation liability, the amount of which is limited.)

Japanese plant makers, such as MHI, Toshiba Corp. and Hitachi Ltd. have never concluded even a “Lump Sum Turn Key (LSTK) Contract” for exporting facilities and equipment for a complete plant. In the case of the NPP export to Turkey, these companies will be forced to take on enormous and extensive business risks, incomparably greater than those in previous cases of NPP equipment exports.

The biggest problem with the Turkish project is that no scheme has yet been formulated regarding who will pay how much compensation for damage if a severe accident similar to the one at Fukushima occurs. Plans for sharing the costs of accident clean-up operations have also yet to be worked out.

Although it is natural for the project implementing body to take primary responsibility, it would be impossible for the joint venture to pay the full amount of compensation and clean-up costs on its own, as can be seen from the case of Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO) in the Fukushima nuclear accident case. NEXI insurance covers merely the damage involving investment and loans, and it is not permitted to use the insurance money for damage compensation.

Should such an accident occur, will the Japanese government refuse to extend financial support to the Turkish government and force the Turkish counterpart to take full responsibility? Or will the Japanese government shoulder a “suitable portion” of the financial responsibility? In this case, the government will use Japanese taxpayers’ money, but how is it assessing such a risk? The public in the two countries has not been informed of these risks at all.

Even if a severe accident does not occur, there is still the danger of business failure by the NPP for other reasons. JBIC will be burdened with huge unrecoverable loans, or NEXI will have to pay out insurance money.

In either case, the Japanese government will use both tax payers’ money and national bonds to raise the funds, which means a massive outflow of Japanese public assets. JBIC’s existing guidelines do not have provisions concerning the extension of loans for nuclear-related projects involving nuclear proliferation, nuclear accident response, or the disposal of nuclear waste. There is a chance, therefore, that the government will extend official loans to the Turkish NPP project without prudent study. On the other hand, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) bans member countries from offering official development aid (ODA) for NPP projects due to the specificity of the NPP business. Likewise, the World Bank and the Asian Bank refrain from extending loans to the NPP business.

The German government also decided on June 12, 2014 to forbid official credit accommodation to exports of nuclear-related facilities, equipment, and so on. Given this situation, we wonder if JBIC has carried out a facile relaxation of the terms and conditions for extending credit to the Turkish NPP project by taking advantage of the partnership between the public and private sectors in the current environment, where Japan is being forced to compete with Russia, China and South Korea.

As a public financial institution, JBIC is required to take measures to increase transparency of its responsibilities in NPP projects; for example, by devising stricter guidelines on NPP exports, conducting a risk assessment for each project, and evaluating the projects’ anti-disaster measures, such as payment of damage compensation and evacuation of local residents. Other measures that should be taken by JBIC include an assessment of the environment around the plant, evaluation of the national consensus on the project within the importing country, and disclosure of these assessments.

|

| Figure 1. Provisional organizational chart for the export of a nuclear power station to Turkey |

International environment of the NPP business

Affected by the recent international economic environment and the nuclear accidents at the Chernobyl nuclear power station in Russia and the Fukushima nuclear power station in Japan, construction of NPPs is slowing in Japan, the U.S. and Europe, while the planning and construction of such plants are increasing in East Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and Africa. Russian, Chinese and South Korean plant manufacturers are actively engaged in exporting their plants to these countries and regions.

The U.S. nuclear power industry, in particular, is hard hit by the ‘shale gas revolution’ in the country, and is currently suffering from a shrinking domestic market and the subsequent sluggish business. In view of this situation, their major concern now seems not to be profits from their business, but containment of expanding NPP exports from China and Russia to third countries, and prevention of nuclear proliferation. For this reason, they are pinning their hopes on Japan’s funding ability and the powerful alignment of Japanese, U.S., and European plant manufacturers (Toshiba-Westinghouse Electric Company, Hitachi-GE, and MHI-Areva) in winning orders in the international arena.

In other words, the U.S. manufacturers’ intent to prevent nuclear arms proliferation (or a continuation of the monopoly over nuclear arms by nuclear powers) by using Japanese businesses, seems to have matched with the intent of the Japanese public and private sectors to use NPP exports as the main step to prolonging the life of the domestic nuclear power industry.

Significance of NPP business for the exporting companies

When the export of NPPs is looked at from a business viewpoint, exporting companies receive an order worth 1-2 trillion yen on average only once in several years. They are unable to gain the continuous and stable profits they receive from other infrastructure businesses (thermal power plants, water supply and traffic systems) or energy development projects (LNG facilities, etc.). According to Cabinet Office statistics for 2013, orders for infrastructure-related system projects received by Japanese exporting companies totaled roughly 9.3 trillion yen. Although the government’s “Strategy for Infrastructure-related System Exports” says Japan aims to receive annual orders worth around 30 trillion yen in total in or before fiscal 2020, it is unlikely that unstable and unpredictable NPP exports will contribute to the achievement of this target level. As things stand now, it is hard to believe that the NPP exporting business could become the driving force for Japan’s economic growth. For plant exporters, the NPP business that forces them to maintain a large team of plant designers and construction engineers within their corporate organizations, is not a lucrative business.

