Will TEPCO be Allowed to Restart Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Station Unit 7? Niigata Prefectural Authority’s Attitude Questioned

By Yamaguchi Yukio (CNIC Co-Director)

Is safe management and operation of nuclear power plants possible?

10 years have passed since the severe accident at Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s (TEPCO) Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Station (FDNPS). There is still no end in sight. It is highly questionable whether TEPCO is capable of achieving a complete accident cleanup. (See CNIC Statement).

In addition, two seismometers attached to Unit 3 were still unrepaired at the time of the earthquake on February 13, when a maximum 6+ on the Japanese seismic intensity scale of 7[1] occurred in Fukushima and Miyagi Prefectures. Seismic data was therefore not recorded. This is simply unbelievable. During the several decades it will take to complete the decommissioning work, earthquakes of various sizes are bound to occur. Will it be possible to prevent the collapse of or damage to the nuclear reactors and related facilities? Isn’t the collection of detailed data on earthquakes that the plant is subject to one of the most basic tasks that should be carried out on a regular basis?

Meanwhile, a series of new incidents have come to light that cast doubt on TEPCO’s capability, credibility and degree of sincerity about getting the job done properly. The situation has developed into a serious predicament in which the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA, both the agency and its associated committee) is suspected to have played a role.

The ID misuse problem that occurred on September 20 is a serious incident that reflects on nuclear security and nuclear protection at Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Station (KKNPS) Unit 7. TEPCO reported the accident to the NRA on September 21, and the agency began an on-site investigation in October. The agency reported the accident to the NRA Committee at the end of January 2021. Why did NRA keep the incident hidden for almost four months? On September 17, a review meeting of the NRA Committee approved the re-revised draft of TEPCO’s “safety regulations.” On the 23rd, Unit 7 received approval for the entire assessment of the reactor at a regular meeting of the NRA Committee. Was the NRA really unaware of the ID misuse incident in the meantime? There remains the strong suspicion that NRA may have taken the restart Unit 7 into consideration.

However, the matter does not end there. In January 2018, a failure was discovered in a counterterrorism intrusion detection system, with a total of 15 breakdowns being discovered later, between March 2020 and February 2021. At 10 of these sites, insufficient measures by TEPCO resulted in the inability to detect intrusions for 30 days or more.

The NRA, stating, “The organizational management function of Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Station has deteriorated, and the effectiveness of protective measures have not been appropriately comprehended for some considerable length of time. This is a potentially a serious situation in terms of the physical protection of nuclear materials,” handed out a tentative “red” evaluation, the most serious in the 4-tier evaluation system, on March 16, which was confirmed on the 18th. In the case of misuse of the ID card, the assessment was “white,” the second lowest category.

Meanwhile, TEPCO announced that it planned to restart the reactor in June 2021 and that it had completed all safety work on January 13. However, the company revised the announcement on the 27th, stating that a part of the construction had not yet been completed. TEPCO had already started holding explanatory meetings with local residents from the 25th. Further uncompleted construction works were later discovered, and on March 3, a totally absurd fourth announcement on uncompleted construction work was made.

Seen this way, we have to assume that TEPCO, the power company directly involved in the severe nuclear accident at FDNPS, has neither the capability nor the credibility required to operate nuclear power plants, nor has it been serious about managing nuclear power plants properly. For Japan’s largest electric power company, with the largest number of elite nuclear engineers, if this is the case, then we have little option but to judge that electric power companies are inherently incapable of the safe management and operation of nuclear power plants. It is also highly questionable whether the Nuclear Regulation Authority and its associated committee, which overlooked the current situation, are capable of enforcing nuclear safety regulations.

