Kaminoseki Interim Storage Facility Plans Should be Scrapped

Emergence and Outline of the Interim Storage Facility Plans

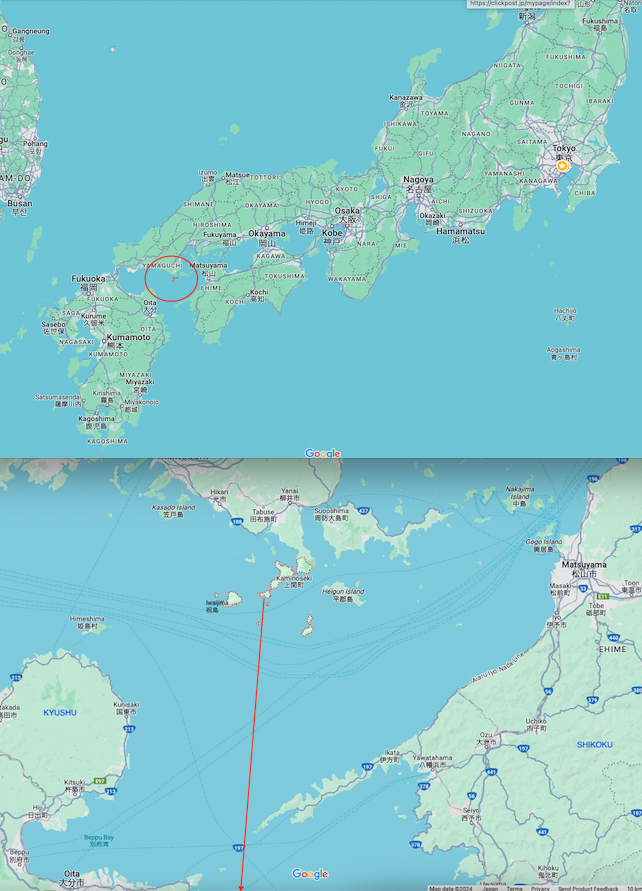

The upper map shows the location of Kaminoseki in the western part of Japan (Yamaguchi Prefecture). The lower map shows more detail of the surroundings and the part of Kaminoseki Town which is being considered for the interim storage facility.

