Review of the Japan Atomic Energy Commission Nuke Info Tokyo No. 152

|

|

Government’s reorganization of JAEC carried out in 2001 forced them to work together with the officials of private-sector companies

|

The Innovative Strategy for Energy and the Environment announced in September 2012 called for a fundamental review of the Japan Atomic Energy Commission (JAEC). It stipulates that the nuclear power policy would henceforth be decided primarily by the Energy and Environment Council, comprised of the Cabinet members concerned. It also said the government would carry out a fundamental review of the commission by setting up a panel to discuss the feasibilities of dissolving or streamlining JAEC, taking into consideration its functions, one of which is to verify the use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes.

Even after the law on the Nuclear Regulation Authority was enacted on June 20, 2012, no changes were made to the laws and regulations related to JAEC, and its tasks were also basically left unchanged. Now the government is set to change this situation and discuss the feasibility of dissolving or streamlining the commission. The reason why it has decided to do so is because it has gained a perception that some of the tasks stipulated by the law have lost substance and become dead letters.

The feasibility of dissolving JAEC was included in the Innovative Strategy amid the situation where the revision of the New Framework for Nuclear Energy Policy was being deliberated by JAEC’s Council for a New Framework for Nuclear Energy Policy. The primary factor behind this move seems to have been the media’s revelation of secret meetings held for nuclear power suppliers by JAEC. The Mainichi Shimbun disclosed the existence of the secret meetings in its May 24, 2012 issue and has since repeatedly reported on them.

According to the reports, JAEC discussed the direction of the deliberations by its Council for a New Framework for Nuclear Energy Policy and its technical subcommittee on nuclear power and nuclear fuel cycle with the electric power utilities at the secret meetings, and consulted with them on how to respond to the opinions presented by members of the Council and subcommittee. The disclosure severely damaged public confidence in JEAC.

As a result, the deliberations by the Council for a New Framework for Nuclear Energy Policy, suspended with the outbreak of the nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, were halted once again. The council itself was eventually abolished in accordance with the Innovative Strategy.

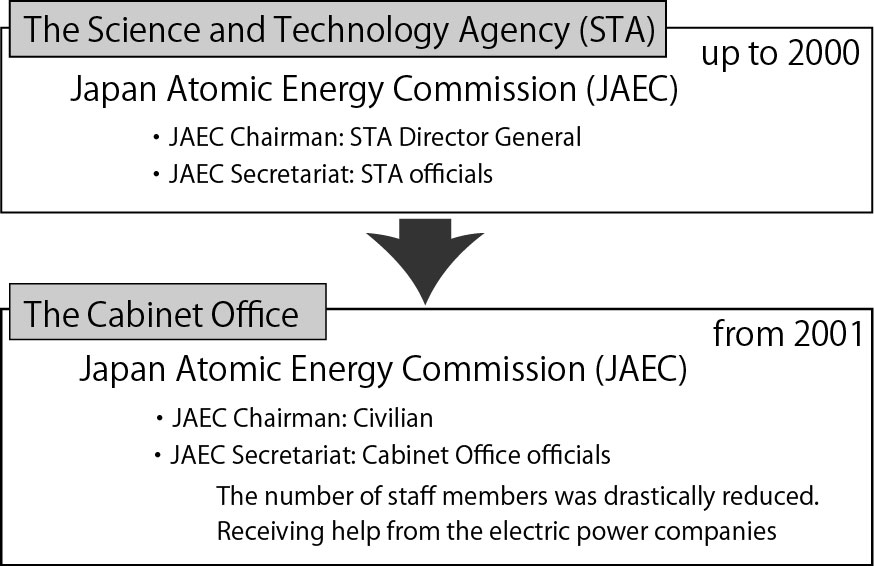

Why were the electric power suppliers participating in the meetings of JAEC’s clerical staff? This practice means that JAEC had cozy ties with the electric power utilities. But JAEC gave the excuse that the government’s reorganization of its commission carried out in 2001 forced them to work together with the officials of private-sector companies.

JAEC was established as internal subdivisions under the Science and Technology Agency (STA), and the agency officials were in charge of JAEC’s clerical work. At that time, The STA Director General also filled the post of the commission’s chairman.

However, STA was disbanded in the organizational realignment and JAEC was placed under the Cabinet Office. A new system of appointing a civilian as chairman of the commission was introduced, and the officials of the Cabinet Office were charged with carrying out JAEC’s clerical work, but the number of staff members was drastically reduced.

Since then, JAEC routinely accepted help from private-sector enterprises. JAEC Chairman Shunsuke Kondo said the commission began receiving help from the electric power companies when its office was moved to the Cabinet Office (However, Kondo was not the JAEC Chairman at that time.) Kondo appeared to have been fully aware that the acceptance of such help from power suppliers would undermine the neutrality of the commission. Kondo thus created an excuse that the utility officials came to the JAEC office to attend meetings of his private consulting group.

The National Policy Unit has investigated the secret meetings and has concluded that the deliberations by the Council and the subcommittee were affected and swayed by the secret meetings. Taking this conclusion into consideration, the government included the above-mentioned measures against JAEC in the Innovative Strategy.

In response to this, a panel comprised of intellectuals for reviewing JAEC was set up within the National Policy Unit, which was headed by then National Policy Minister Seiji Maehara. The ten intellectuals on the panel began deliberations on this issue on October 19, and this writer participated in the deliberations as one of the members.