It is not without reason that we need to scrutinize TEPCO with a particularly harsh eye. This is not the first time TEPCO has been caught committing grave misconduct. In August 2002, a shocking incident came to light. The “TEPCO coverups” involved concealment and deceit concerning numerous fissures in pipes, shrouds and other structures. The investigation covered reactors at TEPCO’s FDNPS, Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Station and KKNPS. Damage such as fissures remained unrepaired (at 8 reactors) and deceitfully concealed (at 13 reactors). These problems were revealed by a whistleblower, a former employee of a GE subsidiary who was in charge of the inspections. As a result, the TEPCO chairman, corporate advisers, president, and others took responsibility by resigning, followed by the installation of Katsumata Tsunehisa as TEPCO Chairman.[2] Nine years later, however, his administration was involved in the severe accident at the FDNPS. It was probably inevitable. This brings to mind the judgement of the chairman of the National Diet of Japan Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission (NAIIC) on the Accident: “regulatory capture.”

The coverup incident acted as a trigger for the discovery of similar coverups at other companies, including Chubu Electric Power Co., Tohoku Electric Power Co., Japan Atomic Power Co., and Chugoku Electric Power Co. As the investigation progressed, it was discovered that data had been falsified during a regular inspection of the FDNPS Unit 1 containment vessel, and an administrative order was issued to shut down the reactor for one year. This was the first severe punishment meted out in the history of Japanese nuclear power plants.

Who decides?

The nuclear village, led by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the power industry, has made an unusual effort to get TEPCO’s KKNPS Unit 7 restarted in June 2021. As we have already seen, it may be inferred that the work of the NRA and its committee has been pushed forward with this goal in mind. The government and electric power companies believe that if the reactor receives approval as a result of NRA’s safety assessment, the reactor can be restarted if the power company and local communities reach agreement, and that scenario is generally accepted. Strong pressure from the Niigata Prefectural Assembly and “local people” who support the restart has been reported. “Local people” in this context means the municipalities where nuclear power plant is sited and the prefectural governor. The scenario is that the governor, after reaching an agreement with the prefectural assembly, will then officially approve the restart of the reactor.

The “Agreement on Securing the Safety of Areas Surrounding Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Station”, concluded in 1983 and partially revised several times, involves three parties, namely, Niigata Prefecture, Kashiwazaki City and Kariwa Village, and Tokyo Electric Power Company. Other municipalities are not parties to the agreement.

When the severe accident at FDNPS occurred, Unit 4 was, for a time, considered to pose the greatest danger. The level of cooling water in the spent fuel pool was falling, the decay heat could not be ignored, and there was the possibility that a large amount of radioactive material could be released into the environment. The impact of this could have extended more than 250 kilometers. By sheer coincidence, however, the sloppy nature of the construction turned out to be a blessing in disguise, and a huge catastrophe was averted.

As the movement to restart KKNPS Unit 7 heated up, councilors from all eight municipalities within the 5 to 30 kilometer radius (UPZ) of the plant, the evacuation preparation zone, gathered to make an all-party effort in August 2020 for recognition of the “right to prior consent.” This follows the system initiated by municipalities in Ibaraki Prefecture, which hosts Tokai Daini Nuclear Power Plant. Approval granted as a result of the NRA assessment does not guarantee safety, which has been made clear by the NRA itself. Protagonist politicians often assert that security is guaranteed by “the world’s strictest standards” but this is a complete lie.

Taking into account the current circumstances, the Niigata prefectural government has been forced to shoulder the burden of the question of who is going to make the decision to restart KKNPS.

The question of who is responsible does not exist in the conventional system. It is literally an irresponsible system. Throughout the last 10 years, it has become clear that neither TEPCO nor the national government nor Fukushima Prefecture have any intention of taking responsibility for the severe Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. Naturally, it will therefore be concluded that no one has the qualifications or eligibility to make the decision to restart the reactor.

At the time of 3/11

There is a tanka poem that reads: “Evacuating my hometown with anger, despite having done nothing wrong.” The author expresses uncontrollable anger directed at TEPCO for bringing about the accident, the prefectural governor who accepted the nuclear power plant, and Japan for promoting nuclear power. All the people involved continued to say over and over again that Japan’s nuclear power plants are safe and that accidents will not occur. Those who continued to say so bear responsibility. Ordinary citizens feel that nuclear power plants are “difficult to understand” and should be left to competent experts and organizations. The experts and organizations entrusted with this responsibility have been found, after all, to be irresponsible and incapable.