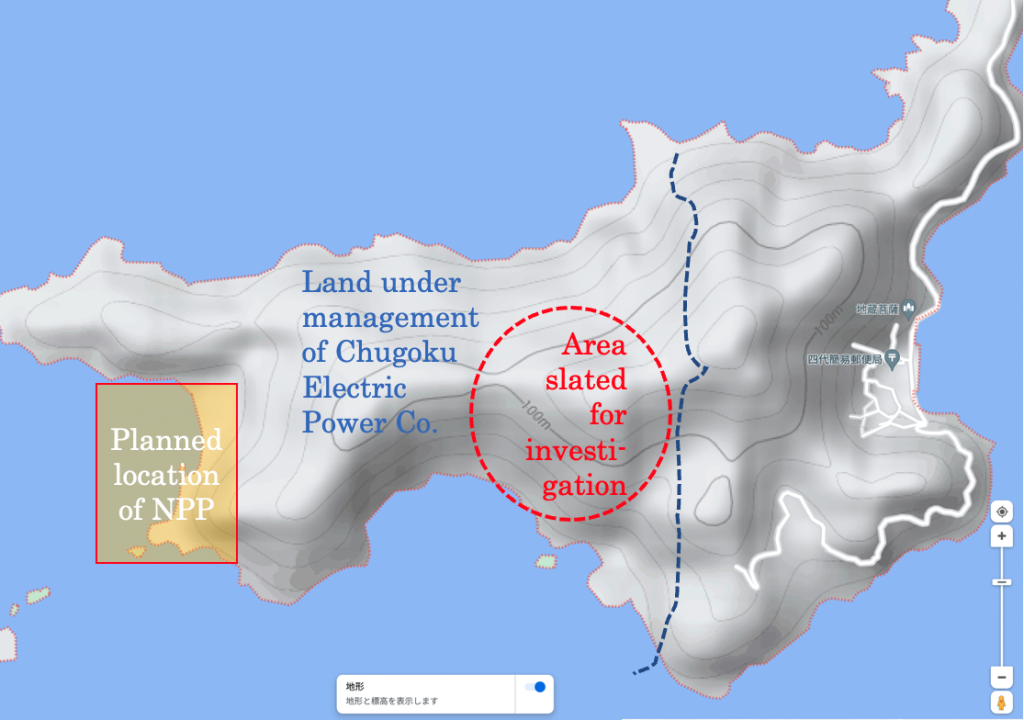

On August 2, 2023, Chugoku Electric Power Co. (Chuden) proposed plans to Kaminoseki Town for interim storage facilities to be constructed on its land holdings where it has also planned to site a nuclear power plant (NPP). The proposal, submitted by Managing Executive Officer Ohseto Satoshi, who was beset by opponents on his way into the town offices, seeks a joint venture with Kansai Electric Power Co. (Kanden) to build a facility with the capacity to store 2000 tons of spent nuclear fuel. It came about as a response to Kaminoseki Town’s request to Chuden for new regional revitalization measures, given that currently its nuclear power subsidies are decreasing.

Kaminoseki Town began receiving subsidies in 1984, starting from a grant for measures to promote the siting of important facilities such as power sources, with a further subsidy added in 1986 for countermeasures to thermal effluents from areas hosting power sources, and another subsidy added in 1996 for measures necessary to promote the siting of important power sources. (These subsidies were unified in 1999 as a result of system changes.) These subsidies were incorporated into the Electric Power Development Master Plan in 2001, and have continued to the present time. Averaging about 200 million yen a year in the 35 years following 1984, these subsidies have decreased during the past seven years and are now about 7.8 million yen a year.

Electric Power Development Master Plan in 2001, and have continued to the present time. Averaging about 200 million yen a year in the 35 years following 1984, these subsidies have decreased during the past seven years and are now about 7.8 million yen a year.

During the 20 years of the former Mayor Kashiwabara Shigemi’s administration, efforts were made to eliminate the town’s dependency on the subsidies, but the situation changed in 2022 with the election of a new mayor, Nishi Tetsuo, who has shown a strong interest in nuclear power. In 2019, the former mayor had town assembly members take a study tour of the interim storage facilities at the Tokai NPP, which are operated by Japan Atomic Power Co. (JAPC), so it could be said that even Kashiwabara seems to have been trying to play to both sides of the nuclear issue.

Mutsu City’s Interim Storage Facilities for Spent Nuclear Fuel

There are differing policy positions for interim storage facilities for spent fuel depending on the purpose they will serve after their completion. Japan has been adhering to a policy of reprocessing all spent fuel, so interim storage means storing it until it can be reprocessed. In the cases of countries that do not reprocess it, it means storing it until its final disposal.

Also, in this case, the storage method uses a dry system. The spent fuel is loaded into combined-use shipping and storage containers and stored that way. In some cases, it is stored on-site at the NPP, and in other cases, off-site. On-site storage is being conducted or planned at the Fukushima Daiichi, Tokai Daini, Hamaoka, Ikata and Genkai NPPs among others (Table 1). For off-site storage, Recyclable-Fuel Storage Co. is building facilities in Mutsu City, Aomori Prefecture. Established jointly by Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO) and JAPC, the plans are for this company to handle spent fuel storage for both companies.

The interim storage facilities in Mutsu City will mainly consist of port facilities, single-purpose access roads and vehicles, and storage buildings. The weight of the objects to be transported will exceed 110 tons. Impenetrable fences have been built around the facilities to protect the nuclear materials, with monitoring equipment keeping watch over them 24 hours a day, 365 days a year to prevent unauthorized access.

The final scale of storage will be 5,000 tons of uranium (tU), with TEPCO accounting for 4,000 tU and JAPC for the remaining 1,000 tU. The facility will consist of two buildings, the first of which (BWR 2,600 tU, PWR 400 tU) has been completed. No spent fuel has been placed there yet, however.

