Nuclear fusion is a never-ending dream

By Nishio Baku (CNIC Co-Director)

The Green Transformation (GX) Basic Policy proposed by the Japanese government mentions nuclear fusion as one of the next-generation innovative nuclear technologies in its reference information. I doubted my ears when I learned that the Nuclear Energy Subcommittee of the ministerial Advisory Committee for Natural Resources and Energy, which drafted the policy, brought up nuclear fusion as one of the “innovative technologies” to be pursued. It was a big surprise. That is the very nuclear fusion that, at the Second International Conference for the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy of September 1 through 13, 1958 in Geneva, Dr. H. J. Bhabha from India, who chaired the conference, flamboyantly predicted would take shape in 20 years. It has been 64 years since then. The government refers to this vintage technology as “innovative”.

During the decade of the 1980s, various Japanese universities received more budget than previously from the government for nuclear fusion research. The website of professor Takabe Hideaki, Institute of Laser Fusion, Osaka University, notes on September 10, 2014 that, during the days of the Second Oil Crisis, when Gekko XII [the experimental laser fusion apparatus at Osaka University] was completed, the government’s top-down initiative provided the university with a budget of 30 billion yen (in the value of the yen at the time), to build the laser system and a robust building for it. I find this maybe a special case (another document I have with me says, of the fiscal 1984 national budget, 35 billion yen was given to the then Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corporation and a total of 7 billion yen to universities). Uramoto Joshin, a former associate professor at the National Institute for Fusion Science, wrote in his retirement memoir “My Final Words as a NIFS Staff” (NIFS News, May 1998), that he was in a festive mood around the time when he joined the former Plasma Research Institute of Nagoya University, which was one of the founding bodies of the NIFS. The boom faded, and in 1989, the Plasma Research Institute was reorganized as the National Institute for Fusion Science, an inter-university research institute, into which a part of the Heliotron Plasma Physics Laboratory at Kyoto University and a part of the Institute for Fusion Theory at Hiroshima University were incorporated. The technology that the government refers to is the same nuclear fusion.

In what respect can the nuclear fusion reactor be a “next-generation innovative reactor”? While there is no full-size nuclear fusion reactor, what would a “compact nuclear fusion reactor” look like?

Today, “private-sector nuclear fusion” by venture companies seems to be enjoying a global boom. The October 2022 issue of the Journal of the Atomic Energy Society of Japan carried a story about nuclear fusion technologies being developed by private funds in this country. Kyoto Fusioneering Ltd., one of those ventures, confidently declared on July 6, 2022 that for the first time in the world it had completed the basic design of the plant UNITY (“unique integrated testing facility”), which will enable the testing of nuclear fusion power generation, and that the company has started plant construction to commence power generation testing at the end of 2024. “UNITY will realize a high-temperature, high-magnetic-field environment that exactly simulates the nuclear fusion reactor interior without using radioactive material, demonstrating the operation of the integrated power generation equipment.” This plant does not, therefore, perform nuclear fusion power generation. I would not call this meaningless, because developing a nuclear fusion reactor suitable for practical use is said to be one of the big challenges in nuclear fusion technology development; however, to the extent of what I have understood from the promotional video of the company, the project did not seem very practical.

On December 13, 2022, the United States Department of Energy announced that the National Ignition Facility (NIF) of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which researches into and develops atomic weapons, succeeded on December 5 in a nuclear fusion ignition that resulted in an energy gain between before and after the reaction. The NIF is a gigantic nuclear fusion facility that employs inertial confinement fusion using laser radiation, unlike the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), etc., which uses magnetic confinement fusion. The NIF laser system, the world’s largest and most powerful laser system, supplied 2.05 megajoules (MJ) of energy to the target, and gained an output of 3.15 MJ. However, the NIF is not designed to demonstrate practical nuclear fusion energy and consumes around 300 MJ of electric power of each time it executes a 2-MJ laser shot.

Whatever the case, the ignition lasts only one instant.

How far will the muddy road continue?

This nuclear fusion was mentioned by Prime Minister Kishida in his administrative policy speech on January 17, 2022 with the cryptic reasoning that it would help achieve the 2050 goal of carbon neutrality. Using this as the basis, the government set up the Nuclear Fusion Strategy Expert Panel under the Integrated Innovation Strategy Promotion Council of the Cabinet Office. The panel had its first meeting on September 30, where Takaichi Sanae, Minister of State for Science and Technology Policy, said: “I have a strong will to accelerate the efforts to commercialize nuclear fusion technology as far as possible.” However, the Innovative Reactor Working Group placed under the Nuclear Energy Subcommittee, states in its “Roadmap for Introduction” (August 9, 2022) that whether the construction of a prototype nuclear fusion reactor should start or not will be determined in the mid-2030s. What would “commercializing nuclear fusion” mean at this point?

