Two Accidental Exposure Incidents at Fukushima Daiichi

By Ban Hideyuki (CNIC Co-Director)

Two accidents resulting in internal exposures occurred recently at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, where decommissioning work is in progress. The first was on October 25, 2023 at the expanded ALPS treatment facilities. The second was an accident that occurred on December 11 in a building adjoining the operating floor of the Unit 2 reactor.

Internal Exposure of Two Workers at Expanded ALPS Treatment Facilities

Recently expanded Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS) treatment facilities commenced operations from October 24, with pipe cleaning work continuing into the next day. At about 10:30 a.m. on the 25th, contaminated water began spraying from a temporarily installed flexible pipe, hitting two workers. Three more workers were exposed during efforts to clean up the leaked effluent. The cleaning work was being conducted on previously existing pipes connecting the pre-treatment equipment of the newly added ALPS facilities with adsorption towers. Three ALPS systems had been newly added, and the piping in question had been connected to one of them, System B. Carbonates adhere to the inner walls of these pipes, blocking the flow, so these cleaning operations have been conducted once each year since 2022. Nitric acid is poured into the pipes to dissolve the carbonates clogging them up. Carbon dioxide is released in the process, so the amount of nitric acid introduced is adjusted while keeping an eye on the gas pressure. For this work, valves that are normally left open are almost entirely shut off. As a result, the gas pressure rises, and as the carbonate dissolves, the solution shoots violently through the pipes, causing the pipes to jolt. The reason the flexible pipe bucked free was that the position of the attachment securing it was faulty. It is worth noting that no safety evaluation had been performed for this work of shutting off these valves.

In its initial announcement, Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings (TEPCO) said that the amount of effluent that was sprayed was 100 milliliters, but this was quickly corrected to several liters. The main radionuclide released was strontium-90, and the total beta dose was 4.376 billion bequerels per liter.

In its initial announcement, TEPCO also presented a figure with five workers present at the site, but later indicated that nine workers had been there. The nine workers consisted one person in charge of the work, one design engineer and one radiation manager, these three persons being from the original contracting company (Toshiba Energy Systems & Solutions Corp.). There was also one person in charge of work from the subcontractor and no one present from the second-tier subcontractor. There were five workers present from three third-tier subcontracting companies. The first of these latter three companies had three workers present, two of whom (workers A and B) were helping to monitor the receiving tank, and the third (worker E) who was monitoring the chemical solution injection pump. The second company had one (worker C) present, monitoring the receiving tank; and the third company supplied the task leader (worker D), who operated the chemical solution injection pump. The second and third-tier subcontracted workers are thought to have been self-employed individuals. This is a complicated, multi-layered form of employment.

As the two workers (A and B) who were directly caught in the effluent spray were not wearing waterproof anoraks, the surface of their skin became contaminated. Even after efforts were taken to decontaminate their bodies, the level could not be brought down to the standard of 4 Bq/cm2, and they were therefore hospitalized (and released on the 28th). They are said to have suffered no ill effects. It cannot be denied, however, that the accident led to internal exposure as a result of radioactive substances penetrating via the surface of the skin. The three workers (C, D and E) who performed work to clean up the effluent were wearing waterproof anoraks and waterproof slacks. Worker C managed to avoid contamination. Workers D and E were slightly exposed.

Under the Fukushima nuclear power plant decommissioning plan, based on the Nuclear Reactor Regulation Act, wearing anoraks is mandatory during work. Yamanaka Shinsuke, who heads Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA), says they were in violation of the implementation plan. Either the worker in charge from the former contracting company or the radiation manager should have ensured that all present were wearing their anoraks, so why was that not done? Prior to beginning the work, they should have held a meeting. If workers A and B had been directed to wear their anoraks at that stage, it is highly likely that they would have avoided heavy bodily contamination even when sprayed directly by the effluent.

TEPCO employees neither perform onsite work nor go out to check on it. Not even in the report following the accident did they look into why no one had ensured that the workers were wearing their anoraks.

To prevent recurrences, TEPCO says, “In cases where there has been a change in work content, such as when a task is to be performed for the first time or when the work location or procedure are changed, we will be sure to confirm conditions onsite before beginning the work there.” They will also require their primary contractors to do likewise. This means that if it is not a new task and if there are no changes in the work to be performed, it is permissible to skip onsite confirmation. Also, as their way of strengthening safety measures, they say, “For work involving the handling of hazardous substances, we will implement safety measures in the anticipation that these may disperse unexpectedly over a wide area.” They also say they will take other steps such as enhancing their education on protection from radiation.