According to the business permit application, submitted to the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency on March 22, 2007, it will depend on the type of nuclear fuel, but in the case of large casks of spent fuel, holding 69 BWR fuel assemblies, the fuel assemblies within them will have been allowed to cool for 18 or more years after their retrieval from the reactor. Medium-sized casks with a capacity of 52 assemblies will take assemblies that have cooled for eight or more years. Meanwhile, for PWR fuel, casks with a capacity of 26 PWR fuel assemblies will take assemblies that have cooled for 15 or more years. There are to be 288 storage containers in all. The dose rates will be limited to 2 mSv/h at the cask surface, or 100 μSv/h at one meter’s distance from it. The construction costs will come to 28.5 billion yen.

Explanations and data provided by Recyclable-Fuel Storage Co. to Mutsu City put construction and other costs for the first building at about 100 billion yen, 70-80 percent of which will be accounted for by the costs of the combined-use shipping and storage containers, and the remaining 20-30 percent, by construction costs for the facilities. Specific details of these figures have not been revealed. Currently, additional construction is underway to meet the new regulatory standards, so we can expect the costs of constructing the facilities to increase.

According to the above-mentioned business permit application, 300 tU per year of spent fuel is to be accepted in the same ratio as above, 260:40. Recyclable-Fuel Storage Co., however, has become less willing to handle medium-sized BWR casks and PWR storage. In September 2023, it reapplied for PWR storage.

A written agreement between Aomori Prefecture, Mutsu City, TEPCO and JAPC (dated October 19, 2005) stated that the storage period is to be 50 years from the starting date of their common use of the buildings. After those 50 years have passed, the stored materials are to be transported to future reprocessing facilities to be built as follow-ups to the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant under a policy of reprocessing all spent nuclear fuel. The new facilities will be necessary because the length of time the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant can operate has been set at 40 years. If no subsequent reprocessing plants are built, there will be no place to send the spent fuel. There is a pressing need to determine how that will be handled—will the spent fuel’s storage be extended into the long term or will it be returned to each of the NPPs of origin? According to the agreement, these discussions must be concluded within 40 years after the storage period begins. A safety agreement is scheduled to be concluded at the stage when details on emplacement of the spent fuel are confirmed. Note that transportation of the spent fuel will begin as soon as the Nuclear Regulation Authority’s prohibition of the transport of fuel to the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa NPP is lifted.

Against the Backdrop of the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Flop

What has thrown the spotlight on dry storage of spent nuclear fuel has been the delays in completing the construction of the Rokkasho Processing Plant. By transporting their spent fuel to this plant, each of Japan’s electric power companies was hoping to avoid shutting down their NPPs when the spent fuel pools belonging to each filled up completely. However, after undertaking an active test run in which it reprocessed 425 tU of spent fuel in 2008, the plant shut down and has remained closed for the 15 years since. Though construction of the plant began in 1993, it has yet to be completed 30 years later. Japan Nuclear Fuel, Ltd. has announced a completion date of early 2024, but in fact, it is having trouble getting its designs and construction work for additional safety measures approved, so completion is expected to face further delays.

The Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) (as the current Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) was called during the 1990s) compiled and published a report recommending that expansion of the storage capacity for spent fuel be ensured by 2010, but none of the electric power companies took that action. In response, METI established a “Spent Fuels Countermeasures Promotion Council,” and asked each of the electric power companies to take measures, thus managing to ensure progress. The Council’s constituents were Japan’s nine electric power companies; the Federation of Electric Power Companies; the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry; the director and deputy director of the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy; and the general manager of METI’s Electricity and Gas Industry Department. To date, the Council has met six times. At first, they focused on reracking spent fuel pools (a measure for increasing storage capacity), and as definite progress has been made in that direction, they have turned their focus toward the above-mentioned dry storage. If they fail to make progress there, they risk being forced to shut down NPPs.