This was at a time when the general election was likely to be held soon (it was actually was held on Dec. 16), and a change of government was anticipated. The members therefore compiled a report entitled “Basic Policy for Reviewing JAEC” based on the results of a total of six meetings, and submitted it to Mr. Maehara on December 18. This was a kind of interim report, rather than being a final report.

The law for establishment of the Japan Atomic Energy Commission stipulates that the commission is tasked with:

1) work concerning the policies on the use of nuclear energy,

2) coordination and adjustment of clerical work among the related administrative offices,

3) work to estimate and allocate costs,

4) work to check the financial basis of applicants for licenses and authorization, and work to ensure licensees’ peaceful use of nuclear energy,

5) work concerning financial assistance for research and experiments,

6) work concerning the education and training of researchers and engineers (except for those provided by colleges and universities),

7) collection of related information and data, and formulation of statistics, and

8) other matters of significance.

The tasks to be carried out by JAEC or its successor organization were decided upon as follows.

All the members of the panel shared a perception that 4) work to ensure peaceful use of nuclear energy by the applicants for licenses or authorization is a very important function that should be left in the hands of JAEC or its successor organization. This writer insisted in the panel meeting that there is a need to not only forestall all actions that could lead to development of nuclear weapons, but also to implement the nuclear-waste recycling (uranium enrichment) policy and other related policies with strong authority, in order to ensure the strictly peaceful use of nuclear energy.

In connection with the enactment of the law for establishing the Nuclear Regulation Authority(NRA), the Atomic Energy Basic Law was revised, and will be put into effect in July 2013. With this revision, a phrase, “to contribute to national security of this country” was included in the basic policy for the use of nuclear power. It is needless to say that this revision has raised concerns among other countries that Japan may begin to arm itself with nuclear weapons.

The government has explained that the phrase means “to contribute to protection of nuclear materials and facilities,” and for this reason there is no need to allow any extraneous interpretation of the phrase to take root in society.

However, it is difficult to dispel this concern when we consider two factors; the fact that the phrase was proposed by hawks in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party as an amendment to the law, and the circumstances whereby a new government led by the hawkish Shinzo Abe has been established.

The panel’s consensus is that 1) work concerning nuclear energy policies can be eliminated from the list of JAEC or its successor organization’s tasks. Admittedly the policies on nuclear power generation have already been managed by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), along with the policies on other types of power generation. As to the direction of the nuclear power policy, a system is already in place in which METI’s advisory committee (Nuclear Energy Subcommittee) deliberates on the issue and the results of its deliberations are reflected in the Basic Energy Plan.

5) work concerning res earch and development is currently managed by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). Since JAEC’s authority does not extend to the two ministries, the commission has no option but to formulate its policy (framework) by combining the policies of the two ministries.

The Basic Energy Plan is presented to the Diet, but the lawmakers do not deliberate on it, so I proposed to the panel meeting that the Basic Energy Plan be deliberated in the Diet.

With regard to 3) allocation of costs, JAEC is currently engaged in the collection of budgetary requests from relevant ministries and agencies, but it has already lost the function of allocating budget. JAEC announces its policy when it submits its budgetary request but the policy is merely a combination of the policies from the ministries and agencies involved.

Task 4) will be transferred to the Nuclear Regulation Authority from April 2013. The task is to manage nuclear materials, including confirming the data provided by the applicant for a license or authorization and inspecting their facilities (This work is currently carried out by MEXT.).

With regard to the task of ensuring the peaceful use of nuclear energy when granting approvals and licenses (one of the conditions for granting approvals and licenses stipulated in Article 24 of the Nuclear Reactor Regulation Law), thus far MEXT has examined each approval or license, which is then rechecked by JAEC.

However, the reality was that JAEC checks were sloppy. Because the commission conducted the checks under the assumption that the nuclear power supplier’s guarantee of the peaceful use of nuclear materials was reliable and trustworthy.

JAEC had previously decided on the policy that Japan will not possess surplus plutonium in order to enhance transparency in the use of the nuclear material, and ordered the suppliers to submit their plans on the utilization of plutonium before they began separating the material from spent nuclear fuel. Although this check was a mere formality and the JAEC approved such plans whenever it received them, this system seems to have worked to some extent as a kind of role to ensure the peaceful use of nuclear materials.

The panel was unable to decide on whether JAEC or its successor organization should do the clerical work for ensuring the peaceful use of nuclear energy, or whether they should be charged with the work on other major policies, because this decision should be made with reference the future structure of the organization.

Task 5) was also transferred to another council, the Council for Science and Technology Policy. Task 6) is currently carried out by MEXT. Concerning task 7), many members of the panel said it is convenient and helpful if one organization collects various kinds of information from the ministries and agencies concerned.

The panel was unable to discuss in detail the issue of how JAEC should be reorganized or abolished. One member said the panel should not decide on this issue without holding thorough discussions.

Although the JAEC exerted great influence in the early stages of nuclear development, Japan has already passed through the stable period and entered the declining phase. It is not too much to say that JAEC has completed its basic role. When the Science and Technology Agency was disbanded, JAEC remained intact. But the occurrence of the nuclear crisis in Fukushima and the formulation of the Innovative Strategy triggered the debate on the commission. Considering these overarching changes, the question is how to scale down or abolish JAEC by selecting the functions that should be left in its hands.

Although this is the general direction of the flow of the tide, it is difficult to presume that the Abe government will maintain this policy as it is. How seriously and how deeply the new government will tackle the JAEC issue may become clear by sometime around July.

(Hideyuki BAN, Co-director of CNIC)