The NRA, on the other hand, points out that TEPCO “failed to ascertain the risk because it was just a cleaning operation, and had included insufficient safety measures in the work plan,” failing to take sufficient steps to confirm conditions of the work environment and operational system involved.

Worker Exposure Evaluation

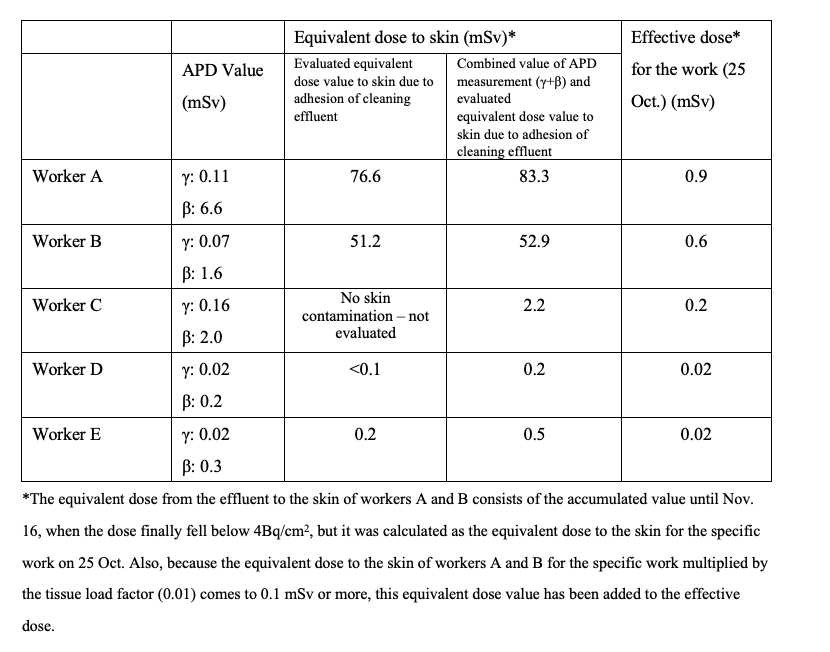

The table shows a radiation dose assessment for the work performed on 25 October (“APD” (Alarm Pocket Dosimeter) in this table refers to a personal electronic dosimeter with an alarm that each worker has).

The exposure doses to the skin of workers A and B are higher by orders of magnitude. The results of their medical examinations found no beta radiation burns.

The APD measurement value for worker C was 2.0 mSv, the second largest beta dose. Worker C was working on a different pipe cleaning line when the accident occurred, and was therefore not present at the location. This may have been because he had been monitoring the receiving tank on the first day.

Bodily Contamination during Work to Improve the Unit 2 Operating Floor Environment

Regarding the accident on 11 December, a nasal smear found contamination of a worker conducting decontamination work on a fence installed to prevent foreign objects from falling into the spent fuel pool. The fence had been removed to a front room adjoining the operating floor. His beta dose was about 1,000 cpm (counts per min.), but his alpha dose was zero. There is a high likelihood that he suffered internal exposure. It is said he was diagnosed by a physician in the emergency medical room at the plant’s entry/exit administration building as having no abnormalities in his physical condition. However, the effects of internal exposure cannot be ascertained during a short diagnostic examination. There has been no word on his follow-up observations.

Note that when workers leave the front room, their anorak, full-face mask and other gear are wiped down to decontaminate them, after which they undergo a smear test to confirm that their contamination is at background level.

After observation during the nasal smear test, this worker cleared the standard level of 4 Bq/cm2 for facial decontamination, and was allowed to depart from the radiation control area.

Regarding the cause, TEPCO said there had been no problems with the full face mask filter or the mask’s pressure release valve, but the mask chin and base of the filter were found to be contaminated. The cause of his bodily contamination was thus surmised to have been that he had failed to loosen the mask’s fastening band sufficiently before removing it and some radioactive residue remaining on it may have stuck to his chin and spread to his nose.

TEPCO says it will take measures to ensure the workers know they should wipe off their mask carefully and loosen the band sufficiently before removing it. In the long term, from January 2024 TEPCO said they would implement an education course using instruction materials that help workers get a clear understanding on how to loosen the face mask band.

There is one point that remains unclear, however: With several thousand people working at the plant every day, was it only these particular workers who were not loosening their face mask bands sufficiently? This accident may have resulted from that lapse combined with a haphazard way of wiping off their masks. Even so, it leaves us wondering if similar accidents haven’t occurred in the past.