In retrospect, however, I suspect that each and every one of us was involved in the “wrong” that accepted nuclear power. The anger expressed in the poem may also have been directed at the poet him/herself.

Nuclear accidents are possible. The next time it happens, it may not stop at the scale of the severe accident at FDNPS. I believe it is precisely each and every person who might become a victim that has the qualification and the right to decide whether or not to restart the nuclear reactor. I’m not talking about mayors or prefectural assemblies. Nor the governor. I mean everyone. I don’t think there is any other way to go about it.

The Niigata Method and its Future

The Niigata prefectural government has its own system for examining nuclear power plant safety. Or perhaps I should say it had one.

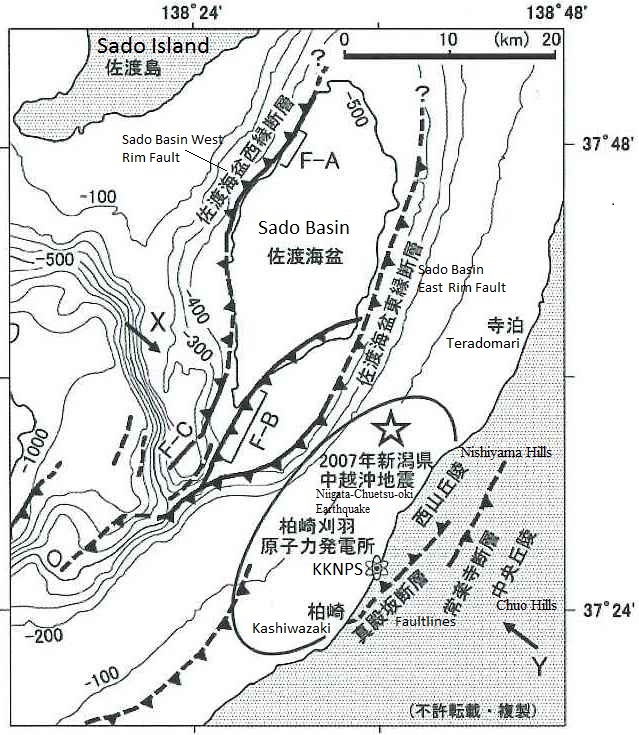

Triggered by the 2002 “TEPCO coverups”, the Technical Committee into Safety Management of Nuclear Power Plants in Niigata Prefecture was launched in February 2003. Later, in 2008, two subcommittees the Subcommittee into Equipment Integrity, Earthquake Resistance and Safety (eight members) and the Subcommittee into Earthquake and Ground Condition (six members) were formed. The reason for the establishment of these committees was the world’s first nuclear power plant to be damaged by an earthquake. At the time of the Niigata Chuetsu Offshore Earthquake (M6.8) in July 2007, all KKNPS reactors, including those undergoing periodic inspections, were shut down (Units 3, 4, and 7 were in operation, Units 1, 5, and 6 were undergoing regular inspections, and Unit 2 was in the process of starting up). In the Technical Committee, consisting of 14 or 15 members, discussions were not getting in too deep. A forum for deepening substantive discussions was needed.

After all, TEPCO’s KKNPS, with a total of seven units and a generating capacity of 8.212 million kilowatts, is the world’s largest nuclear power plant. The foundation on which it was built is soft ground, “like tofu.” Moreover, Niigata Prefecture is well known for its frequent large earthquakes, including the Niigata Earthquake (M7.5, 2004), the Niigata Chuetsu Earthquake (M6.8, 2004), and the Niigata Chuetsu Offshore Earthquake (M6.8, 2007).