Rather than for business reasons, there may be other reasons for the continuation of the NPP business. It may be that the companies are forced to continue by both the U.S. administration, striving to prevent nuclear proliferation, and Japan’s so-called “nuclear village,” comprising people in the government, academia and the power industry, who are eager to defend their vested interests.

Moreover, there is a limit to Japanese NPP exporters’ efforts to enhance their competitive power. Although the public-private partnership project to export NPPs has been given special privileges, such as government subsidies for feasibility studies, low-interest loans from JBIC, and NEXI trade insurance, which may bolster their competitive power to some extent, their Chinese and Russian counterparts are far more competitive. These two countries are said sometimes to bundle NPP exports with weapons supplies. For Japanese exporters, the options available for increasing profits are limited. One would be longer-term and sustained value added to projects by supplying nuclear fuel, plant operation guidance, and offering maintenance services for facilities and equipment. Another possible option is to participate in the NPP supply business itself, which would expose companies to the risk of massive losses while providing opportunities to gain considerable profits.

Taking these factors into consideration, Japan chose the option of participating in the Turkish NPP operation business, rather than simply concluding a contract for delivery of plant facilities and equipment. However, each participating country has different reasons for joining the project. Turkey is banking on 1) construction funds being provided by Japan and France, 2) GDF Suez’s experience in plant operation and maintenance, 3) introduction of the state-of-the-art nuclear generation technology (ATMEA1), and 4) the purchase of low-priced electric power (at almost the same price as that of the Akkuyu plant, 12.35 ¢/kWh.). The Japanese government aims to contribute to the U.S. strategy of controlling nuclear proliferation, to extend its record of NPP exports, and to strengthen diplomatic ties with Turkey. Japan’s MHI is counting on profits from the construction of the NPP and from the plant operation, and the addition of the ATMEA1 construction to its company record.

However, this Turkish project, based on different intentions and purposes by the various participants, was launched in disregard of a large number of relevant risks and without forming a consensus within the Turkish and Japanese public spheres. It is, therefore, difficult to predict how long cooperation among the project participants, with their different purposes and intentions, will last.

Spent nuclear fuel and its reprocessing

There is another problem with the Turkish project. This involves the reprocessing and future of the spent nuclear fuel. The Nuclear Energy Agreement2 stipulates in the third clause of Article 2 that the technology and facilities for uranium enrichment, reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel, and plutonium conversion can be transferred from Japan to Turkey only when the agreement is revised to enable such a transfer. In addition, Article 8 of the agreement states that uranium enrichment or reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel can be performed within the territory of Turkey only when the two governments sign a written agreement to that effect.

This means that the transfer of the technology and facilities for uranium enrichment and the reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel are not permitted under the existing agreement, but these might become possible in the future. Meanwhile, the Nuclear Energy Agreement3 with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), ratified by the Diet on the same day, clearly stipulates that the above-mentioned technology and facilities will never be transferred from Japan. This agreement does not include any clause similar to Article 8 of the Nuclear Energy Agreement with Turkey. Why is it that Japan provides the opportunity for the transfer of such technology and facilities only to Turkey? When we take into account Turkey’s geopolitical position, we may become apprehensive over the country’s future move toward domestic production of plutonium, and nuclear proliferation.

Furthermore, the nuclear energy agreement with Turkey has no clause on disposal or return of the spent nuclear fuel. The Japanese nuclear fuel cycle has collapsed and the plans for final disposal of nuclear waste have run into intractable problems. The consequence of this is that the amount of spent nuclear fuel stored in Japan has snowballed to an uncontrollable level. The Japanese government thus has the responsibility, as an implementing body of the Turkish project and provider of official loans and trade insurance, to explain clearly about spent nuclear fuel disposal to the public in both Turkey and Japan. In any case, it is unthinkable for the participating countries to carry this project forward without resolving the problem of where the spent nuclear fuel will end up.

Concluding remarks

Indications are that the NPP export to Turkey will force the accident risks on the Turkish public and the greater part of the financial risk on the Japanese public. Moreover, the public-private sector partnership promoting the project will potentially contribute to further expansion of the bloated vested interests of the so-called “nuclear village,” and strengthen the cozy relations between the two sectors on a global scale. This will hamper the healthy competition that exists among businesses under normal conditions, and erodes corporate governance. One of the major causes of the Fukushima nuclear accident and expansion of the disaster was the dysfunction of the TEPCO corporate organization. Taking this into consideration, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that NPP projects that can only proceed if they are based on public-private partnership, such as the proposed Sinop NPP export project, lack the basic qualifications for sound business. Our perception should be that the Fukushima nuclear accident has provided us with an opportunity to review Japan’s nuclear power policy from various viewpoints, including that of business, and it is our international responsibility to inform the global community of this perception.

1). MHI press release October 30, 2013

www.mhi.co.jp/news/story/1310305438.html

2). Nuclear Energy Agreement with Turkey

www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/000018110.pdf

3). Nuclear Energy Agreement with UAE

www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/000004075.pdf