I wonder how much longer this fusion boom will continue. “As I am leaving this institute, I breathe a sigh,” Associate Professor Uramoto said in his NIFS retirement memoir. “The development of the toroidal [magnetic confinement] nuclear fusion reactor is totally blocked by three challenges: One, abysmally high cost (trillions of yen more in the future?) and a mind-boggling long time (more than 50 years); two, gigantic and complicated systems (a mega-sized system cannot be handled unless simple); and three, the heat-resistant material and radiation-proof material for the reactor walls are not available on earth.”

For the cost, the Special Committee on the ITER Project of the Japan Atomic Energy Commission bragged about ITER in its report, “International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) Project Forecast” (May 18, 2001): “It is difficult to correctly estimate the cost required to realize a nuclear fusion reactor, and moreover, it is almost impossible to estimate the size of the benefits obtained from the realization of such a reactor. This committee regards the investment in nuclear fusion energy as an insurance for the freedom of human beings in the future.” “If new energy is unnecessary, nuclear fusion energy would not be put into practical use even if it is technically completed. People would not feel, however, that they invested in vain and made a loss, because the investment was an insurance.”

In 1998, Uramoto said that nuclear fusion power generation would take more than 50 years. Half of that time has already passed. A clever leviathan would have already decided to give up and withdraw.

Of the challenges Uramoto pointed out, the second one, “gigantic and complicated systems (a mega-sized system cannot be handled unless simple)” and the third one, “the heat-resistant material and radiation-proof material for the reactor walls are not available on earth” remain unsolved, despite the passage of so many years.

The pot is calling the kettle black

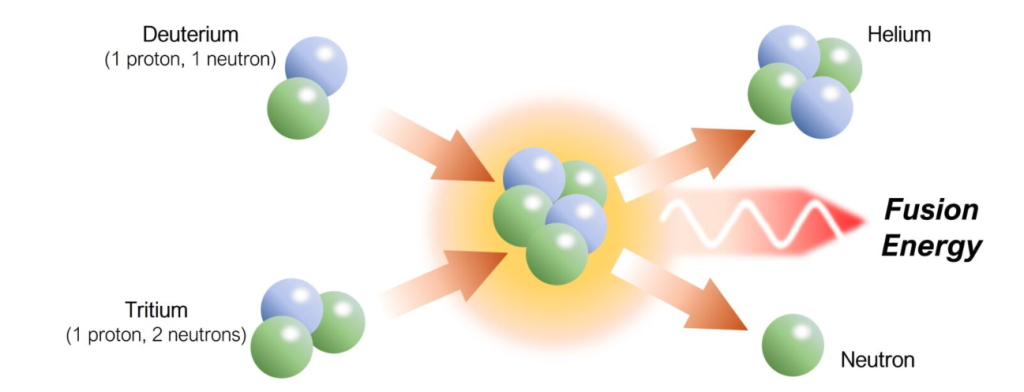

It is meaningless to compare nuclear fusion with nuclear power generation, but some say: “Nuclear fusion is clean.” In terms of the radioactivity released when a large accident occurs, nuclear fusion technology would emit less radioactivity than a conventional nuclear plant. However, the daily releases of radioactive materials from nuclear fusion would be greater than those from a conventional nuclear power plant. Nuclear fusion is also more likely to leak tritium and radioactive gas. It will produce four times as much energy as nuclear fission while producing seven times as many neutrons. Workers in the fusion plant would be exposed to radiation, and people in the neighborhood would also be exposed due to sky shine. Plant equipment would be strongly radiated and easily embrittled, requiring frequent replacement, producing a huge amount of highly contaminated wastes.

Fujiie Yoichi, who was a professor at the Institute of Plasma Physics, Nagoya University, and later chaired the Atomic Energy Commission, said: “If I were asked which would be safer between a nuclear fission power generation plant and a nuclear fusion power generation plant if they were built at the same site under the same conditions, I would not be able to answer. I would only say, ‘I don’t know.’ If I were further asked if it is totally impossible to answer, I would say in a low voice: ‘If it comes to an accident, a nuclear fusion reactor would be easier to cope with, while in normal operation, a nuclear fission reactor would be easier to handle’” (quoted from the proceedings of a symposium entitled “Studies on Nuclear Fusion Reactor Design and Evaluation” held at the institute on August 7, 1980).

The November 1994 issue of Nuclear Engineering, Hiraoka Toru, a special researcher of the then Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute stated: “The nuclear fission reactor was, say, a gift from God, realized quite naturally in a short period of time. On the other hand, the development of a nuclear fusion reactor is a ‘forced’ technology that goes against God’s will, requiring great cost and a very long time to develop.”

Since that time, I have never heard that any gift of God has been discovered.