A major feature of the Niigata method is that it created subcommittees that include not only nuclear power protagonists but also a number of critics, who engage in heated argument. I wonder if there are any other committees or councils like this in Japan, let alone in other countries. Most of the members of the committees are from the administration and are chosen on the assumption that they have a good idea about the compromises that will be reached in the discussions. In particular, councils and committees set up by central government ministries and agencies appear to be engaged in democratic deliberations, but the contents are not necessarily so. The system is designed to enable the will of the state to be realized.

The two subcommittees met frequently, at a pace of one or two meetings a month. Everything was completely open to the public, not just to the people of the prefecture. The results of the discussions were reported to the Technical Committee, the parent committee, by the respective chairmen. The two committees held repeated discussions, but there remained quite a number of points on which the committee members could not agree. These nine items were discussed by the Technical Committee, but conclusions were not reached. With a certain amount of homework still remaining, the restart of Unit 7 was approved by the committee at the discretion of the chairperson.

Allow me to list some of the most important points on which opinions differed.

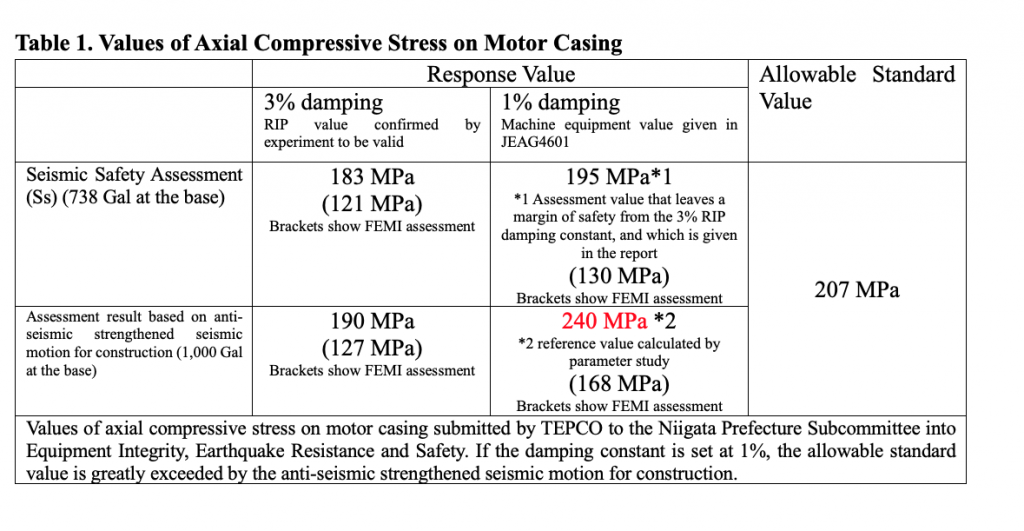

– Regarding equipment integrity and seismic safety: Was there slight plastic deformation in the equipment due to the earthquake, and does this affect the integrity of the equipment? This discussion ended without agreement. In particular, there remained strong suspicions right up to the end on whether damage by an earthquake to the motor casing of Unit 7 could be avoided. The danger of exceeding the allowable standard value of axial compressive stress is shown in Table 1.

The reference value will be exceeded if the response value is calculated with a damping constant of 1% when the casing is shaken and damped by an earthquake. The GE design guideline indicates 1%. Despite knowing this, TEPCO is suspected of having calculated the rate at 3%.

– Regarding earthquakes and geological features: Assessing the design basis earthquake ground motion (DBEGM) for the F-B fault, considered to have caused the Chuetsu Offshore Earthquake, it appears to be underestimated. Essentially, the east rim fault of the Sado Basin, which is over 30 kilometers long, should be considered, thus assuming an earthquake of M7.5. Opinions remained divided on the pros and cons of this. It also proved impossible to clarify why the four corners of buildings were unevenly displaced.

When Unit 7 resumed operation in December 2009, in defiance of opposition from many residents of the prefecture, the Technical Committee assigned the subcommittees four homework items.

