Commemorating Nuke Info Tokyo’s 200th edition: Building international solidarity through information sharing

By Caitlin Stronell, NIT editor

On January 13th, I organized an online meeting with previous NIT editors as well as members of the NIT translating team to discuss their thoughts on the roles and impacts of NIT through its history of 200 editions.

Thank you to Ayukawa Yurika (NIT editor from 1988-1995), Philip White (NIT editor from 2004 -2011) and present NIT translators/proofreaders Tony Boys and Patricia Ormsby for sharing their time and experiences. Our discussion brought up a lot of memories of people and events in the anti-nuke movement. There have been many changes since NIT published its first edition in 1987, from the spread of the internet to a triple meltdown at a Japanese nuclear power plant. I hope that this article will give you a glimpse into how NIT has grown and developed along with these changes, and also introduce some of the people behind it.

“Determination” and “support from international readers”

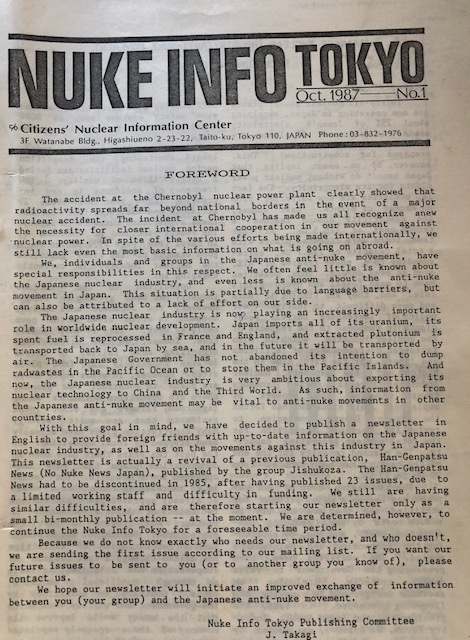

In an article commemorating NIT’s 10th anniversary (NIT No. 61), Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center (CNIC) founder, Dr. Takagi Jinzaburo explained how NIT started: he attended the Anti Atom International Conference in Vienna in 1986 and was shocked at how little was known about Japan’s nuclear industry, and even less about Japan’s anti-nuke movement. Always a strong advocate of international solidarity against the global nuclear industry, Dr. Takagi was determined to publish an English newsletter despite problems of securing financial support and working staff. “Let’s just try 5 or 6 issues and then think again whether to continue” was apparently how NIT started, so he was very pleased that NIT had continued for 10 years, despite these problems persisting. Dr. Takagi also acknowledged in this article that “The greatest reason NIT has managed to survive and enter its second decade is obviously the continuing encouragement and support of international readers.” Now that NIT is in its fourth decade and its 200th edition, it is still determination of the kind Dr. Takagi expressed back in the first edition, as well as the continued support of our readers that is very much the reason we are still here! Dr. Takagi must be very happy and proud of this 200th Edition. Thank you everyone! Some things don’t change.

“Building a nuclear free world with solid data and citizens’ strength”

This is CNIC’s mission statement. The balance between providing accurate scientific information on the dangers of nuclear power in a way that non-experts can also understand, but also including the stories of citizens’ strength is one of the challenges of editing NIT. Alongside straight data on radiation exposure or Japan’s plutonium stockpile etc. and background articles explaining the more obscure aspects of nuclear regulation or the legal system in Japan, right from the first edition, NIT has also included a regular column ‘Who’s Who’ which introduces individual anti-nuke activists in Japan. Since 2004, Philip, the editor at the time, also started including the Group Introduction as a regular column, alternating with ‘Who’s Who.’ These are also popular columns amongst readers, where they can meet the actual citizens and groups which make up the movement.

Another of Philip’s most important contributions was digitalizing old issues of NIT and organizing the English web site. So much information had been compiled over the years, but making it available to the public and, most importantly, the media, proved to be hugely significant when the Fukushima Daiichi triple meltdown occurred in 2011. Timely reporting of what was actually happening in Fukushima was of course essential, and information from independent expert sources such as CNIC was highly sought after. Philip was fielding calls from foreign journalists around the clock, and what proved to be very useful, especially for many of the journalists struggling to understand the complexities of the nuclear industry in Japan for the first time, was the wealth of background information in NIT, accessible from the website. The role of NIT, not just as an accurate reporter and analyzer of current situations, but as an archive, became very apparent.

This was of course made possible by the internet but our discussion then turned to how NIT functioned before digital technology became so widespread.

NIT in the pre-internet era

Yurika, who edited NIT from 1988-1995, recounted a CNIC campaign that amongst activists is somewhat of a legend. According to NIT No. 32, “Akatsuki-maru left the port of Cherbourg (France) around 5:00 am on the morning of November 8 (1992) bound for Japan loaded with 1.5 tons of plutonium.” CNIC joined with many other groups in a global campaign to stop plutonium shipments and the mere mention of the ship’s name Akatsuki-maru still provokes reactions in many of the key campaigners.

Dr. Takagi on hunger strike outside the Science and Technology Agency, in protest against the Akatsuki-maru plutonium shipment (4 January 1993)

Japan’s nuclear fuel cycle policy is the subject of many more recent NIT articles and campaigns, but Akatsuki-maru was the first large-scale international shipment of plutonium reprocessed from commercial nuclear reactor spent fuel and protests against it were fierce and global. There was a loud silence from the Japanese government, citing security concerns as the reason why they were not giving out any information about the shipment.

