Report on US Trip—America’s Uranium Development and Japan’s Uranium Garbage (Part 2)

By Matsukubo Hajime (CNIC)

(See Part 1 at cnic.jp/english/?p=6119)

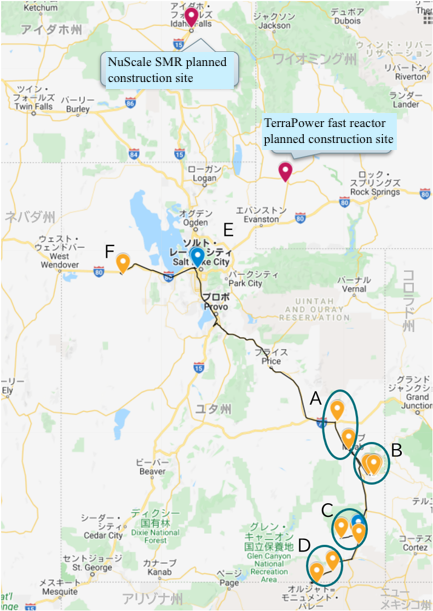

April 3, To the Former Mill Grounds of Mexican Hat

After leaving Moab, we headed south in earnest, staying the night in a small town called Bluff. The next morning, we ate fried bread at a Native American restaurant near the hotel.

Fried bread could be called Native Americans’ “soul food,” but it has a troubled background. In the mid-19th century, America’s indigenous tribes in all areas were forcibly relocated and cut off from their traditional lifestyles. After that, because they were unable to obtain beans and other staple foods that they had been growing prior to then, they began eating fried bread, which they could produce using wheat flour, lard and other cheap ingredients the US government distributed to them. In other words, this was a dietary habit they were forced to adopt to survive. The fried bread we ate was similarly necessary to us, but obviously high in calories and fats. That may be the reason for the high obesity rate among Native Americans (the ratio of their population with a BMI of 30 or more is 42.9%), and their shorter average lifespan compared to other ethnicities.

After breakfast, we visited the Mexican Hat disposal site, located near the distinctive balanced rock feature called “Mexican Hat.” This disposal site, right next to the main highway, was the site of the former Mexican Hat Uranium Mill, that operated during the 1950s and 60s. The debris from that and rubble from demolished buildings constructed using the debris (including a school), along with debris from the Monument Valley Uranium Mill nearby, have been disposed of there. There were no surveillance cameras or anything similar, but barbed wire and other barriers had been placed there, and signs had been posted here and there stating that this was a radioactive waste disposal site under the management of the US Department of Energy (the air dose rate was on the order of 0.15μSv/h).

After that, we went to Monument Valley, a tourist attraction that gives the strongest “American west” impression. Even here scars from uranium mining remain. Monument Valley is a broad expanse within the Navaho reservation, with gigantic craggy buttes in the midst of a deep red desert. We spoke with a woman living in Monument Valley, who told us that none of the former uranium mines were being managed properly and her grandfather suffered damage to his health from radioactive exposure. (He is receiving compensation from the US government). Also, this is an area which receives almost no rain, so water is a precious resource here, but it has been contaminated as the result of uranium mining and other activities. In some places the water is unfit for agriculture or livestock, so to make a living, it seems they have had to set up souvenir shops for the tourists who visit Monument Valley.

April 4, To White Mesa

The next day, we first visited Michael Badback, who lives on the Ute Mountain Ute tribe’s White Mesa reservation, located 8.5 kilometers south of the White Mesa Mill. Badback has for many years expressed concerns over the White Mesa Mill.

The biggest concern among the residents is water issues. That is because one of the mill’s slag ponds is already known to be leaking water. There is concern that the contaminated water could reach the Navajo Aquifer, from which drinking water is drawn. Moreover, he related to us that foul smells emanate from the plant depending on the direction the wind blows, and people worry that they may suffer health effects from these fumes.

We next visited Energy Fuels Inc.’s White Mesa Mill. We found out later that Curtis Moore, who came out to meet us this time, had flown out for us in his private jet (!) from the company’s headquarters in Colorado.

We received an orientation on the White Mesa Mill, which had started out processing uranium and vanadium, and the rare-earth metal refining methods it was currently focusing its efforts on, and we were then shown around the facilities. Started up in the 1980s, aging parts of the operating plant stood out, but as it was the only uranium mill still running in all of the US, the employees were said to be proud of it. Photographs were not allowed to be taken inside the facilities, but the highest dose rate in the areas we were guided through was about 3μSv/h. According to Energy Fuels’ explanation, the groundwater in the Navajo Aquifer moves at a rate of only a few meters a year, so any impact on the White Mesa reservation from the slag pond leak would only occur in the distant future.

After observing the White Mesa Mill, we participated in a tour arranged by Tim Peterson of Grand Canyon Trust run by the local NPO EcoFlight, which takes tourists on flights on small aircraft around the area, and flew over the White Mesa Mill. When we asked about the cost of the flight, we learned EcoFlight was covering it themselves.

