Who’s Who: Yoshizawa Masami and the Ranch of Hope

(Interviewed by Caitlin Stronell, NIT editor)

Following the meltdowns at TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station in March 2011, the government issued an order that all livestock within a 20 km radius of the plant be slaughtered because radioactive contamination had made them unfit for human consumption. Even before this, large numbers of livestock and pets had died of starvation because their owners had been ordered to evacuate and could not enter their homes and farms to take care of the animals. Yoshizawa Masami was managing a farm in Namie Town, where he lived with his 330 beef cows. Even though the farm was within the 20 km No Go Zone, he refused to leave his cows to death by starvation and continued to live at the farm, having to sometimes break through barricades erected to keep people out of the radioactive area, so he could get feed for them. Not only was he risking his own life and health by living in the contaminated area, he had also lost his income because he would never be able to sell the cows he was raising as beef.

Yoshizawa-san thought long and hard about this and says he is still wondering if what he is doing has any meaning. “I’m a farmer. I raise cattle so that I can sell them as beef. And because of the nuclear disaster the cows can never become beef, but …is that their only value? The cows are also a life.”

In the aftermath of the Fukushima Daiichi meltdowns, the way that living creatures were being treated disturbed Yoshizawa-san. He claims that 1,500 cows died of starvation and he saw so many carcasses of emaciated livestock and pets that he felt this must be what Hell is like. There was so much death and destruction caused by the nuclear disaster and when the government, one of the main proponents of nuclear power, instead of taking responsibility for its mistaken policy and trying to protect lives and livelihoods, gave the order to slaughter all livestock, he felt this was completely wrong and he refused to kill his cows.

His resistance has continued for nearly 11 years. His cows are symbols of this resistance, by simply being alive. They remind us of the anguish that other farmers felt as they had to let their animals die or slaughter them because radioactive contamination had made them ‘worthless.’ Despite the deep wounds that this caused to many Fukushima farmers and residents, Yoshizawa-san named his farm the ‘Ranch of Hope.’ His hope is that by the time his last cow dies a natural death, Japan will be nuclear-free. But there is a deeper meaning of ‘hope.’ These cows show that human beings are capable of protecting lives instead of abandoning or destroying them, even in desperate situations. There is hope that our better nature will prevail.

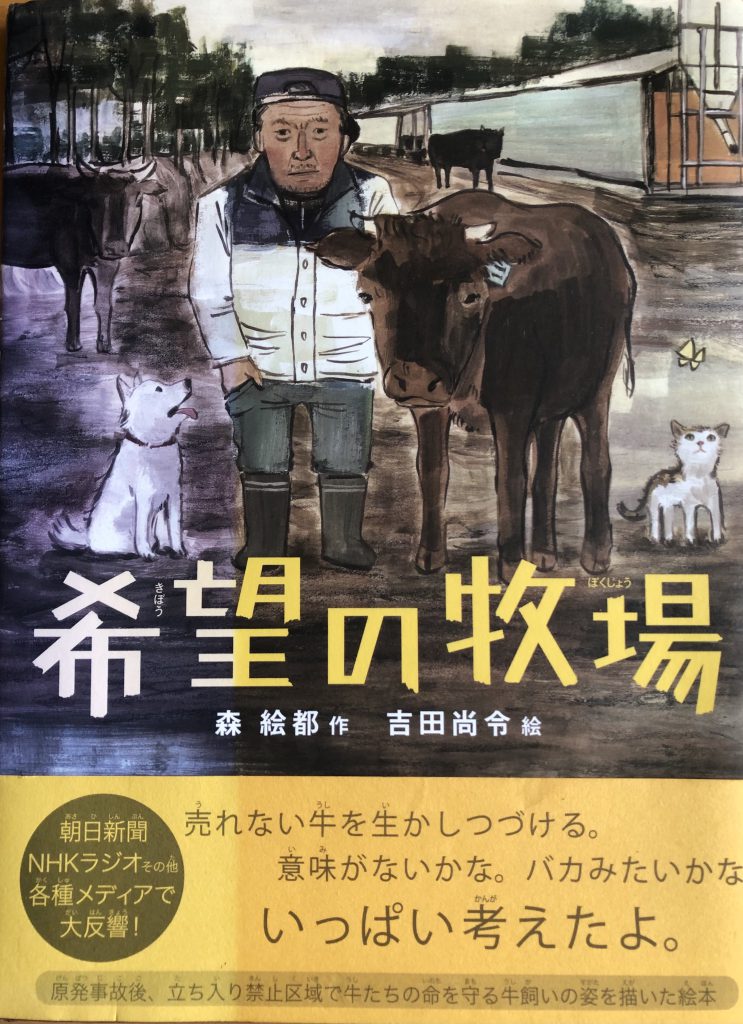

But in order for this hope to be realized, Yoshizawa-san insists, people must speak up. We must raise our voices when we feel something is wrong. We must take action. Yoshizawa-san’s actions are varied and creative. His ‘Godzilla cow truck’ blaring the Godzilla theme music punctuated by the occasional ‘moo’ is a common sight at any anti-nuke protest in Tokyo. In 2014 a beautiful picture book was published telling the story of his cows and the nuclear disaster. He travels around Japan speaking at schools, and can see by the reactions of the children and the look in their eyes that they understand the sanctity of life much better than many adults. But he encourages them to act on this. To speak out and to try to change things that are wrong. “At one of the junior high schools where I’ve been speaking every year for six years, one of the teachers told me that they are having an election for the student council. They never had one before, mostly the student council was hand-picked by the teachers, but this time, apparently there are four candidates!” Yoshizawa-san tells me. I think this is exactly what he means by ‘hope’ and I could understand how he and his cows could inspire this feeling, which, as activists, is perhaps what we all need most.