- Consideration of the topological formation process and geological structure in Kashiwazaki-Kariwa area

- Consideration of displacements of buildings

- Consideration of activity of the Nagaoka plain west rim fault

- Consideration of seismic activity based on the Niigata Chuetsu Offshore Earthquake

These are ongoing challenges. In particular, since 2. is related to the stability of the ground, it cannot be resolved unless 1. is correctly clarified.

Following the Great East Japan Earthquake

On March 11, 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake (M9.0) occurred just as the Subcommittee into Earthquake and Ground Condition was meeting for the 25th time in Niigata City. The committee adjourned, was held twice up to September of that year, and subsequently discontinued. The Subcommittee into Equipment Integrity, Earthquake Resistance and Safety was held for the 51st time on March 8, just a few days before the earthquake struck.

The Niigata prefectural authorities, under the supervision of Governor Izumida, decided to start work on a verification of the Fukushima nuclear accident in the Technical Committee with the subcommittees remaining adjourned. Having expanded its membership, the Technical Committee aimed to contribute to the safety of KKNPS. Between April 2013 and August 2020, six priority issues were identified, core members were appointed for each issue, and discussions were held in closed session. With the exception of Task 1, “Impacts on important equipment due to seismic motion,” the work for Tasks 2 to 6 was completed in four to seven meetings by February 2016. Task 1 required 14 meetings, up to August 2020, for completion. Former NAIIC committee member Tanaka Mitsuhiko served as a core member.[3]

Governor Yoneyama, who took over from Governor Izumida, established a “Three verifications and verification system” and a “Verification Supervisory Committee.” The “Three” consist of the “causes of the accident” (handled by the Technical Committee established in 2003), the Daily Life and Health Committee (2017), and the Evacuation Committee (2017). At the time of its establishment, the Verification Supervisory Committee (Chairperson Ikeuchi Satoru) was charged with overseeing these three verification committees, and the governor promised that discussions on the KKNPS restart would not begin until the work of these committees had been completed. The current Governor Hanazumi was also elected with this pledge as part of his election platform.

On the other hand, I have already mentioned the efforts of stakeholders to realize a “Restart of KKNPS Unit 7 in June 2021.” It seems that because of this, Task 1 was rushed forward from sometime part way through the discussions. It may be inferred that the prefectural government’s nuclear safety division changed its stance to head in the direction of a restart of operations in June. On October 25, 2020, the chairperson of the Technical Committee submitted the “Accident Verification Report” not to Chairperson Ikeuchi, but to Governor Hanazumi. What does the fact that it was Governor Hanazumi that received the report tell us?

There is one worrying issue about the future of the Niigata system. The prefectural authorities refused to reappoint two people who had been active members of the Technical Committee for many years and who had also participated in subcommittee discussions with great dedication. The reason given for the refusal of reappointment in April was age. Since the safety of KKNPS was not the basis for the arguments in the Accident Verification Report, how can future discussions be pushed forward? At the very least, there will be a lack of continuity of discussion. This can only be seen as a change from the prefectural authority’s previously cautious stance on the restart of Unit 7 toward an early restart.

Now that incidents have occurred that make TEPCO look highly suspicious as a qualified operator of nuclear power plants, every citizen and resident is faced with the question of whether or not to permit the existence of nuclear power plants. On March 6, the Association for the People of the Prefecture to Decide on the Restart of the Nuclear Power Plant was founded in Niigata City, and a petition campaign launched to collect signatures from all over the prefecture. This is a promising new movement.

[1] This seismic scale, known as ‘Shindo’ goes from 1 to 7, but 5 and 6 have an upper and lower level.

[2] For details see CNIC Ed., “Verification: The TEPCO Coverups”, Iwanami Pamphlet No.582, December 2002 (in Japanese).

[3] For detailed background, see the March 2021 issue of Iwanami’s “Kagaku” (“Science”) and the materials of CNIC’s 5th Online Seminar to Commemorate the 45th Anniversary of the Founding of CNIC, March 10, 2021 (in Japanese)