What enabled interim storage facilities to be built in Mutsu City was extremely severe economic conditions faced by the city, but there is also a connection to the decommissioning in 1992 of the nuclear-powered ship “Mutsu.” The ship’s hull was cut at that time and the central section with the nuclear reactor was removed. The ship was then rebuilt as the “Mirai” oceanographic research vessel. Meanwhile, the retrieved nuclear reactor was housed in a pavilion next to the port, where it can be viewed. The port facilities that served the nuclear-powered ship Mutsu have come to be used as port facilities for the interim storage facilities.

Time for Kanden to Make Good on its Promise to Fukui Prefecture

In particular, it is Kanden that is squeezed for storage space. Specifically, storage space at its Takahama NPP will run out in a few years (Table 2).

Kanden would like to adopt dry storage, but this would require shipping the spent fuel out of Fukui Prefecture. In addition, during Kurita Yukio’s four terms as Fukui’s governor from 1987 to 2003, Fukui Prefecture was requesting that spent fuel be shipped out of the prefecture. In 1998, under the condition of having the reracking of spent fuel approved, Kanden promised to select candidate sites outside the prefecture by the year 2000, and in 2015, it made plans to establish a destination for the spent fuel outside the prefecture by 2020 under the condition that Takahama Units 3 and 4 be allowed to restart, with a facility at a scale of 2,000 tU to be operational by around 2030. In addition, in 2017, it indicated a strong intention to present a specific planned site in 2018 under the condition that Ohi Units 3 and 4 be allowed to restart. With no prospects for destination sites, however, it extended the 2018 deadline to 2020, and in 2021, it asked to be allowed to confirm a destination site by the end of 2023, under the condition that Mihama Unit 3 and Takahama Units 1 and 2 be allowed to restart. If that were not possible, it declared, it would have these three reactors halted.

At that time, Kanden also proposed joint use of Mutsu City’s interim storage facilities. This, however, was not based on achievement of even an informal agreement. The Federation of Electric Power Companies and the government pushed for joint use of Mutsu City’s interim storage facilities, but Miyashita Soichiro, then mayor of Mutsu City, rejected this. Miyashita later became governor of Aomori Prefecture in June 2023, and Kanden’s joint use proposal was withdrawn.

Kanden has continued blundering around in search of solutions. In June 2023, the Federation of Electric Power Companies announced a policy of conducting demonstrative research with Orano SA of France on spent MOX fuel reprocessing. The research is to be conducted using 10 tons of Kanden’s MOX fuel. Orano requested 190 tons of spent nuclear fuel needing reprocessing, because from the perspective of managing plutonium criticality, spent MOX fuel needs to be mixed with spent uranium fuel. A complicated system was established, with Kanden contracting with JAEA for the research and the Nuclear Reprocessing Organization of Japan (NuRO) entrusting Orano with the reprocessing. The plutonium recovered through the reprocessing would be made into MOX fuel and returned to Kanden. Given the trends since the Fukushima nuclear accident, this demonstrative research can be said to be basically unnecessary.

Nevertheless, Kanden is proclaiming that it has fulfilled its promise to transport the spent fuel outside Fukui Prefecture. This has met a cold reception, however, at the Fukui Prefectural Assembly, because at a scale of 2000 tons of outshipping, it would be no more than a mere tenth of the response called for.

What emerged next was the proposal for joint development of interim storage facilities with Chuden in the area planned for siting of the Kaminoseki NPP. Though called “joint development,” Chuden has space to spare in its spent fuel storage capacity, and is not in imminent danger of running out. It is also considering dry storage in the future on the Shimane NPP grounds, which would be more economical and rational. Even if they build interim facilities in Kaminoseki Town, it will take at least 10 years.

The roadmap Kanden announced to Fukui Prefecture (Table 3) in the form of explanatory materials on October 10, 2023 is pie-in-the-sky, because it assumes completion of the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant, which is unrealistic. What should be noted in these explanatory materials is that they say, “To achieve smooth transport of the spent fuel to the interim facilities and, in addition, to enable it to be stored in a highly safe manner not relying on a source of electric power until it can be transported, we are considering creating dry storage facilities on power plant grounds in preparation for future transport from the power plants.” Nishimura Yasutoshi, Japan’s Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry, added his support to this and Governor Sugimoto Tatsuji of Fukui Prefecture also acknowledged it.