April 5, Bear’s Ears National Monument and Uranium

On April 5, we visited part of Bear’s Ears National Monument, guided by Tim Peterson. This national monument was established in December 2016 in the final days of the Obama administration as a nature and antiquities reserve in southeastern Utah. Within its 5,500 square kilometer area, sites sacred to the indigenous Americans, various ruins, and the lovely natural environment are protected. Deep underground, however, are natural resources, including a uranium vein, and when Trump assumed office, the area of the monument was shrunk by 85%. When Biden assumed office, though, it was restored to its original size. Note that Energy Fuels played a big role in these wranglings, because the White Mesa Mill is located adjacent to the monument and could be subject to environmental reviews, and furthermore, they pressured the Trump administration to reduce the size of the area because they had uranium mining interests within its boundaries.

In the national monument, we first visited a uranium mine with the slangy name of “Easy Peasy Mine.” Exploratory drilling was conducted at the mine in 2018, when the monument was in its minimized state, extracting about 30 tons of uranium ore, but as the price of uranium fell, the drilling ceased. Since then, with the monument restored, mining operations have been suspended.

With almost no differences in the surrounding scenery to tip one off, the mine came into view suddenly with no signs posted to warn people of high levels of radiation. Several pieces of mining equipment had been left sitting outside, with no sign of anyone managing them. There was a pile of rock debris which appeared to have been discarded there when the road was built, and when we measured the dose rate there, it came to 1μSv/h. Since we’d come all the way out, we went ahead and followed the roadway into a tunnel and found the air dose rate there to be about 2 to 3μSv/h.

After that, we went to the base of the twin buttes from which the name “Bear’s Ears” was derived. They are a sacred site to the indigenous people, and we enjoyed the spectacular scenery, although we were really only able to get a glimpse of this vast national monument.

April 6, Straight Back to Salt Lake City

The next day, we spent the morning talking with students of the Traveling School (a curriculum offered by a non-profit organization, in which female high school students from all across the US participate, traveling around together for three months to learn about various social issues) and exchanging views with local newspaper reporters before returning to Salt Lake City (about 500 kilometers away).

April 7, A Hearing with Utah State’s Regulators and Antibody Testing

Regulatory oversight of the White Mesa Mill is provided by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and the Division of Waste Management & Radiation Control under Utah’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). We had a hearing with them on regulation of the White Mesa Mill and the issue of importation of radioactive substances by the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA).

From the standpoint of the regulatory agencies, no notable contamination has been seen to arise from the White Mesa Mill’s operations, and since the prevailing winds at the mill are from south to north, there is thought to have been no big impact on the reservation to the south of it. Regarding the foul smells, they explained that those must have arisen from a sewage treatment facility located on the reservation. (Note that when we visited the reservation, we briefly stopped by that sewage treatment facility, and there were no notable odors.)

There was one other place, EnergySolutions, that we had wanted to visit after the hearing (it oversees a low-level radioactive waste disposal site in Utah for large-scale metal recycling from a decommissioned reactor in Tennessee) but we had received absolutely no reply from them. When we mentioned this to the Utah State regulator representatives, they were kind enough to take us out to see the site.

Also, since we were returning to Japan on the ninth, we went that day to Walgreens (a pharmacy store chain) to undergo drive-thru antibody testing. When you make a reservation on the Net and go to the drive-thru window, you are handed an antibody test kit of the type that requires use of a cotton swab to collect a sample from the back of your nose, so that is what we did. The whole procedure was completed with us sitting in our car. America, it seems, really is a motorized society.

April 8, To the Clive Disposal Site

In the morning we visited the DEQ offices again and were transferred to a state government vehicle (Jeep Wrangler) to head out to the Clive Disposal Site, located about an hour and a half west of Salt Lake City.

The Clive Disposal Site is one of four low-level radioactive waste disposal sites in the US, handling only Class A items (equivalent to Japan’s L3 designation). Currently, considerations are said to be underway for disposal of depleted uranium (which is already being managed at the facility).

The wastes are being disposed of at the site of a former Air Force bombing range (which still has craters from the bombing practice). Clive Disposal Site staff showed us around parts of the site outside the radiation control areas. What amazed us was that large equipment items like steam generators were being left out in the open. We were told that these would be buried in the future. EnergySolutions is selling recycled metals from large equipment, and when we mentioned that Japan was eager to get involved with that, the staff member showing us around remarked, “This stuff is nothing but useless junk. What do they intend to do with it?” That made quite an impression on us.

Thoughts on the Trip

What was very impressive to us on this trip was the laxity we witnessed in the management of radioactive wastes. The air dose rates in places where disposal had been completed were not at concerning levels, but despite extremely high air dose rates at facilities in operation, abandoned mines and other places, no efforts at all were being made to manage them. It is possible that there are philosophical differences between Japan and the US regarding safety. In any event, we managed to fulfill the purpose of our trip, which was to get a glimpse of the reality of what is taking place in the US with its nuclear regulations that are said to be “rational.”