Under these circumstances, it was vital to get information about the extreme dangers of plutonium and the effects it may have on the countries the shipment was expected to pass by if any unpredictable incident occurred during the shipment. Yurika explained that CNIC information packages, including back issues of NIT with articles explaining the background, were mailed out by post to each of the countries along the 3 likely routes, and thus potentially affected. Dr. Takagi was called to embassies in Tokyo to brief staff about the dangers that Japan was placing their countries in. The Asia-Pacific Forum on Sea Shipments of Japanese Plutonium was also held over three days about a month before the Akatsuki-maru left France. The same issue of NIT (No. 32) contains a full report of the Forum which was attended by large numbers of Embassy staff and the domestic and international press. One of the speakers was the President of Nauru, who protested in strong terms against the plutonium shipment which was “yet another example of the imposition of a nuclear risk on the Pacific peoples without our counsel or consent.” Yurika added that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was caught totally off guard as they couldn’t believe the President of a country would come to Japan at the invitation of an NGO, and after confirming by telephone with CNIC when he was arriving, rushed to the airport with red carpets.

Yurika recalled that, in the end more than 40 countries expressed concern or declared opposition to the plutonium shipments, and when the Akatsuki-maru finally arrived in Japan the Cabinet Secretary had to apologize to all those countries for causing such anxiety. It seems that the government was caught by surprise in more ways than one, and Yurika felt that, although the shipment couldn’t be stopped, this campaign was in many ways a victory because the government realized what citizens are capable of—not only understanding the technicalities of nuclear matters, but also mobilizing this information to gain international support. This meant that information disclosure is essential and authorities couldn’t just operate behind closed doors and assume no one would understand the dangers. The Japanese government has always been sensitive to foreign pressure and this is one of the reasons why international solidarity is so important.

The post-Fukushima era

The paper version of NIT, when volunteers and staff would sit round a table and stick labels on envelopes and then take them all to the post office to send off around the world, was disbanded in 2009 with some regrets, but a realization that the world was moving towards digitalization and that there were lots of cost-saving and time-saving advantages to be had. After that, a pdf version was produced and emailed to readers, as well as, of course being uploaded on the website. With the CNIC office move and a reduction of design staff in 2018, NIT went from the pdf version to html only. There is no doubt that web publication is more flexible, in terms of the length and number of articles as well as the timing. Recently I have been endeavoring to post articles and information as they come to hand rather than waiting for the bi-monthly NIT publication date. I sometimes worry that this flexibility will lead to a kind of disintegration of NIT, but I think the continuation of regular columns such as News Watch and Who’s Who as well as the data and analysis that NIT provides on a regular basis will enable us to keep our identity intact.

As the tenth anniversary of the Fukushima Daiichi meltdowns fast approaches, we are once again reminded that this disaster is very much ongoing. There are so many complex problems, both technical and human, that remain completely unresolved and it is very important that the world doesn’t forget this. This has of course been one of NIT’s major roles and we hope that the information and analysis that we provide on this ongoing disaster will add to the momentum of the global nuclear energy phase-out.

Where to from here?

The role of NIT is “to provide English speaking friends with up-to-date information on the Japanese nuclear industry and the movements against it.” It was both humbling and very inspiring to hear about the ways this role has been performed over 200 editions through different ages and circumstances, and the many people who have been involved in bringing this information to readers.

Going through some of these back issues it struck me that although many things have changed, many things are still the same. The Japanese government still refuses to give up its nuclear fuel cycle policy, although they did decide to decommission the Monju prototype fast breeder reactor, for which the Akatsuki-maru plutonium was bound. At the same time, international solidarity has always played a big part in our victories. For example, the International MOX Assessment, published in 1997 by Dr. Takagi and Mycle Schneider, and one of the reasons they were awarded the Right Livelihood Award, was a major undertaking which involved global collaboration. More recently, as reported in NIT No. 177 , the plutonium conference we held jointly with the Union of Concerned Scientists, in 2017, resulted in CNIC organizing a delegation of bipartisan Japanese lawmakers to visit the US to lobby their American counterparts, as well as the State Department, regarding the US-Japan Nuclear Cooperation Agreement (NIT No. 180). Although this agreement, which allows Japan to reprocess its spent fuel to extract plutonium, was eventually renewed in July 2018, the Japanese government made an official policy statement that it would “secure a balance between demand and supply of plutonium.”* This may seem like a small victory, but it is one that was certainly brought about through international solidarity and one which we will all continue to work on together until the nuclear fuel cycle policy is officially terminated.

Especially this last year, the COVID-19 pandemic has made both the advantages and disadvantages of technology very apparent. While NIT must continue to provide the ‘solid information’ necessary for citizens to build a nuclear-free world, perhaps going forward NIT should look for some add-ons? A greater SNS presence perhaps? This may well help expand our people-to-people connections. As always we look forward to the suggestions and support of our readers. It is with great appreciation and respect for all of the people who have built up NIT over 200 editions that the present team carries the baton forward.

* Japan Atomic Energy Commission: “The Basic Principles on Japan’s Utilization of Plutonium” 31 July 2018