Incidentally, there have been moves recently to attract on-site dry storage facilities to Fukui Prefecture. Yamaguchi Jitaro, former mayor of Takahama Town, proposed inviting interim storage facilities in June 2004 and had a resolution passed in the town assembly. He thought that by locating them there it would contribute to regional development. Years later, in December 2020, assembly chairman Takenaka Yoshihiro, referring to the 2004 resolution, stated that he would like to promote on-site dry storage (Mainichi Shimbun, 18 Dec. 2020). In addition, the district chiefs’ association of the Nishiura district of Tsuruga City, near the Tsuruga NPP, sent a written opinion on attracting interim storage facilities to the city and prefectural governments in December 2020 (Mainichi Shimbun, 16 April 2021). Such moves have not altered Fukui Prefecture’s policy of transporting spent fuel outside the prefecture.

Regardless of whether it is on-site or off, there is strong opposition to dry storage, because, as events thus far have indicated, expansion of the storage capacity is an essential requirement for reactor restarts to proceed.

Reactions of Communities in and around Kaminoseki Town

A parliamentary association consisting of assembly members from two cities and four towns around and including Kaminoseki Town, and which is opposed to the planned NPP feels that it is not a matter for the town by itself to decide, but the views of the surrounding municipalities should also be taken into account. They approached each of the cities and towns asking questions of their respective assemblies. The responses of each city and town are presented below (from a report by Nakagawa Takashi, representing the parliamentary association).

Iwakuni City’s mayor: I think considerable anxiety is arising because various procedures are being undertaken with no attempt to gain the understanding of communities including Iwakuni City.

Yanai City’s mayor: I have asked the mayor of Kaminoseki to be cautious and would like to seek an explanation from and have thorough discussions with the government and electric power companies.

Hikari City’s mayor: We will continue to oppose nuclear facilities. We are listening to residents’ views and keeping a careful watch, with safety and security in mind.

Tabuse Town’s mayor: Our town’s image will be diminished, making people less likely to move and settle here. The plan has no merits at this time. Neither the government or nor Chuden. have provided a solid explanation. The heads of the adjoining cities and towns are struggling to cope with it. Regional revitalization measures should be brought up only after safety has been exhaustively discussed. It is extremely regrettable that this was not done first.

Hirao Town’s mayor: We fear this will have a big impact on our town development in the future. It will be a serious problem for local governments and residents in the surrounding area, and measures to promote child-raising, moving and settlement here and education will inevitably be impacted.

Suo-Oshima Town’s mayor: We solicited views widely through public comments and questionnaires, and would like to convey those as our town’s intention.

Mayor Nishi of Kaminoseki Town comments that the government and Chuden should provide explanations addressing these concerns.

Perhaps actions like these in the surrounding area are having an effect. Chuden gained permission from Kaminoseki Town for deforestation as part of a survey, but has not initiated real activities.

Conclusion

Thus far, Japan’s government has not approved of new siting of NPPs under its nuclear recovery policies. It has only approved of the construction of new NPPs to replace existing ones. Although Chuden has revealed parts of its plans, it has stopped short of including dates of construction and start of operations.

An application for approval of construction of the Kaminoseki NPP was submitted to the then Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency in 2009, and after about five inspections had been made, the examination process was discontinued due to the Fukushima nuclear accident. It has not resumed since. After the accident, new regulatory standards were created, so in effect, the application form is being resubmitted.

That construction has not begun even 40 years after the plans first came to light in 1982 speaks to the success of the citizens’ movement that has continued to oppose it on Iwaishima Island. The residents there are also strongly opposed to new interim storage facilities. With this movement active in the town and surrounding municipalities, it will be difficult for Chuden to proceed with its plans.